By Josh Koehn

Eighteen life-size politicians have assembled in San Jose on the first day of the state’s Democratic Party convention in late February, and they all look stupid. Their suits and skirts and pantsuits have been flattened and covered from neck to toe in corporate and union logos. One elected official stands not far off but apart from the group, and he looks genuinely mystified by the scene of cardboard cutouts.

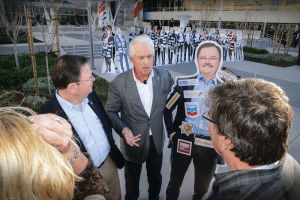

Rich Gordon, an assemblyman representing Palo Alto, Mountain View and other parts of the Peninsula, has stumbled upon a protest against the influence of money on state politics. Before he can shrug and make his way into the San Jose McEnery Convention Center, however, another man races toward him with a small group of photographers in tow.

John Cox, a 60-year-old Midwesterner who made his fortune in law and real estate, confronts Gordon with a cardboard version of the assemblyman in his hand. Cox moved to San Diego to play golf and upend the state’s political system, he says, and he wears black wingtips, dark jeans and a white dress shirt under a slate-gray blazer. His hair is white, with a sweeping part that thins at the base, and his eyebrows and nose sprout dark and white whiskers that lock like fingers.

Cox wastes no time in educating Gordon about his ballot initiative, which would force all state legislators to wear patches of their top 10 donors any time they speak or take an official action on the Senate or Assembly floor. While holding Gordon’s grinning cardboard cutout in one hand—his donor patches include Chevron, Walgreens, Time Warner Cable (none of which actually top his list) and a collection of unions—Cox tells the assemblyman that he and his colleagues should be scared of the ballot measure he’s organizing. After a brief exchange, Cox shifts tone and boldly asks Gordon if he wants to team up.

“Would you be willing to introduce this to the Assembly?” he says.

“No,” Gordon says, turning to go inside the convention.

The brief confrontation leaves Cox a bit disappointed but undeterred. “I don’t even know who he is,” he says. “I feel sorry for him. I guess he was offended. But it’s not that he’s corrupt; it’s that he works in a corrupt system.”

Shame game

No pretenses are being made that Cox’s potential ballot measure will actually improve the system. Disclosure of all campaign contributions after raising $2,000 is already required by law, and those interested in the way money moves in politics can find reports on the Secretary of State’s website. The title of Cox’s initiative, Name All Sponsors Candidate Accountability Reform, was a clever goof to use the acronym NASCAR. Just like the stickered racecars that require funding to roar around in varying degrees of left turns, or the drivers whose flame-retardant suits double as fitted billboards, it’s a nod to the fact that politicians in near-constant election cycles also have their influencers.

But considering the recent wave of corruption scandals engulfing California’s capital, the timing for such an outlandish initiative could be politically ripe. A little less than two years ago, the State Senate voted 28–1 to suspend Leland Yee, D-San Francisco, Ron Calderon, D-Montebello, and Roderick Wright, D-Inglewood. Wright resigned in September after being found guilty of felony perjury and voter fraud. Calderon, who termed out of the Senate after being indicted for allegedly accepting $88,000 in bribes, still awaits trial. In February, a federal judge sentenced Yee to five years in prison for racketeering and accepting bribes in exchange for political influence. A few days after the verdict, Cox ferried his collection of cardboard cutouts to San Francisco and San Jose to preach for political reform.

Slapping sponsors’ logos on an elected official’s suit won’t stop the money from coming in or dissuade felonious legislators from attempting to personally benefit from their public offices, but it might make legislators feel a little more self-conscious as they sing for their supper before the Senate and Assembly. Logistics, such as the size of patches or placement, are of little concern to the organizer.

“You understand: I don’t care how it works,” Cox says. “It’s just to shame them.”

Perhaps. But it could also be a way of raising the profile of a serial candidate in pursuit of elected office.

In 2000 and 2002, while still living in Illinois, Cox twice ran for Congress and lost. He had a stint as chair of the Cook County Republican Party and made another unsuccessful run for county recorder in 2004. Four

years later, Cox became the first Republican candidate to declare for the 2008 presidential nomination. He says he spoke to standing-ovation crowds in Iowa and South Carolina but called off his run because he couldn’t get traction compared to better-known candidates. He says he debated a young Barack Obama and marched in parades with currently incarcerated former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich.

“I’m a Republican and he’s a Democrat, so we didn’t have that much contact,” Cox says. “I marched a couple parades with him and knew he was an empty suit.”

Cox’s political NASCAR push, which has reportedly collected more than 70,000 signatures out of the 365,000 required by April 26 to qualify for the November ballot, is part of his larger goal to overhaul the entire State Legislature. Cox wants to break the state’s districts—40 in the Senate, 80 in the Assembly—into thousands of smaller districts: 12,000 to be exact. Of these people, 120 members would then be appointed to “working committees” to make laws in Sacramento. To accomplish this, Cox has committed to spending a million dollars of his own money to support NASCAR and set the stage.

“[NASCAR] is not going to make a difference just by itself, but it will get the public agitated and interested in reform,” says Cox.

“The reform we’re talking about is the ‘Neighborhood Legislature,’” he continues. “It’s not about expanding the Legislature; it’s about shrinking the size of districts and getting money and influence out of the picture.”

Multiplying the number of state representatives, he argues, will remove the incentive for donors to throw around as much money. Votes would be diluted and influence would dissipate. It would also make Sacramento a joke and completely unmanageable, according to a few of the individuals who cast votes.

“We have campaign disclosure,” Assemblyman Gordon says, “so to have somebody wear a uniform is pretty ridiculous.”

The attention being paid to NASCAR could be a new starting point for Cox, who admitted he might have an interest in running for governor after his current initiative. And after shaking up the Statehouse, of course.

“You ask me if I’m going to run for governor,” Cox says, his voice rising. “I’m going to change the Legislature.”

‘Clean suit’

The Voters’ Right to Know Act is a serious-sounding ballot initiative because it is. It intends to amend the state constitution by adding language about campaign finance disclosures. Crafted with the help of Bob Stern, the godfather of political reform in California, and Gary Winuk, the former chief enforcement officer for state political watchdog the Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC), the measure offers substance over form.

It would prohibit lobbyists from handing out gifts to legislators, revise the rules on how big donors are disclosed in ads, double penalties for violations of the state’s Political Reform Act and update the state’s database to better track the way money flows between candidates and political action committees, or PACs.

Despite collecting more than 146,000 signatures—25 percent of its goal—as far back as February 9, the biggest opponent to Voters’ Right to Know might not be special interests or shadow organizations affiliated with the Koch brothers, but other government reform initiatives like NASCAR. Competing measures often make it more likely that all proposals, even those with actual teeth, will fail.

Stern, who co-authored California’s Political Reform Act in 1974, called Voters’ Right to Know “the most significant” effort to police political contributions since the state’s landmark legislation more than 40 years ago.

Billionaire GOP activist Charles Munger Jr. is also pushing a constitutional amendment to make the system more transparent. Titled the California Legislature Transparency Act, the initiative would require the language of all bills to be finalized 72 hours before a vote is taken, preventing any sneaky late additions; make all floor sessions and committee meetings available online within 24 hours; and allow anyone to video-record these meetings, which is currently a misdemeanor.

“I would recommend this for all states,” Munger, a Stanford alumnus, recently told the school’s newspaper. “It’s time for all state legislatures to join the 21st century.”

Cox says he and Munger have met and discussed ideas to reform the state’s political system, but it doesn’t sound like the two saw quite eye to eye.

“I was president of the Cook County Republican Party,” Cox says. “I don’t take a back seat to any Republican.” In regards to Munger’s constitutional amendment, he adds, “It’s not going to move the needle.”

It’s that kind of talk that makes a Republican like Cox, who says he is anti-Trump and respectful of unions like the one that his schoolteacher mother was a part of, tough to pin down. He decries “cronies” and purchasers of political influence and then recommends a Washington Post op-ed—written by Charles Koch—that disingenuously laments a government designed to advance the interests of the nation’s wealthy elite.

As part of his NASCAR campaign, Cox has created 121 cardboard cutouts—one for every state legislator and Gov. Jerry Brown, who is one-third bigger than the rest. The ease with which Cox can explain the idea and the familiar acronym make it a humorous proposal to pitch to journalists and voters on the street. There aren’t too many people who would pass up a chance to dress down politicians by making them dress up in donor logos.

“This is a means to an end,” Cox says, “and we’re doing this to ridicule the system. I hope what happens is everybody walks into the legislature with a clean suit.”

Or an ugly one.

When the realtor hits the road

If the North Bay delegation to Sacramento were a NASCAR driving team, the four elected officials it comprises would be wearing big patches to indicate that the California Association of Realtors has been a major sponsor of their respective races. The powerful lobby—one of the largest in the state and a subsidiary of the National Association of Realtors—has contributed a total of $60,200 to the four elected officials from our area in recent elections. Does the organization wield influence over these pols? You be the judge. Last year, a bill sponsored by Sen. Mike McGuire that would have pushed out a statewide regulatory scheme for the growing vacation-home-sharing economy was pulled after the association demanded that the real estate agents it represents be eliminated from its regulatory reach.—Tom Gogola

District 4 Assemblyman Bill Dodd

California Association of Realtors: $16,400

California State Association of Electrical Workers: $16,400

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Local 2881: $12,300

Sheet Metal Workers Local 104 District 2: $12,000

State Building & Construction Trades Council of California: $8,200

American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees: $8,200

California State Firefighters Association: $8,200

District 10 Assemblyman Marc Levine

California Association of Realtors: $16,400

California State Council of Laborers: $16,400

Northern California Carpenters Regional Council: $9,035

California Correctional Peace Officers Association: $8,200

Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians: $8,200

Western Manufactured Housing Communities Association: $8,200

Domestic Workers Local 3930: $8,200

District 2 Sen. Mike McGuire

California State Association of Electrical Workers: $16,400

California Teachers Association: $16,400

California Association of Realtors: $15,400

AFSCME District Council 57: $12,800

California School Employees Association: $12,000

Operating Engineers Local 3: $10,000

Northern California Carpenters Regional Council: $9,595.20

District 3 Sen. Lois Wolk

California Association of Realtors: $12,000

California Teachers Association: $11,400

State Building and Construction Trades Council of California: $11,000

California State Association of Electrical Workers: $11,000

California State Council of Laborers: $10,4000

Northern California Carpenters Regional Council: $9,000

Time Warner Cable: $7,800

Data assembled from VoteSmart and the National Institute on Money in State Politics.