In a brief but wide-ranging interview with @ THIS STAGE magazine in September, 2016, just prior to the opening of Barbecue at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles, playwright Robert O’Hara aired his views on “conventional” theater, racism, TV reality shows, the general concept of artistic realism, Hollywood and the notion of American exceptionalism. That this gay black author looks at all of these with a jaundiced eye should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with his earlier work, but the arrival of Barbecue on the San Francisco Playhouse stage provides an excellent opportunity to judge how his forcefully expressed positions integrate in a very dark social satire.

Act 1 is divided into two extended scenes. In the first, O’Hara transports us to a rundown city park somewhere in middle America (nicely rendered by Scenic Designer Bill English), where the barbecue from which the play takes its name, takes place. There’s a realistic-looking grill on a pedestal and some desultory miming with tongs during the performance, but no actual food is ever present. Instead, we get razor-sharp volleys of dialogue among the O’Mallery clan as they await the arrival of an absent member named Barbara (Susi Damilano). Soon, it becomes clear that this isn’t an ordinary beer and burger family outing. Despite reservations by some, the majority, led by strong-willed Lillie Anne (Anne Darragh), decides that with her drug and alcohol dependency out of control, Barbara must be pressured into entering a rehabilitation center—in Alaska, of all places!

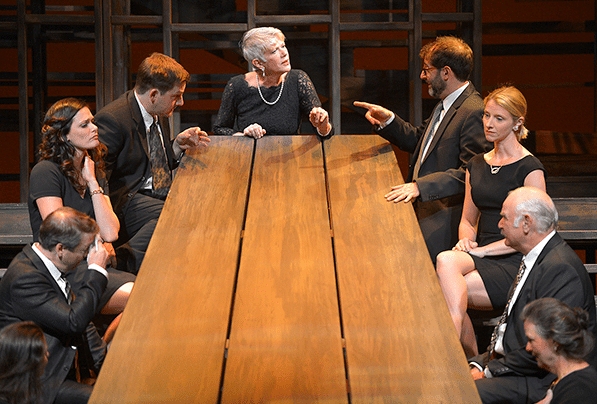

If these were normal people acting under normal circumstances, this would seem to be a perfectly logical response. But the O’Mallery family is anything but normal. They’re archetypal trailer trash, and every last one of them has some kind of substance addiction that would qualify for rehab. This glaring contradiction is the basis for most of the comedy that surrounds their arguments. The result is absurd black satire at its best, beautifully performed by a talented acting ensemble.

After Barbara’s entry in the final minutes of the scene, O’Hara throws us a curve that displays his disdain for conventional play structure. With slight adjustments, the same characters are onstage—wearing the same clothes, answering to the same names, disputing the same issues—only this time they’re African-American and Barbara is being played by Margo Hall, the esteemed black actress who also directs the show. Their chatter is no longer the country-style locutions of white trash; it’s the jivey street jargon of the black community.

At first, the repetition, odd though it is, has its own rewards in the actors’ energy and colorfully expressed dialogue. As it dragged on over familiar territory, however, I found myself wondering about the playwright’s objective. Was he asking his viewers to compare the impact of the two versions? Was he making a point about African-American and white families facing similar problems? Or, was he simply solidifying his reputation as an iconoclast who refuses to be constrained by the generally accepted rules of the game?

Act 2 supplies the answer, though many may find it unconvincing. I won’t offer any details, but what I can say is that the substance and style are completely different—which accords with the author’s expressed desire to be consistently inconsistent as he reflects on a world in chaos. In that respect, at least, he is a worthy successor to the absurdist playwrights of the last century. It remains to be said that Act 2, which replaces black comedy with a heavy burden of personal philosophizing, is not nearly as entertaining as what preceded it, even when the repetition is factored in.

Returning to the interview in L.A. which began this review, when O’Hara was asked what he would like the Geffen audiences to take away from performances of Barbecue, his reply was that he wants them to “laugh until they choke.”

I am tempted to ask, “Then what?”

NOW PLAYING: Barbecue runs through November 11 at the San Francisco Playhouse, 450 Post St., San Francisco; 415/677-9596; sfplayhouse.org.