A Story in Two Parts. Read the second part here.

On the muddy banks of the Petaluma River in downtown Petaluma, a new housing complex is rising. Crews employed by the A.G. Spanos Corporation, a Stockton-based developer, are constructing a 184-unit apartment complex on a lot sandwiched between a row of historic businesses and the tidal slough.

Before laying out the concrete foundations, the crews ripped out a few hundred feet of railroad tracks that crossed the lot. The old rails were part of a spur located less than a mile off the century-old main line running between Sausalito and Eureka. Planning and construction could not commence until Spanos controlled the legal “rights of way” on the tracks.

Rights of way are contractual easements that allow their owners to travel across another’s property. In this case, the easements on the riverfront tracks had value because the developer needed to extinguish them in order to build. That fact cost Spanos millions of dollars.

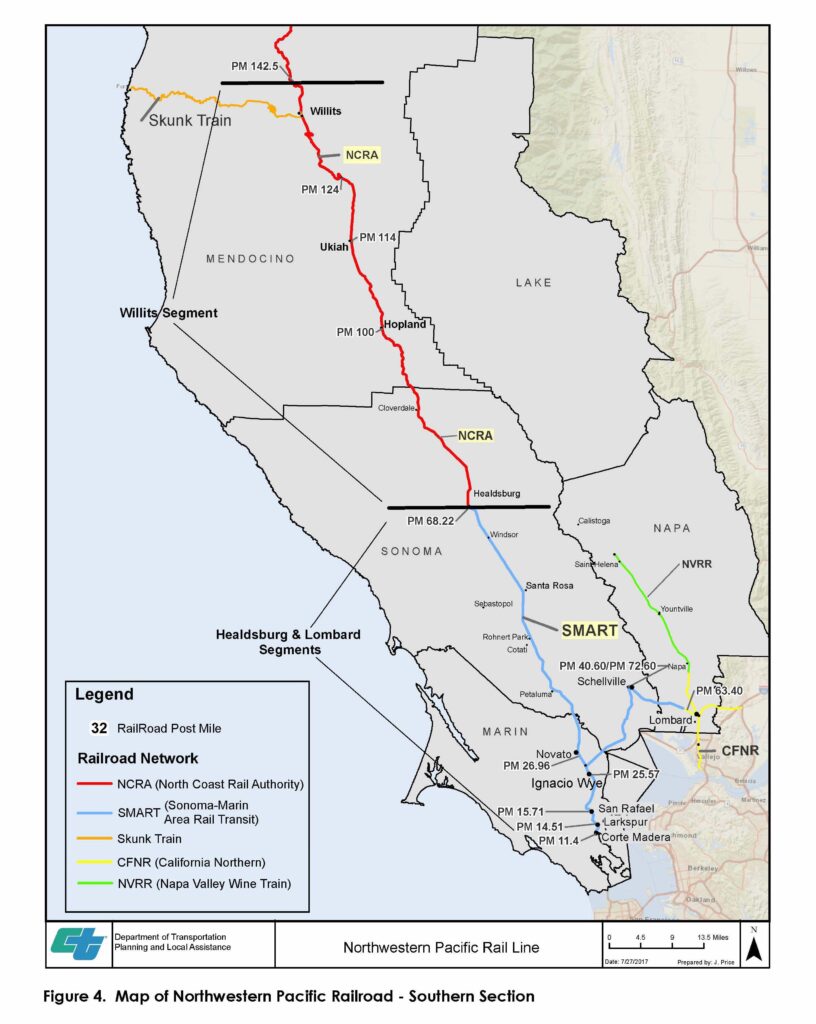

Public records reveal that lengthy negotiations between the Spanos corporation and two state-created rail transportation agencies for ownership of the rights of way preceded breaking ground for the construction project. One right of way was owned by a passenger line, Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit district — SMART. A second right of way was owned by a state-owned freight line, North Coast Railroad Authority (NCRA). Both railway agencies saw the sale of the easements as potential cash cows.

In April 2017, Spanos reached an agreement with the two agencies, shelling out $2.4 million for the right to remove the track. But that is not the end of the story. Millions of taxpayer dollars have been deployed to bail out and close down the NCRA, which leases the right to use its rails to a private company called Northwestern Pacific Railroad Company, or NWP Co.

Public records reveal that two Sonoma County businessmen — Darius Anderson and Doug Bosco — played central roles in the backdoor negotiations for the easement sales.

Who are they and why does this story matter?

Darius Anderson is a real estate developer who owns Platinum Advisors, a powerful California lobbying and political consulting firm. He also owns the Press Democrat.

Records show that during the negotiations over the railway easement sales price, Anderson apparently leveraged Platinum Advisor’s position as a SMART lobbyist to, in effect, benefit the aforementioned Northwestern Pacific Railroad Company or NWP Co, which is controlled by another Press Democrat owner, former congressman Doug Bosco.

Records obtained by the North Bay Bohemian and Pacific Sun using the California Public Records Act reveal that SMART director Farhad Mansourian allowed Anderson to guide SMART’s participation in the Petaluma right of way deal, even though that task was outside of the scope of Platinum Advisor’s state lobbying contract with SMART. Mansourian also asked Anderson to lobby federal lawmakers, another task outside the scope of Platinum’s original contract.

During his five years representing SMART, Anderson’s firm lobbied for state and federal legislation involving the fate of Bosco’s private freight company. SMART paid Platinum Advisors $600,000 before the contract ended in February 2020.

In order to grasp why the lobbying contract and the railway right of way deals stink of conflicts of interest, we must take a step back into the recent history of rail freighting in the North Bay, a domain which Bosco and his allies have overseen for at least 15 years, with financial consequences that are not in the public’s best interests.

How It All Began

Our story starts with the gradual demise of a once-lucrative railroad line stretching about 300 miles from Sausalito to Humboldt Bay that chugged into existence in 1914.

At first, sections of the Northwestern Pacific Railroad were operated by a potpourri of privately owned companies that profitably hauled lumber and other commodities up and down the North Coast, while also operating passenger trains.

However, the rail line’s profitability was ultimately doomed by the decline of the North Coast’s resource extraction industries, a catastrophic tunnel fire in 1978, and an endless series of floods. In the 1980s, storm-induced landslides destroyed the mid-section of the line, running through the Eel River Canyon. Increasingly, the railway appeared to have no future.

Trying to preserve the viability of the defunct rail line for freighting, state lawmakers created the North Coast Railroad Authority in 1989. Over the next two decades, state and federal agencies spent $124 million purchasing the railroad from various private companies and funding the NCRA’s efforts to restore sections of the decaying track for use by freight trains. But the hoped-for regeneration of the historic railroad was stymied by the failure of the California government to consistently fund the substantial costs of restoring the entire rail line and the NCRA’s ongoing operating costs.

Enter Bosco

In June 2006, a group of businessmen formed the privately owned Northwestern Pacific Railroad Company or NWP Co. The venture was designed to rejuvenate the freight line by creating a “public-private partnership” with the flailing NCRA to reopen the entire line. In short, NCRA and NWP Co would collaborate to improve and maintain the rail infrastructure using public and private funds. NWP Co would privately lease the right to operate freight trains from the NCRA and (somehow) make money.

Among NWP Co’s founders was Doug Bosco, a former state assemblyman and congressman who had worked on transportation issues at the state and federal levels during his time in office.

According to the NWP Co business plan submitted to the California Transportation Commission in October 2006, Bosco and his partners had grand plans. The document outlined multiple business prospects which NWP Co claimed would allow the company to generate annual revenues of more than $3 million within a few short years.

First, on the southern end of the line, NWP Co projected annual revenues of about $1.1 million hauling lumber and agricultural products. The company estimated revenues of about $2 million transporting garbage from Sonoma County’s landfill to a solid waste dump in Nevada, with which it claimed to have an “exclusive right to negotiate” for 200 years.

If reopened, the northern end of the line would be even more lucrative, NWP Co claimed. The company asserted that it would partner with Evergreen Natural Resources to transport rail cars packed with gravel from the Island Mountain Quarry at the border of Mendocino and Trinity counties. Once the decaying rail lines to the quarry were reopened, the gravel shipping business could generate revenues of “at least $30 million per year,” the business plan stated.

As the general counsel for NWP Co, Bosco would “assist in the interface between NWP Co. and NCRA and various funding agencies in order to ensure … that the public agencies’ reimbursement funding flows smoothly to NCRA,” according to the NWP Co business plan. Public records show that Bosco now also serves as CEO of NWP Co.

If the company’s Island Mountain plans had panned out, NWP Co — and the NCRA in turn — would have gained a rich stream of income. At the time, the NCRA estimated the capital cost of rehabilitating 300 miles of rails was $150.6 million — $42.6 million for the portion south of the Russian River, and $108 million for the northern Eel River Division, according to NWP Co’s plan. A Los Angeles Times report in 2001 was less optimistic, citing a federal study which calculated the cost of reopening the entire line for freight and passenger rail at $642 million.

The NCRA-NWP Co main lease agreement was signed in September 2006. In 2011, the NCRA and NWP Co started running freight cars along 62 miles of refurbished track in the North Bay. But, according to a recent report by SMART, the freight revenue appears to be lower than the amounts originally projected by NWP Co. Nor did Bosco’s company secure a contract to ship Sonoma County’s waste to Nevada. And the Island Mountain quarry project, and other shipping opportunities potentially served by rejuvenation of the northern two-thirds of the line, never materialized.

To make up for the shortfall between revenues and capital, legal and operating costs, the NCRA entered into a complex series of loans and contracts with NWP Co, which somehow resulted in the publicly chartered rail agency owing millions of dollars to the privately owned NWP Co.

“An impartial outside observer … could conclude that … the public is not currently getting — and may not ever get — the benefit of tens of millions of tax-payer dollars used in the line’s rehabilitation.”

Bernard Meyers

But a 2020 state assessment of the NCRA — in effect, an autopsy — examines how the public rail agency’s intertwined relationship with the private NWP Co came to pass. Remember, the NCRA was theoretically created for the purpose of saving the publicly owned railroad, but it became, in effect, forever indebted to Bosco’s privately owned company, according to government reports and a former NCRA board member.

According to the report, prepared by a handful of state agencies, including the California State Transportation Authority and California Department of Finance, “When the Legislature created NCRA, it did not designate NCRA as a state or local agency and did not appropriate funding for its operations. Since its inception, NCRA has covered its expenses from rail revenues; state grant funding; public and private loans; loan forgiveness; proceeds from lease agreements; and leasing or sale of assets.” (Since it never received much revenue from its lease agreement with NWP Co, NCRA’s most valuable assets became the excess properties and rights of way it owned up and down the line, including the property rights on the Spanos lot bordering the Petaluma river — and we shall return to that story.)

For decades, California agencies have been wary of funding the NCRA due to its convoluted accounting practices, which are intertwined with the accounts of NWP Co. CalTrans and FEMA have long branded the NCRA a “high risk” recipient of state and federal funds.

A Sweet Deal

Bernard Meyers, a former NCRA board member, says that the NCRA’s long-running debts to NWP Co and its myriad financial problems can be directly traced to the problematic 2006 lease agreement with NWP Co.

Mitch Stogner has served as executive director of NCRA since 2003. Stogner worked as Bosco’s chief of staff for 15 years, first in the California Assembly (1976-1982), and then in Congress (1983-1991).

Remarkably, the 2006 agreement states that NWP Co is not required to pay rent on the tracks until the company has booked $5 million in net revenue in a single year — “net” meaning $5 million after taxes and other expenses. Because NWP Co has not met the $5 million threshold, it has paid very little to the NCRA for the use of the tracks.

Between 2006 and 2019, the NCRA “entered into 8 agreements, 7 amendments, and 1 informal financing arrangement with NWP Co. to fund NCRA’s operations,” according to the 2020 state assessment. The partially revealed paper trail delineates a strange relationship between the two, with NCRA acting as landlord and NWP Co acting as tenant. It’s a relationship in which the tenant does not pay rent, because it does not net more than $5 million a year, but it has enough, somehow, to loan the landlord millions of dollars to cover rail maintenance and capital construction costs.

Without the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars, however, reaching the $5 million annual revenue benchmark was clearly a pipe dream.

Meyers represented Marin County on the board of the NCRA for six years. In 2013, he wrote a brutally accusatory and detailed exit memo to his colleagues laying out a litany of complaints about the way the NCRA was run — and whom the oddly crafted agency seemed designed to benefit.

“An impartial outside observer coming afresh to the NCRA’s books and the NWP lease could conclude that this organization is primarily run for the benefit of its lessee, NWP Co., that the public is not currently getting — and may not ever get — the benefit of tens of millions of tax-payer dollars used in the line’s rehabilitation, and that public benefit was not a primarily intended consequence,” Meyers wrote.

Four years later, in June 2017, the California Transportation Commission revisited the financial status of the NCRA after state staff noticed that a recent audit had raised “substantial doubt about NCRA’s ability to continue as a going concern.” Testifying to the Commission, Stogner did not deny the charge of insolvency. Instead, he leaned into it, commenting that such a concern “is a comment that our auditors have made for at least the last seven or eight years” due in part to the fact that the agency did not have a dedicated source of state funding. As a remedy, Stogner proposed that the state transfuse the moribund NCRA with cash plasma. Instead, in January 2018, the commission signaled its support for the state legislature to shut the NCRA down, a process which has been dragging on and on.

In early 2018, State Senator Mike McGuire introduced legislation to transform much of the 300 mile long railroad right of way into a bike and pedestrian trail dubbed the Great Redwood Trail, running from Larkspur to Humboldt Bay.

This legislation requires the freight business on the southern end of the line, where its lessee, NWP Co, had been running freight since 2011, to be controlled by Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit district, SMART. The passenger rail agency was created by state legislation in 2002. It is funded by a combination of federal, state, and local tax dollars. When NWP Co started to run freight on the NCRA rail lines in 2011, it agreed to share the rails with SMART. In August 2017, SMART started to run passenger trains.

Enter Anderson

On Jan. 1, 2015, SMART hired Darius Anderson’s Platinum Advisors to represent the transit agency’s interests in Sacramento.

By choosing to hire Platinum Advisors, SMART’s board of directors chose a firm with deeply intertwined business and political interests in the North Bay.

Anderson is a North Bay native who reportedly got his start in politics as a driver for Bosco in Washington D.C.

He went on to work for billionaire Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Investments. Burkle has partnered with Anderson in real estate ventures, such as developing Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. In 1998, Anderson founded a Sacramento-based lobbying firm, Platinum Advisors. Public records from 2018 show that Burkle is Anderson’s “partner” and that Burkle “owns ten percent or more” of the political consulting firm.

Notably, in 2017, San Francisco Superior Court found that Anderson and Doug Boxer, the son of former US. Senator Barbara Boxer, had defrauded the Federated Indians of the Graton Rancheria while working as consultants to the tribe’s casino venture in the early 2000s. Anderson was ordered to pay $725,000 to the tribe to cover its legal fees and arbitration costs in the civil action. Defrauding the Graton Rancheria does not seem to have negatively affected Anderson’s reputation amongst the political and corporate classes, however. Today, Platinum Advisors represents dozens of public and private clients from its offices in San Francisco, Sacramento and Washington D.C. Anderson enjoys insider access to many Democratic and Republican politicians, as he is a prolific campaign fundraiser.

In 2011, Anderson and Bosco joined forces as founding members of Sonoma Media Investments, which now owns most of the print media in Sonoma County, including the Press Democrat, Sonoma Index-Tribune, Sonoma County Gazette, Petaluma Argus-Courier, North Bay Business Journal, Sonoma Magazine, and La Prensa.

SMART’s contract with Platinum Advisors includes a conflict of interest clause, requiring Anderson to promise that he and his firm did not own — and would not develop — any “direct or indirect” financial holdings which conflict with their work for SMART.

The contract allowed SMART to ask Anderson and his employees to divulge their economic interests, but SMART spokesperson Matt Stevens said that SMART’s outgoing director Farhad Mansourian, who directly oversaw Anderson’s work, did not request such disclosures, and that SMART staff was “not aware of any financial conflicts of interests that would conflict in any way with Platinum Advisors performance regarding its services.”

Darius Anderson did not respond to requests for comment.

Mansourian deployed Platinum Advisors to push for state funding and favorable legislation in Sacramento. And he often turned to Anderson and Platinum Advisors’ transportation specialist Steven Wallauch to lobby state officials on legislation involving the NCRA and Bosco’s NWP Co, according to emails obtained by the Bohemian/Pacific Sun through a public records request. On multiple occasions, Mansourian also requested that Bosco himself contact the governor’s office and federal lawmakers on behalf of SMART.

When McGuire introduced Senate Bill 1029 in 2018, it needed language to effectuate the closure of the NCRA’s debts and business relationships with its contractors, chief among them Bosco’s NWP Co.

Emails show that Bosco was involved in crafting the legislation.

On June 27, 2018, Mansourian emailed Anderson for an update on the legislation: “Did you talk to Doug?! … Should we go and see Governor’s chief of staff on SB 1029 ??”

Anderson responded the next day: “I did talk to Doug. Once they have language solidified, they will go to the Governor’s office.”

“What language? Who is working on that?” Mansourian asked.

“There is language being worked on to pay off the debts and liabilities. I am sure that Jason [Liles] will be sharing with us all before it moves forward. It’s the same language that you are working on with Jason,” Anderson wrote. Jason Liles, the McGuire aide working on the legislation to close down the NCRA, is also a Bosco alumnus.

The last paragraph of McGuire’s bill, as signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in September 2018, allocated $4 million in state funding to SMART “for the acquisition of freight rights and equipment from the Northwestern Pacific Railroad Company [NWP Co].” At a board meeting last May, SMART’s directors agreed to purchase NWP Co’s freight rights and equipment for $4 million, and to add freight services to its passenger rail offerings.

Liles did not respond to requests for comment. SMART’s spokesman said the agency’s staff does not know how the $4 million figure was reached. Bosco wrote “I do not recall where the $4m sales price came from,” but called the price a “bargain” for the state. The 2020 state assessment of the NCRA, which was prepared and published after the $4 million figure was calculated, argues that SMART taking ownership of freight service in the North Bay will have some financial benefits over allowing a separate private freight company to purchase the freight rights from NWP Co.

In subsequent NCRA-related bills authored by McGuire, the state set aside more millions of dollars to cover NCRA debts. On top of paying $4 million to NWP Co for freight rights and equipment, the state paid NWP Co $3.47 million to cover NCRA’s interest-bearing debts to the company, according to Garin Casaleggio, a CalSTA representative.

That amounts to a $7.47 million cash payout to the NWP Co enterprise that had failed to deliver on the prospects it outlined in the 2006 business plan. It does not look like the freight rail business is going to do any better under SMART, however.

The move to take on the additional responsibility of running a freight line came at a trying time for SMART. On March 3, voters in Sonoma and Marin counties rejected Measure I, a ballot item intended to extend the sales tax supporting SMART from 2029 to 2059 — giving SMART a financial buffer for decades to come. Weeks after the failure at the ballot box, a global pandemic hit, crushing the agency’s ridership numbers and casting further doubt on the passenger train’s long-term viability.

Bosco, who appeared at a virtual SMART meeting in May 2020, wasn’t much help in predicting the future. Asked about his company’s current revenue, Bosco wouldn’t give a specific answer.

“I don’t want to disclose the exact numbers because that’s our proprietary information. But I can tell you that we take in about $2 million in revenues a year,” Bosco said.

Yet, despite having few details about how much money Bosco’s freight company earned or spent, and lacking an assessment of how much it would cost SMART to take over the freight operation, 11 of SMART’s 12 board members voted in favor of the paying off and taking over NWP Co’s freight operations at the May 2020 meeting.

The supporters of the decision highlighted the fact that Senator McGuire and state officials had endorsed the deal, and that McGuire promised to secure $10 million in state funding over the coming years to cover SMART’s freight startup costs. Still, it remains unclear to this day how much it will cost SMART to cover day-to-day freight operations or how much revenue the business is expected to bring in.

Adding to the pressure, SMART staff told board members at the May 2020 meeting that the board had to make a decision by June 30 or risk losing the state money on the table.

Only one board member, then-San Rafael Mayor Gary Phillips, abstained from supporting the takeover, citing a lack of financial information.

“We’ve been told by Mr. Bosco, and I like Doug, that it’s highly profitable or at least profitable. I don’t have anything — I don’t know if any of us have anything that would indicate that. And so we’re going to take on this obligation with the unknowns that are present. I think that, quite frankly, would be quite foolish of the board,” Phillips said during the meeting.

This February, SMART contracted with a Marin County consultant, Project Finance Advisory Limited, to study the feasibility of the freight takeover plan the agency’s board had approved nine months earlier. In early September, the consultant provided board members with an executive summary of the report. The full report is not complete, according to Stevens, the SMART spokesman.

The executive summary is revealing about NWP Co’s business history, even though Bosco’s company declined to disclose its operating costs to the consultant.

The document estimates that NWP Co’s freight business brings in between $1.2 and $1.3 million per year by hauling agricultural products to four North Bay manufacturers, including Lagunitas Brewing Co. and Hunt & Behrens, Inc., and storing excess railroad equipment and liquid petroleum gas for Bay Area refineries. Although most people associate freight companies with transporting goods, the report estimates that nearly half of NWP Co’s revenue comes from storing rail equipment and “LPG” filled tankers at a train yard near Schellville.

The report cannot estimate how much it costs NWP Co — and by extension will cost SMART — to offer freight services because “detailed, itemized financial records for NWPCo. were not provided” to SMART.

The report posits that running freight cars can offer a “comfortable profit margin,” but it’s not clear how many, if any, North Bay companies are interested in switching from conventional trucking to rail freight.

Since the actual freight operating costs are unknown, outsourcing operation of the freighting back to NWP Co or another contractor could run up a deficit for SMART, which is having enough trouble trying to provide adequate passenger services.

While SMART studies the North Bay’s freight market, NWP Co has continued to serve its customers without paying SMART.

In his written response to the Bohemian/Pacific Sun’s questions, Bosco said that “The NWP/NCRA lease has not yet been transferred to SMART nor has NWP relinquished its operating rights. Accordingly, NWP is not paying rent to SMART.” Stevens, the SMART spokesman, confirmed that NWP Co continues to run freight under its lease agreement with the NCRA while SMART and NWP Co negotiate an interim agreement.

Next week, the Bohemian/Pacific Sun will report on the secret negotiations over the price of the rights of way in Petaluma that took place between Bosco, Anderson, the Spanos Corporation, and SMART.