By Charles Brousse

Last week’s newspapers carried notices that Angela Paton had died in Los Angeles of complications from a stroke. She was 86 years old. I didn’t know Paton personally, but I met her several times and reviewed a number of plays she was associated with as a leading Bay Area actress, director and producer from roughly 1966 to 1991, when she moved to Southern California.

In retrospect, those 25 years were quite extraordinary for both theater artists and their audiences. Prior to 1966, most of the excitement was generated by touring productions of hit Broadway shows that had either closed their original New York runs, or were about to shut down. The only locally based group that competed significantly against these invaders was San Francisco’s semi-professional Actor’s Workshop, which turned out surprisingly good productions, but lacked the resources to attract a large following.

All that changed with the 1966 arrival of a jolly band of performing artists from Pittsburgh who quickly assumed the rather grandiose title of the American Conservatory Theatre (A.C.T.). Sponsored by a cabal of San Francisco’s richest boosters, it had the venues—the ornate Geary Theater, just off of Union Square, and the underused modern Marines’ Memorial Theatre, a couple of blocks up Mason Street. It had the money to pay professional actors, costume them appropriately and build handsome sets for them to work on. Most importantly, it had Bill Ball, one of the most flamboyant and visionary cultural leaders this country has ever produced, as its leader.

Almost overnight, Ball dazzled the region with the troupe’s energy and virtuosity. His formula was as simple as it was effective: Select great plays from Western theater history, mix them with the best of modern American writing, give each production a fresh, easily recognizable, muscular style presented by a resident company of talented actors and designers whose names would become embedded in the public’s mind as being associated with the highest quality and package the whole thing with razzle-dazzle public spectacle (criss-crossing searchlights and liveried musicians playing fanfare trumpets outside the theaters at openings.) It was ingenious and it worked!

That was the environment in which Paton, then in her mid-30s, came to work. As one of the company’s leading ladies from 1966 to 1972, she took on a number of memorable roles, including an unforgettable Mary Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Olga in Chekhov’s Three Sisters and the juicy character part of Lady Bracknell in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (among others).

By the early ’70s, the Bay Area’s theatrical landscape began to change again. While still dominant, A.C.T. gradually lost its unchallenged prominence as growing nonprofit regional companies in San Jose, the Peninsula and the East Bay made their bids for subscribers. At first, they still offered seasons that resembled A.C.T.’s. Berkeley Rep, for example, gave Paton the opportunity to take on major roles in works by Shaw, O’Neill and Shakespeare, but gradually their seasons—and the seasons of the many smaller theaters that sprouted up beside them—began to reflect the decline of Broadway and the emergence of a new play movement that featured works by young writers that practically nobody had heard of, performed by young actors who were similarly unknown.

In an effort to maintain quality while giving voice to these trends, Paton and her UC Berkeley drama professor husband Robert Goldsby, founded the Berkeley Stage Company in 1974, which for 11 years distinguished itself for intelligent programming and effective low-budget productions. Sadly, however, the glory days were over. The great plays and great roles were no more and Paton moved on to movies, TV and the occasional performance in theatrical venues elsewhere.

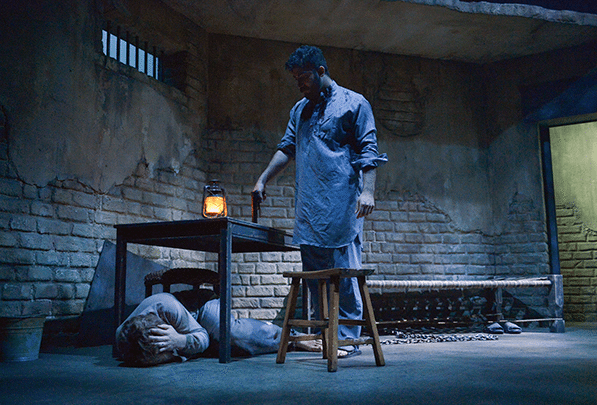

In today’s environment I sometimes grieve for what we have lost. Would an Angela Paton find a place today? But then I see plays like The Invisible Hand at Marin Theatre Company, or Master Harold … and the Boys at the Aurora Theatre Company, both of which deal masterfully with the kind of urgent socio-political issues that rarely were part of theatergoing when the classics ruled, and I’m comforted by the thought that the situation isn’t so bad after all.