Jared Huffman’s had it with the big telecoms when it comes to providing reliable rural broadband service to parts of his congressional district. He’s pushing a bill in congress that would give leeway to existing federal IT infrastructure in the North Bay to help solve a chronic problem with sketchy internet service in rural areas. Huffman’s bill appears to be targeted mostly at a woefully deficient Humboldt County, but it’s also applicable to Marin County.

Call it “rural broadband 2.0,” as Huffman’s push comes after a similar effort was stymied by a Republican-controlled congress that’s since given way to a Democratic majority.

His bill would give authority to agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management, the National Parks Service, the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies to “de-stovepipe” their IT systems and start working together to ramp up the internet access by creating local partnerships within and amongst themselves.

Those agencies don’t do a lot of “talking” to one another through their IT systems, says Huffman, and his bill “gives them the authority to get out of their ‘silos’ and work with others. It’s something that would drive you nuts if you knew about it,” he says—that agencies such as the Veteran’s Administration, the BLM and others all have separate contracts with the big telecoms (ATT, Verizon), but don’t have the ability to share the access with other agencies or residents. His bill provides the authority to break down these silos, he says, and encourage internet providers to look for partners including other federal agencies.

“The big picture problem,” he says, “is that rural communities are not very lucrative for the big telecoms to serve. For years, we’ve been trying to get them to serve these areas. They don’t do it, and they don’t want to do it, and they also don’t want anyone else to do it—and that’s sort of the problem too. I’m done with begging and pleading with the telecoms to take it up when they haven’t.”

Huffman’s bill would encourage partnerships similar to the one between Santa Rosa–based Sonic and the regional SMART commuter rail system in Sonoma and Marin counties. He says the Sonic-SMART partnership is a “great example for West Marin” to emulate or take a lesson from, as he encourages similar partnerships between, for example, the U.S. Parks Service, the county, a federally qualified health agency, Sonic or an ISP like it, and local community groups. It passed out of committee with bipartisan support.

A similar bill was introduced last year but died thanks to the efforts of fellow California congressman Kevin McCarthy, says Huffman. The Republican McCarthy, he says, was on the side of the telecoms last year. “They were trying to drive down the lease rates for private agencies on public lands and wanted assurances that they’d have the opportunity to lower the lease payments [the telecoms] are making right now,” he says. “I didn’t think it was reasonable to do that, and the bill is silent on that. I’m hopeful that this time around we can get it done.”

Marin County has had some success in engaging with private-public partnerships to get rural broadband to parts of West Marin. Indeed, the county has an ad hoc Marin County Broadband Task Force to deal with what’s now a decades-long dilemma with securing reliable internet access in the hinterlands.

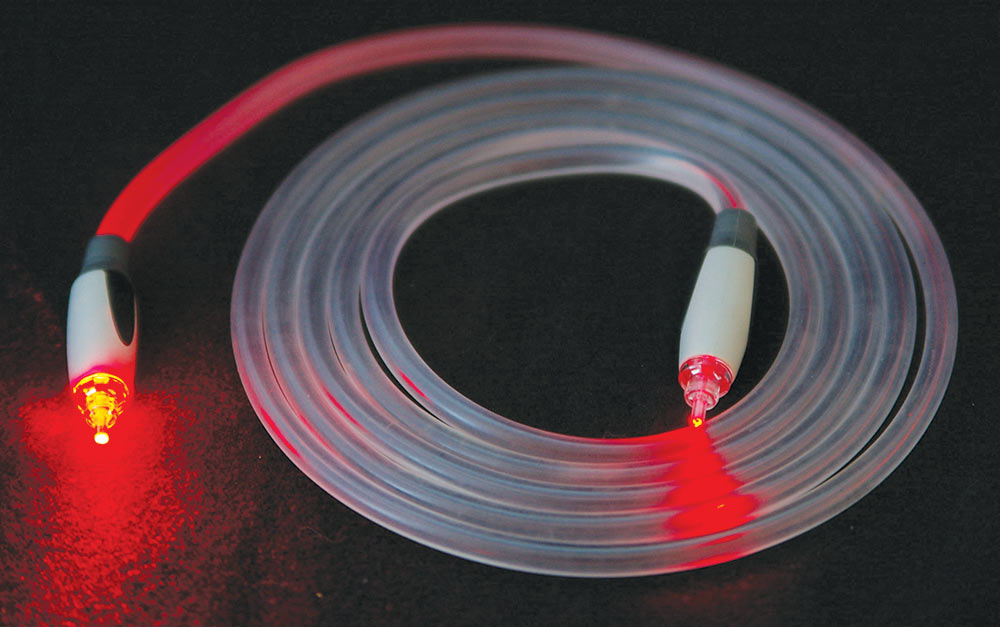

Nicasio, for example, recently installed fiber-optic cable in town and is now providing broadband service to some 80 households, businesses and other agencies, according to county documents. As of late 2018, according to county documents from the office of county IT director Liza Massey, a few are low-income residents getting the service at a discounted rate. The county reports that Inyo Networks created the Nicasio network in conjunction with the Nicasio Landowners Association; the service will eventually reach 150 customers who have ordered it.

To enhance its broadband capacity, the county hired IT consultant Peter Pratt, who noted in a city document recently that the new service helps the county achieve so-called “digital equity” through discounts given to lower-income residents. “Marin has become a broadband leader for rural California communities,” he says in a statement, “because of its determination to bring broadband to everybody, not just some.”

The Nicasio broadband push was made possible through state grants administered through the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), and the county reports that plans are afoot to “keep growing Marin’s broadband connections”—for example, in the tiny coastal town of Bolinas, which is currently serviced by AT&T and where the internet service can be rather pokey.

The broadband push is part of a larger state effort to ramp up rural high-speed internet access that took off in 2014, when some 4,000 locations in Marin “had inadequate broadband as defined by state law,” according to the county.

Marin County District 4 Supervisor Dennis Rodoni represents most of the rural parts of the county and says in a statement posted on the county website that Nicasio’s successful private-public rollout should bode well for Bolinas (and the rest of West Marin), which is currently engaged in its own “Bolinas Gigabit Network Project,” and has gotten its own $1.89 million grant from the CPUC to bring Bolinas up to speed, using Inyo Networks. Those grants have dried up.

The county estimates that once Bolinas gets its new state-of-the-art broadband fiber-optic access that it will exceed 800 fiber-to-the-home connections “in West Marin locations that previously did not have state-defined levels of broadband available.”

Once the Bolinas project is completed, those 4,000 underserved locations in Marin County will have dropped to around 700. “The state grants involved have taken time to win and move into construction,” says Rodoni in a statement posted on the county website, “but the impact to the lives of our rural communities are tremendous.”

“Any help we can get from the federal government and Congressman Huffman’s legislation is appreciated,” says Rodoni. “While Nicasio and Bolinas are on track for fiber optic/broadband through the CPUC programs, the rest of West Marin is in need of faster more reliable service and the CPUC grant funding opportunity has gone away.”

Oh, Sheep

Last month we reported on an unusual sighting (“Mall Cat,” May 1): a juvenile mountain lion had taken up residence in a planter outside of the Santa Rosa mall. This weekend we read a hair-raising account on Nextdoor about signs of a large mountain lion roaming around West Marin (possibly looking for a reliable internet connection?). Here’s a testimonial from a resident who posted about the encounter. “Last night our Anatolian Shepherd started barking furiously and pacing on our upper deck. When I went to check it out, I heard deep growling and intense guttural sounds coming from our back hill . . . Our sheep were huddled in a tight pack moving out of their sleep area like a school of fish. I found a fairly large paw print in that area this morning.” Run! Run for your life!

50’s Finished

It really did seem for a minute that after rejecting it last year, state leaders would take a serious look at Scott Weiner’s SB 50 housing bill this year—especially after he and fellow state senator Mike McGuire worked together in April to hash out a compromise bill that took some of the anti-localism sting from Weiner’s provocative housing push.

The San Francisco lawmaker’s bill would have compelled localities to build housing (some of it affordable, maybe) along transit-rich corridors—NIMBYs be darned, along with local zoning regulations. Weiner’s so-called “one-size fits all” approach to solving California’s housing crisis was met with ferocious pushback—and a compromise bill from him and McGuire that limited the proposed scope of SB 50 to larger cities (and excluding San Rafael and Novato from its reach in the process).

Well, late last week (on May 17) SB 50 died in the appropriations committee, much to the surprise of Sacramento watchers who were seemingly convinced that some version of Weiner’s bill would prevail this year, especially given the rare occurrence where the state’s construction industry and construction unions were on the same page in endorsing SB 50. —T.G.