By David Templeton

It’s three days after the Fourth of July, and the pre-game audience at San Francisco’s AT&T Park is being treated to a voice-over description of the safety procedures should an earthquake or hurricane hit the waterfront baseball stadium. The massive jumbotron flashes a constant barrage of images, announcements, reminders and facts. A tech crew hustles about, assembling various pieces of audio and video equipment while thousands of loud, excited, snack-bearing people fill the vast rows of seats.

Singer/actor Phillip Percy Williams—just moments after doing a quick microphone check at the edge of the baseball diamond, and after a long traffic-snaggled drive from Marin—is valiantly ignoring all of that, purposefully avoiding glancing up at the crowd, and otherwise working hard to stay calm.

After all, Williams has a job to do, and it’s an important one. In just three or four minutes, he’ll be stepping out onto the impeccably groomed baseball field and taking his place—roughly halfway between home plate and the pitcher’s mound—to sing the national anthem. It’s an iconic and surprisingly weighty little piece of modern American culture, the singing of the anthem, both celebrated and taken-for-granted, and occasionally hotly debated. Williams is about to do it before an estimated crowd of 40,000 people, including several friends and colleagues from the Bay Area theater community and his job at the Mt. Tam Orthopedics and Spine Center, along with the entire San Francisco Giants and Miami Marlins baseball teams.

“This is something that’s been on my bucket list for a while,” he calmly but happily notes, cautiously allowing himself to wave at a few thumbs-upping friends who’ve just made their presence known up in the seats. For additional support, his husband Mike and his mother-in-law Karol are nearby, ready to offer support, administer hugs and join Williams in prayer just before taking the field.

Being asked to sing the anthem at a Major League Baseball game, notes Williams, is a very big thing.

“It’s just one of those experiences,” he says, “that, as a singer, you always know is out there as a possible thing to do, if you are ever lucky enough to be asked to do it. And when it happens, it just seems so surreal you almost can’t believe you’re doing it.”

Williams is waiting near the audio station, directly in front of the media dugout, which is adjacent to the visiting team’s dugout. Hovering helpfully nearby is Amanda Suzuki, from the Marketing and Entertainment department of the San Francisco Giants. The main contact for all visiting performers selected to sing the national anthem during Giants’ home games, Suzuki coordinates those performers—one for every home game, including pre-season and post-season games. She is good at what she does, juggling complex logistics with a bit of confidence-boosting cheerleading and on-the-spot relaxation therapy.

“If I could sing, this would be on my bucket list, too,” she tells Williams, generously adding, “But I can’t sing—so it’s a really good thing that you can.”

Yes he can. Originally from Mobile, Alabama, Williams worked for several years as a singer with Carnival Cruise Line, and spent more than 10 years as part of the cast of San Francisco’s Beach Blanket Babylon. Currently, he works as MRI Liaison at the Spine Center, a flexible “day job” that allows him to pursue an array of musical and theatrical projects. Williams performs weekly at San Rafael Joe’s in downtown San Rafael, with the Percy Williams Trio. In recent years, he’s been appearing almost constantly on stage in plays and musicals, and in 2014, he won the San Francisco Bay Area Theater Critics Circle award for Principal Actor in a Musical, for his role in Return to the Forbidden Planet, produced by Curtain Theater and Marin Onstage. Most recently, he played Mrs. White in Clue: The Musical, at Napa’s Lucky Penny Community Arts Center, where he will be appearing again this September in Chicago. But first, there’s a certain song to sing.

“Let’s go over your introduction,” Suzuki tells Williams, showing him her clipboard with the words about to be spoken by Giants announcer Renel Brooks-Moon. Williams reads through it and nods. “In just a minute,” Suzuki says, “we’ll walk out and get in place.” She points to where a monitor and microphone are waiting for him. The video and audio crews are already getting into position. “The camera will be on you as you walk out and get into position, so feel free to wave, smile, whatever you’re comfortable with. And have fun.”

“That’s good,” Williams says, taking a deep breath. “‘Have fun’ is good.”

On the P.A. system, Brooks-Moon’s recognizable voice has just run through another series of reminders, and concludes with, “And now, sit back, get ready for the Giants, and enjoy the game!”

“OK! Ready?” asks Suzuki. “Let’s go.”

Williams is led out onto the field, where he is given the microphone, and told to wait for his cue. Standing in the shadowy late-afternoon light, he finally allows himself to look up and around, bows his head briefly, takes another breath and waits.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” comes Brooks-Moon’s voice again, “please remove your hats, as we honor America with our national anthem. Performing the ‘[The] Star-Spangled Banner,’ please welcome Bay Area performer Phillip Percy Williams.”

Williams waits until the applause has just begun to fade, and then begins.

Williams’ performance, done a cappella, is graceful and moving, hitting all of the marks and nailing the high note on “land of the free” with a soaring falsetto that brings spontaneous cheers from the crowd—a huge assemblage of human beings that Williams will later note is easily the largest audience he’s ever had in his life.

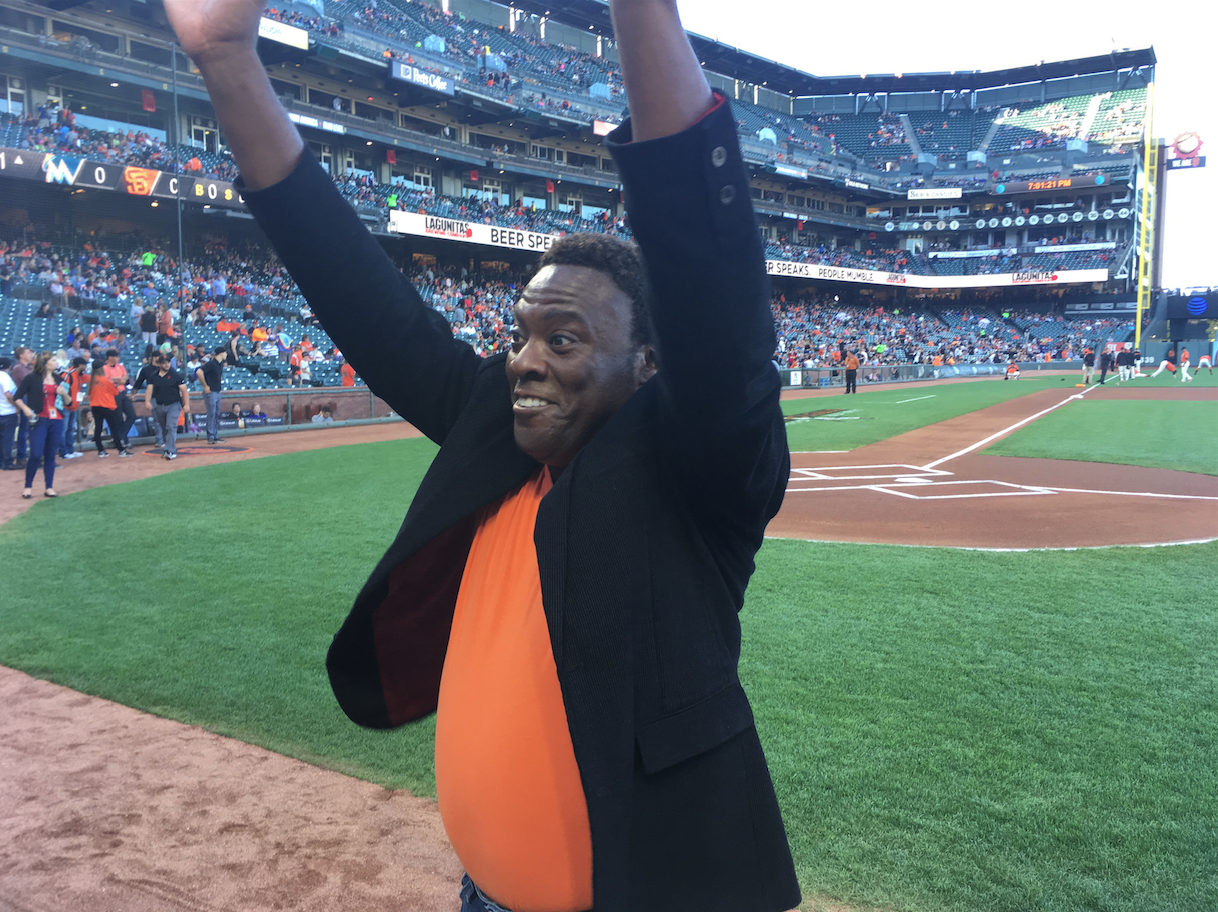

As he walks back to where Mike and Karol are waiting with enormous hugs, Williams acknowledges the applause, finally allowing himself to show his emotions with a joyful laugh and a massive grin that is part, “I’m glad that’s over” and part, “I can’t believe that just happened!”

Suzuki offers her farewells, makes sure Williams and his group have their tickets for the game, and departs. Out on the field, the sound equipment is quickly cleared, the ceremonial first pitch is tossed, the Giants and the Marlins trot one-by-one out onto the field and the game begins. On his way up into the seats, Williams is stopped every few feet, greeted over and over by dozens of new fans and a few old friends, all stepping over from their own seats to shake his hand, offer high-fives, lean in for an earnest ‘thank you’ and generally share their appreciation of his performance.

“I feel like it’s still happening,” Williams says with a sigh, after settling into his seat. “I think it might take me a while to calm down. But, you know, I feel pretty good. I’m really happy.

“That said,” he adds, with a laugh, “I might not be able to eat again for days.”

The national anthem has not always been a part of Major League Baseball games. For that matter, the song known to many as “The Star-Spangled Banner”—and the melody that the lyrics are sung to—have not always been our national anthem. The words, of course, originated as a poem by lawyer Francis Scott Key, reflecting on his observations of the British attack on Fort McHenry in Maryland during the War of 1812. Key saw that the flag flying over the fort was left surprisingly intact the next morning, despite incessant artillery rained down on the fort through the night.

Though some criticize the American national anthem for being a glorification of war, a careful reading of the text reveals it more accurately to be a celebration of the survival of war—and one of the few national anthems of any country that is focused on the dangerous adventures of an inanimate object. Beyond that, the most frequent criticism of the American national anthem is that it is much too hard to sing. The irony of this is that the melody of the anthem was never intended for professional vocalists, but was specifically composed to be sung by deeply inebriated amateur musicians.

The Anacreontic Society was an 18th century English men’s club devoted to, and named for, the ancient Greek poet and celebrated inebriate Anacreon. The club’s anthem, “The Anacreontic Song,” set to a tune composed by John Stafford Smith, is a celebration of music, singing and the consumption of wine. The tune became fairly well-known outside of the exclusive club—which faded away in the 1790s—and was often used as the melody of other poems, usually intended to be sung in taverns.

Which leads to the conclusion that, for all of its notorious musical difficulty, the secret to singing the national anthem might be, if not getting somewhat bombed to sing it, simply relaxing a bit and not trying so hard.

Once paired together, “The Anacreontic Song” and “The Star-Spangled Banner”—originally named “Defense of Fort McHenry”—took a very long while to be officially instated as America’s national anthem. Believe it or not, it wasn’t until 1931, following a derisive newspaper cartoon by Santa Rosa’s Robert Ripley in his syndicated “Believe It or Not” series, that Congress finally passed a bill that named “The Star-Spangled Banner” the country’s national anthem.

By then, it had already become common for the song to be performed at the beginning of baseball games, a tradition that supposedly began at the 1918 World Series in Chicago, when it was played by a military band during the seventh inning. The tradition took a while to spread to every single game, in part because of the cost of hiring a full military band.

Today, the singing of the national anthem is as much a part of the baseball experience as are the consumption of hot dogs and a willing overpayment for beer. The Giants, as do all other baseball franchises, annually receive thousands of offers to perform the anthem. Through a process of online application and the sending of performance videos, those thousands are whittled down to a select group of chosen choruses, ensembles and solo singers. As of Friday, July 7, that group now includes Phillip Percy Williams.

Two days after the game (the Giants lost to the Marlins, 6 to 1), having fielded an overwhelming number of congratulations and positive reviews from friends, Williams is finally calm enough to look back at the once-in-a-lifetime experience.

“You know what was great, in a way, for me?” he asks. “It was getting stuck in traffic.

“For me, I’m the kind of performer who can get myself stressed, so it’s better to focus on something else,” Williams continues. “So I ended up stuck in traffic, and I was later to the park than I wanted to be, but that was good. I was able to walk in, do the soundcheck, pray a little and never have time to get nervous. That’s when I soar. If I sit too long waiting, the nervousness can snowball. And who needs that?”

Williams notes that, for him personally, the most powerful moment of the whole experience was during those few seconds that he spent out on the field, waiting for the cue to begin singing.

“My mom passed away a long time ago,” he says. “But she was a singer. She owned places where people sang. And she’s always been a part of my journey as a performer, even though she died when I was young, and she never got to see me do all of the things I’ve done.”

Even after acknowledging the cultural significance of singing the anthem at a Major League game, performing for such a large audience and everything else, Williams says it was that moment that he will always treasure the most.

“I took a moment to bring her in, to bring her there with me onto the field,” he says. “She was definitely there with me. I needed her to be there. And she was.”

So what’s next on Williams’ bucket list?

“I’d like to do Shakespeare, and I’d like to write a play,” he says. “One where I can sing and tell stories. I have a few really good ideas. Those are next for me, I think.”

Asked if he might one day write a show about his long journey from Mobile, Alabama, to San Francisco, from dreaming of performing to doing it on one of the largest stages in America, Williams laughs.

“Maybe,” he says. “Maybe. I mean, I did just sing the national anthem at AT&T Park. So anything is definitely possible.”

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave.

“The Anacreontic Song”

To Anacreon in Heav’n, where he sat in full Glee,

A few Sons of Harmony sent a Petition,

That He their Inspirer and Patron wou’d be;

When this Answer arriv’d from the Jolly Old Grecian.

“Voice, Fiddle, and Flute,

“no longer be mute,

“I’ll lend you my Name and inspire you to boot,

“And, besides, I’ll instruct you like me, to intwine

“The Myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s Vine.”