Employees of one of the North Bay’s largest healthcare providers are fighting against service cuts which could impact patients from cradle to grave.

According to its website, Providence operates 52 hospitals across five western states. In the North Bay, it owns three hospitals and provides birthing and hospice care to hundreds of patients a year.

Recently, citing nationwide worker shortages, the nonprofit healthcare giant has begun cutting back on local services. Last month, Providence announced plans to close a birthing center in Petaluma, the only such facility between Santa Rosa and San Rafael. Three months earlier, with less public outcry, the nonprofit fired about 15 hospice workers and shortened the length of health aides’ visits with patients from 90 minutes to 60 minutes.

In recent weeks, the cuts—both enacted and proposed—have been met with resistance both inside and outside Providence.

Birthing Center

In January, Laureen Driscoll, chief executive of Providence’s Northern California region, sent a letter to the Petaluma Health Care District, a public agency which sold the hospital to a Providence subsidiary in 2021. Driscoll explained that, due to staffing struggles, Providence intended to close the Family Birthing Center at Petaluma Valley Hospital, consolidating services at its Santa Rosa hospital.

“Despite the best efforts by Providence and the local physician community to support the Family Birthing Center at Petaluma Valley Hospital, recruit new physicians and secure anesthesia services, it has become clear that the program cannot continue to sustain itself and meet our high standards of safety and patient experience in the coming years,” Driscoll wrote in part.

The letter prompted swift pushback from the community, workers and the district. The district maintains that, in a contract signed at the time of the sale, Providence agreed to keep the birthing center open until Jan. 1, 2026.

In a public statement in January, health care district CEO Ramona Faith wrote, “Contrary to a statement issued by Driscoll that Providence is working with the District to ensure a smooth transition, the District Board has not agreed to this outcome or made a decision… Per the [Petaluma Valley Hospital] sale agreement, the closure of the Family Birthing Center without the approval of the majority of the Directors of the District Board will be a default under the agreement.”

If the Petaluma birthing center is closed, it will create a 41-mile gap between similar service centers in Santa Rosa and San Rafael.

Despite public pressure, at a tense public meeting on Wednesday, Feb. 15, Driscoll told district board members that Providence planned to continue with its plan.

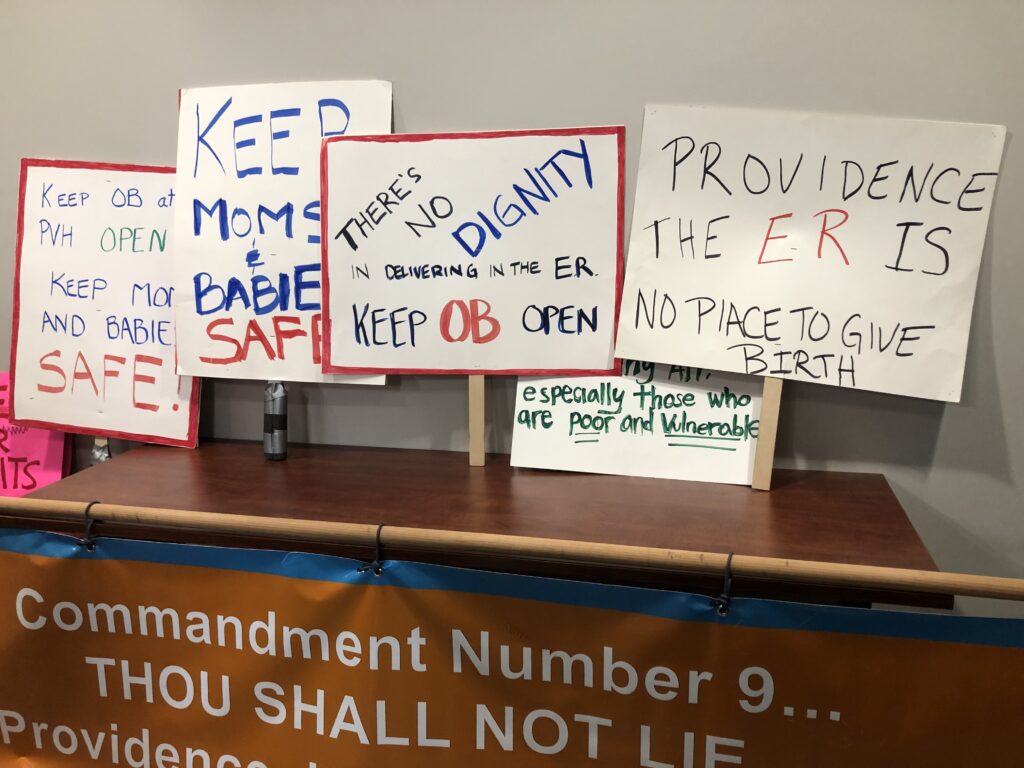

At a curb side rally before the meeting, workers and supporters from the community waved signs condemning the closure plan.

“They’re saying that they need to close because they can’t find anesthesia coverage but, if they would pay market rate, it would not be a problem finding coverage,” said Denise Cobb, a labor and delivery nurse who has worked at the Petaluma Valley Hospital for 25 years.

Janice Cader Thompson, Petaluma’s vice mayor, joined the protest as well.

“Women’s health is on the line in the United States and I want to make sure that, in my hometown, women are able to get the services they need. Not having an OB ward is dangerous for the mother and the child,” Cader Thompson said.

Though critics aren’t convinced, Providence has maintained that closing the birthing center, which it says lost over $900,000 in 2021, is not a financial decision. Instead, the nonprofit cites safety concerns brought on by pandemic-fueled staffing struggles.

At the district meeting, Driscoll revealed that Providence had received two responses to a Request for Proposals seeking help continuing to provide obstetric anesthesia coverage in Petaluma. Driscoll said staff are still evaluating the documents, some of which were received the day before the district’s meeting.

District board members took turns criticizing Providence’s plan and the way it was announced. After reading Providence’s response to questions from the district, board member Dr. Jeffrey Tobias said, it did not seem that the healthcare provider was trying its hardest to keep the birthing center open.

“I did not walk away from the response getting the sense that there was any willingness to maintain the services… and the discussion about collaborating with the district is [about] collaborating to close the unit. There’s really been no attempt to collaborate [on keeping the center open] so far—hopefully we can moving forward,” Tobias said.

After a closed-door discussion, the board announced that it had voted to reject Providence’s request due to a lack of evidence of “meaningful efforts to solve the lack of anesthesia services.” The board also created an ad hoc committee to work with Providence to keep the birthing center open.

As of the end of the week, it remained unclear how Providence would respond. A spokesperson declined to comment on the board’s vote, instead providing a letter to the editor by Driscoll published in the Press Democrat on Feb. 5.

Hospice Care

While workers at Petaluma Valley Hospital help to usher babies into the world, other Providence employees work to keep North Bay residents comfortable in the last months of their lives.

In 2021, hospice workers cared for 1,375 patients, a federal report filed by Providence states. Most received services at their homes scattered throughout Sonoma County, along with a few in Marin County.

Aidee Garcia, a home health aide who has worked at Providence for six years, says the demanding yet rewarding job involves a combination of “physical, mental and emotional work.”

“Some of the patients, they don’t have family around or they don’t have any relatives, and we are the only ones who come to see them,” Garcia said.

In October, employees received a series of disheartening announcements from management. First, workers were informed that in-home health aides would be required to serve five patients per day, a 20% increase in workload, requiring aides to spend 30 minutes less per patient.

Two weeks later, management fired around 15 employees. Hospice workers say the unceremonious layoffs impacted a range of support workers, causing a chaotic reorganization.

But, instead of taking the cuts lying down, workers used them as motivation to unionize. On Thursday, Feb. 9, despite opposition from Providence, hospice employees voted 105-6 to join the National Union of Healthcare Workers, which already represents many workers at Petaluma Valley Hospital.

Asked for comment on the impact of cuts and union campaign, a spokesperson stated that “Providence is committed to ensuring we continue to provide the level of hospice services at the bedside that every patient needs and their family is counting on at a sacred time in their lives.”

The nonprofit opposed the union campaign because “We believe that we can better work out issues and resolve caregivers’ concerns when we work directly with each other. However, we respect the right of caregivers to explore union representation and the decision our hospice caregivers have made to join a union,” the spokesperson stated.

In an interview, Garcia and three other workers said their concerns about the impacts further cuts would have on patient care fueled the union campaign.

“One of my patients said, ‘When you come, you bring me love,’” Garcia said. “I feel like we’re not losing that love because it’s something that we have [inside], but I feel like Providence [by cutting back] is going to take away our ability to protect our patients the way we used to.”