Could Sir Francis Drake have discovered San Francisco Bay, 190 years before history books say Gaspar de Portolá did? Amateur historian Duane Van Dieman has evidence—“a discovery,” he calls it—that he says may upend the accepted wisdom about Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe more than 400 years ago.

The location of Drake’s fateful landfall in 1579 has been debated for 200 years. The commonly accepted site is Drakes Estero in the Point Reyes National Seashore. The location was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 2012 as the “most likely” site of Drake’s California landing. But Van Dieman never bought the Drakes Estero location and spent 10 years researching other sites.

“Someone has got to find this,” he said as he began his quest in 2001. “Why not me?”

He said he stumbled on the location a decade ago after he had given up his search, but he kept it a secret as he tried to prove and disprove his theory. But now he’s ready to go public. Van Dieman believes Drake landed in a tidy cove just east of Highway 101 in Mill Valley, making him the first European to enter San Francisco Bay.

The jury is still out but, this much we know for sure. In 1579, Capt. Francis Drake, sometimes referred to as “the Queen’s pirate,” led his crew of the Golden Hind northwest from South America in search of a way back home to England. The ship was laden with 40 tons of silver and assorted stolen booty, including 26 tons of silver from a Spanish galleon nicknamed Cacafuego (a derogatory term that meant “braggart” or, literally, “fireshitter”) off the coast of Peru. Drake was apparently a polite pirate. After looting the ship, he invited the officers and first-class passengers on the Spanish ship to dinner and sent them off with parting gifts befitting their rank and notice of safe passage.

Drake was eager to present his treasure to Queen Elizabeth I and receive the fame and fortune that surely awaited him. Having rounded the tip of South America through the Straights of Magellan on his way up the coast of the Americas, Drake was hoping to find the fabled Northwest Passage through Canada and back into the Atlantic Ocean. That was not to be.

Drake reportedly got as far north as British Colombia before deciding to turn around in icy weather, with a leaking hull to boot. He needed to find a safe harbor to make repairs for his return voyage. He would go on to be the first ship’s captain to circumnavigate the globe and return home. (Ferdinand Magellan was the first to circle the earth, but he never made it home).

But first Drake had to fix his ship.

The coast of what is now Canada, Washington, Oregon and Northern California proved too rocky and dangerous to drop anchor. But according to an account compiled by Drake’s nephew in 1628, as the captain and company sailed south, they “fell with a convenient and fit harbor and June 17 came to anchor there.”

But where exactly Drake landed and spent the next five weeks is one of the world’s great riddles. Original maps and logs from Drake’s voyage burned in the Palace of Whitehall in 1698. A map of the Marin County coast reveals the accepted wisdom in the place names Drakes Bay, Drakes Estero and Drakes Cove. The Drake Navigators Guild, a private research organization founded in 1949, spent years studying the Drakes Estero site and was instrumental in securing federal recognition of the site as a national landmark.

In a 2012 story in the Press Democrat following the dedication of the site by the U.S. Department of the Interior, the late Edward Von der Porten, maritime archeologist, historian and president of the Drake Navigators Guild at the time, said the official recognition ended the debate. “Were there any scholarly debate, this would not have happened,” he was quoted as saying.

Mike Von der Porten, vice president of the guild and Edward Von der Porten’s son, says there are some 50 data points that indicate the mouth of Drakes Estero was where the privateer found safe harbor and peacefully interacted with the native Miwok Indians, making the expedition the first time English was spoken in what would become the United States.

“It all comes together,” says Mike Von der Porten.

He argues Drake could not have found San Francisco Bay because it was too foggy to see, and if he had, he would have explored it and told the world about it. He scoffed at Van Dieman’s theory.

Case closed? Not by a long shot.

In addition to the National Park Service’s hedge that Drakes Estero is “the most likely site” of the landing, the Press Democrat article quotes a National Parks spokesperson who says the designation “should not be interpreted as providing a definitive resolution of the discussion.” (Mike Von der Porten says the spokesperson “wasn’t the most knowledgeable” and his quotes “continue to haunt us.”)

The Wikipedia entry for Nova Albion, the term that Drake gave to the region that means “New Britain,” lists 20 different “fringe theories” that locate Drake’s fateful landfall at different spots in San Francisco Bay, Bodega Bay and as far north as British Columbia. Some seem easily dismissed. Given that there were no Miwok Indians in Canada, it’s safe to rule out British Columbia.

One of the entries cites Van Dieman. Van Dieman grew up in Mill Valley and is a longtime student of local history. He worked as a docent in the Mill Valley History Room for five years and became fascinated with the Mt. Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railway. He is also a member of the Tazmanian Devils, a locally celebrated rock band from the 1970s and ’80s. The band still plays the occasional gig.

With his peaked, black leather duster hat, purple bandana and trim beard, Van Dieman, 66, looks like a slimmer Waylon Jennings. For the past 10 years, what has really captured his interest is Sir Francis Drake and the mystery of Drake’s landing site.

“It’s always been an enigma,” he says. “It’s like trying to hug a ghost. There is no there there.”

After years of false starts, giving up and starting over again, Van Dieman says he discovered a spot he says fits perfectly with all the clues left by Drake: Strawberry Cove, an inlet of Richardson Bay near Seminary Drive, now ringed with condominiums.

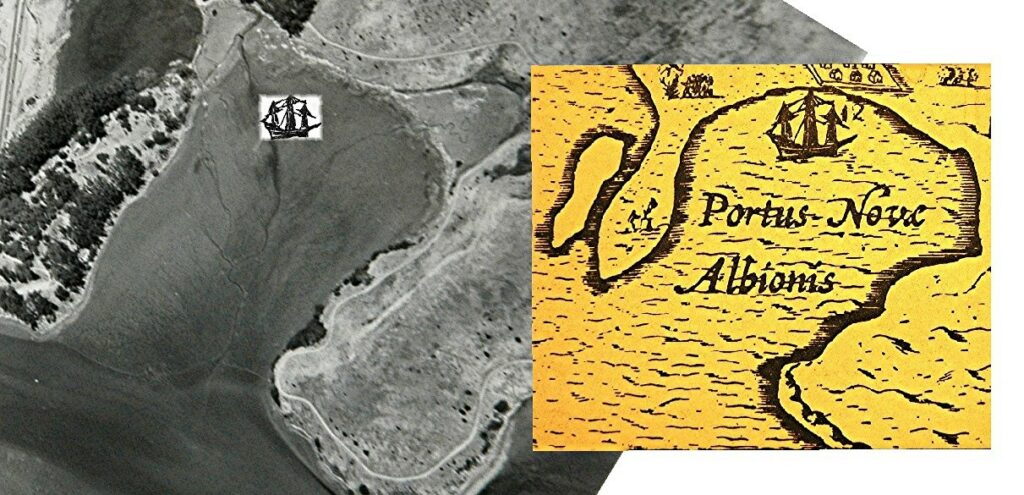

One of most tantalizing bits of evidence about Drake’s trip to California is the “Portus Plan of Nova Albion,” a drawing of the spot where Drake landed and repaired his ship. The image depicts a small cove surrounded by hills with a peninsula on one side flanked by what appears to be a flat island. Adherents of the Drakes Estero theory say the flat island is a sand spit that comes and goes with the tides. Using old nautical charts, historic photographs and other research materials, Van Dieman says the telltale landmark is actually a marsh island, now mostly covered by landfill. But there is a culvert that runs where the channel between the island and the peninsula would be, says Van Dieman. Lay the Portus Plan over a map of Strawberry Cove, and they two line up quite well.

“You don’t have to be a Drake expert to say that it looks like match,” says Van Dieman.

Van Dieman runs through a list of other clues contained in Drake’s nephew’s account of their time in California that all check out. The details of his findings are on his website, sfdrakefoundation.org.

Van Dieman came upon the cove by chance in 2008. He had long since given up on his quest to find the site and was out on a drive after recording a voice actor who happened to be reciting a famous speech by Queen Elizabeth I. “It was a magical day,” he says. He found himself on Richardson Bay, suddenly on the alert for landmarks and water features that might match the written and illustrated descriptions of Drake’s landing. He rounded a corner and beheld Strawberry Cove. Everything added up: the shape of the cove, the hills, the flora and fauna, the weather, the peninsula.

“I knew if I found it,” he says, “it would have to be perfect. And it was. I went into shock. I might have solved a 200-year-old mystery.”

After securing permits to search the area (archeological exploration is illegal without proper approval), Van Dieman admits he found no archeological evidence other than some decomposed iron. There may be artifacts under Seminary Road, he says. But he’s convinced he’s right and Drakes Estero is wrong.

“After years of dedicated historical and scientific research by myself and a team of experienced historians, archaeologists, geophysicists and geologists,” he writes on his website, “I can now say with confidence that the true location of this great chapter in British and American history is almost certainly a well-known southern Marin cove that many thousands of people look at every day.”

John Sugden, British author of Sir Francis Drake, the definitive biography of Drake, has taken an interest in Dieman’s investigation of the Strawberry Cove site. “Your theory ought to be up there with the others,” he wrote Dieman in an email in June.

Among other things, Van Dieman says Drakes Estero was unlikely to be Drake’s landing site because it would have been too visible to hostile Spanish ships, and the shallow, current-raked waters of the estuary would have not have accommodated the Golden Hind, a ship with a 13-foot draw.

Van Dieman says he kept his discovery secret (but somehow not off Wikipedia), and now wants to share it with the world. Before Edward Von Der Porten died earlier this year, Van Dieman presented his research to him. Van Dieman says Von der Porten listened to his presentation and called it “very interesting.”

Mike Von Der Porten, on the other hand, is irritated rather than interested in Van Dieman’s theory. “It doesn’t hold water,” he says. “If [Drake] had found the world’s best harbor, the world would have known about it.”

Van Dieman says Queen Elizabeth I forbade Drake and his crew from speaking about their trip, lest the Spanish learn of it. Van der Porten says that’s true, but the gag order was lifted after the England defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588 and England because a naval superpower, thanks in part to Drake’s stolen treasure.

But Van Dieman isn’t backing down.

“I’m sure that the Drake Navigators Guild will have something to say about my claim,” he says. “However, I’m fully prepared to debate them and to show my compelling evidence that makes a very strong case for my discovery of Drake’s landing site location to both Drake historians and to the court of public opinion.”

Excellent reporting and sleuthing!