By Molly Oleson

Bill McKibben is worn out.

“Physically, and a little bit emotionally,” admits the founder of grassroots climate campaign 350.org to an audience that packs the Veterans’ Memorial Auditorium at the 27th annual Bioneers Conference, part of the globally celebrated movement and nonprofit organization founded by Kenny Ausubel and Nina Simons, that brings together innovators who present revolutionary solutions to the world’s most challenging environmental and social issues.

McKibben, who, later in the day, is introduced by Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace USA, as “the guy who for the last 25 years has made climate issues compelling and accessible beyond the climate science wonks,” has spent the last few weeks across the country, “trying to fight Donald Trump.”

“There’s something about the whole process, just getting mixed up in any way with that energy … ,” he says, after receiving loud applause, “so my emotions are just a little closer to the surface than I’m used to. I apologize.”

“Don’t apologize!” a woman shouts.

McKibben, a professor at Middlebury College and author of a dozen environmental books that include The End of Nature, his first, and Oil and Honey, his latest, is here to shed some light on what winning the climate change battle looks like. He joins fellow visionaries like Bren Smith—executive director of GreenWave, who works to restore ecosystems and create jobs for fishermen, and who tells us, full of hope, that “we can create something so beautiful and restorative out at sea,” and 16-year-old Indigenous activist and award-winning Youth Director of Earth Guardians, Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, who tells us that every living thing is sacred, and that we must “give back to the Earth everything that we take.”

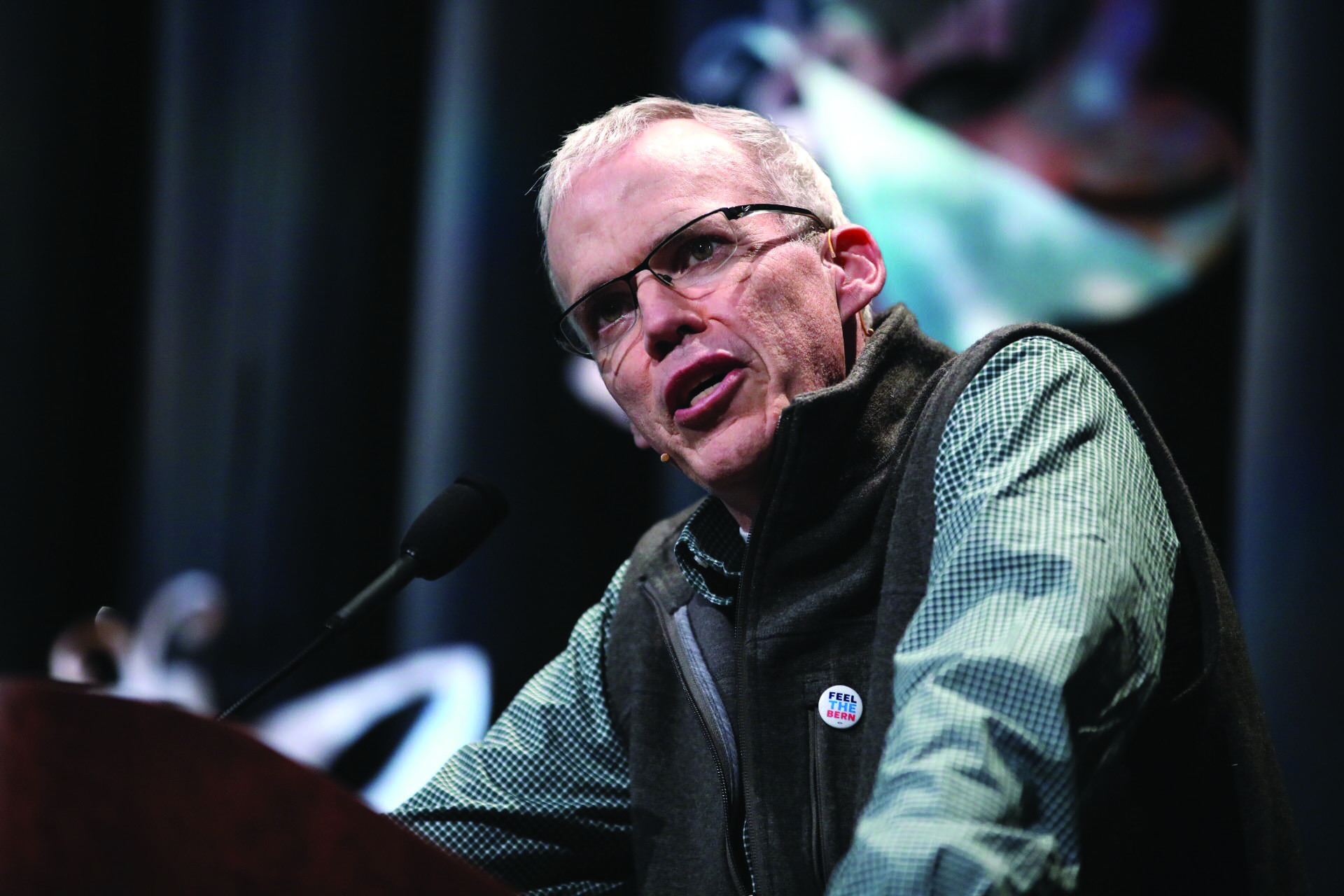

McKibben, wearing a gray vest and a tiny “Feel the Bern” button, takes a moment before laying out the environmental landscape—past, present and future. Leonard will tell us later that the influential climate activist “distills impending global catastrophe into simple statements and mathematical equations that everyone can understand, and then, more importantly, be inspired to take action.” We wait patiently, ready to take whatever he says to heart.

“The vision rising in my mind, of our planet, is—at least the first of them—is lights turning off,” McKibben says. “Our big, beautiful, buzzing, glorious, mysterious, cool, interesting planet looked at from a distance … some of the lights are starting now to blink out—and, in the saddest possible ways.”

The Arctic, he says, as of yesterday, has the lowest extent of sea ice that we’ve ever measured on that date. “So that’s literally a light going out, a big white mirror that used to reflect 80 percent of the sun’s incoming rays.”

He speaks of the great wave of hot water sweeping across the Pacific and the Indian oceans this past spring, wiping out 80 to 90 percent of the coral—”structures so big you can see them from outer space,” there since as long as anyone can remember.

He talks of the devastation in Haiti when Hurricane Matthew ripped through 10 days ago. A city on the southwest peninsula that was wiped out stuck in his mind, and he went back and looked at pictures from one of 350.org’s demonstrations. “And that one stuck in my mind, the picture from that town in Haiti,” he says. “And it was an amazing picture … some young people has assembled a big banner and all they said on it was—this was their message to the world—“‘Your actions affect us.’”

And of course they’re right, he continues. When the lights go out, McKibben warns, “No one will see us, know us, need us. And it’s not just individuals—we’re now watching species blink. Out. On. This. Planet. Chains of creation that stretch back a very great ways. And it’s not as if these lights are just turning off on their own. They’re being turned off.”

McKibben becomes agitated when he speaks of Exxon, the largest fossil fuel company on earth, knowing years and years ago everything there was to know about climate change. “That their scientists had a complete understanding of how fast the planet was gonna warm, and they used that to make sure that they would, say, build their own drilling rigs high enough to compensate for the rise in sea level they knew was coming—that they knew all that and instead they spent tens of millions of dollars helping to persuade everyone that it wasn’t happening. And that we shouldn’t take it seriously, and helped us waste a quarter century—maybe the crucial quarter century—in a completely pointless argument about whether climate change was real or not. Well, that’s what’s turning lights off. And I don’t even really even have words for that.”

But there’s another vision, McKibben says. One of lights starting to blink on, all over the planet. “Some of those lights, like bulbs, going on in the minds of our great engineers. In the last 10 years, the price of a solar panel on this planet’s come down 80 percent as the engineers have done their job … that’s the most important economic path on the planet, it opens up a world of possibilities, should we choose to use them.

“And lights going on in the minds of visionaries,” he continues. “Down the road from here at Stanford, Mark Jacobson and his team have figured out what it would take in every state in the union, in every country on earth to make this world run on renewable energy by 2030 at a price that we could afford.”

The audience cheers loudly. “That’s a bright light … ”

McKibben mentions East Africa as another light coming on. “Especially right now, where the fossil fuel revolution of the last 200 years meant basically nothing except perhaps a kerosene lamp in your home. Now every day, thousands and thousands and thousands of people’s huts and homes are turning solar and turning solar fast, and it’s beautiful to watch the lights come on and people able to study and read. And we can do it … everywhere. Everywhere. So many of those seeds of that new light were planted in this room and at these conferences over the decades—so many of the ideas that we need to move forward, and one can look around and be hopeful about those lights going on. But—They. Are. Not. Going. On. Fast. Enough. Not anywhere near fast enough. We’re not staying ahead of the darkness at this point.”

The year 2016 will be the hottest year we’ve ever measured on the planet, he says, beating the records that we set in both 2014 and 2015. “July and August were not only the hottest months we’ve ever measured on this planet, the scientists who studied the records that go back before thermometers are pretty convinced that July and August were the two hottest months in the history of human civilization.” He lets out a big sigh.

“So with these two visions of lights going off and lights going on, it seems to me that our job becomes to light as best we can the flames of resistance,” he says. “That resistance, that movement, is the only thing that can make the difference. The stories we tell each other can’t be about the solar panels on our particular roofs or our particular net zero homes or our particular lives … [applause] those are very good things. But they’re not the thing. Those stories of ‘I’ have gotta be replaced by stories of ‘we.’”

There is enough carbon in the coal and gas and oil fields already in production to take us past the 2-degree increase in temperature that was set as the absolute red line, McKibben says. “That means that we cannot allow anything new to get built. Nothing. No more frack wells, no new coal mines, no more pipelines. Nothing! It is possible to do this.”

Changing the ending, or at least trying to, is all McKibben wants to talk about as he closes. “I’ve been telling you a story because I’m a writer. A story about—well, really the oldest possible story about light coming on, and light going off. And that’s where the good book begins and so many other of our scriptures and accounts. I. Don’t. Know. How. This. Story. Ends. The ending’s not written yet. It’s possible that the ending is gonna be terrible no matter what we do because we have waited a very long time to get started and the momentum of physics is enormously strong, and when you begin to lose the largest physical features on your earth like the ice caps in the Arctic, that is a bad sign. But I am utterly confident that the ending will be less terrible if we fight.

“And I think that some of it will be beautiful,” he continues. “In fact that it won’t be an ending at all. That we have it still within our power to make change enough on this planet that we pass it along, not in as good order as we found it … but pass it on at least in a condition that will make it possible for the next generations to go on fighting for it, too. And at this point, that’s, I think, what we have to aim for.

He tells us not to worry too much about the ending, about how it comes out. “Just give it what you’ve got—all that you’ve got.”