When Damon Evans was adding yet more martial arts to his arsenal of fighting systems—in this case, the Filipino discipline known as Kali and the Thai style known as Muay Chaiya—his maestros kept telling him his timing was off.

Not in his moves, but when he was born. He should have lived several centuries before, they said, when he could have become a legendary warrior.

Evans is nevertheless in charge of his destiny even in these modern times, when keeping the torch of tradition burning is actually even more important than it was in the ages of Vikings, Vandals, Mongols and Huns. Born under the sign of Aquarius—the bringer of water, typically symbolizing knowledge—these days Evans thinks of himself more as a scholar of martial arts than a warrior. Having a daughter tends to soften your outlook, he says.

In 2001 Evans founded The Academy of Jeet Kune Do Sciences in Petaluma, where he offers classes and private lessons for kids and adults in a dizzying variety of martial arts styles, including Muay Thai, Kung Fu and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, plus ones few have heard of, such as Savate, Silat and Pananjakman. The mental benefits from martial arts training are incalculable, so for those ready to change their lives, beginner classes are held Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 6–8pm.

Membership runs around $150 per month, and Evans recommends training at least twice per week. After 12–18 months students will have graduated from phase one, and will have a sense of accomplishment no one can ever take from them. From there, it’s merely a question of how high they want to go.

As for the name of the studio—The Academy of Jeet Kune Do Sciences—well, that’s what’s at the studio’s core—that core, of course, where chi, or life force, is concentrated. It also has a Bay Area tie-in, as Jeet Kune Do is Cantonese for “way of the intercepting fist,” and is the system developed by Bruce Lee, the movie star and martial artist who was born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1940.

Lee began his martial arts studies in Wing Chun Kung Fu, but in 1967 decided to break with the centuries-old tradition and develop his own hybrid fighting style that emphasized simplicity and practicality for self-defense in real-world situations. He called it “the style of no style.”

But that doesn’t mean there are no ingredients. JKD, as it’s called for short, combines elements of western boxing with kung fu, but Lee’s real innovation came from fencing, which he learned from his brother.

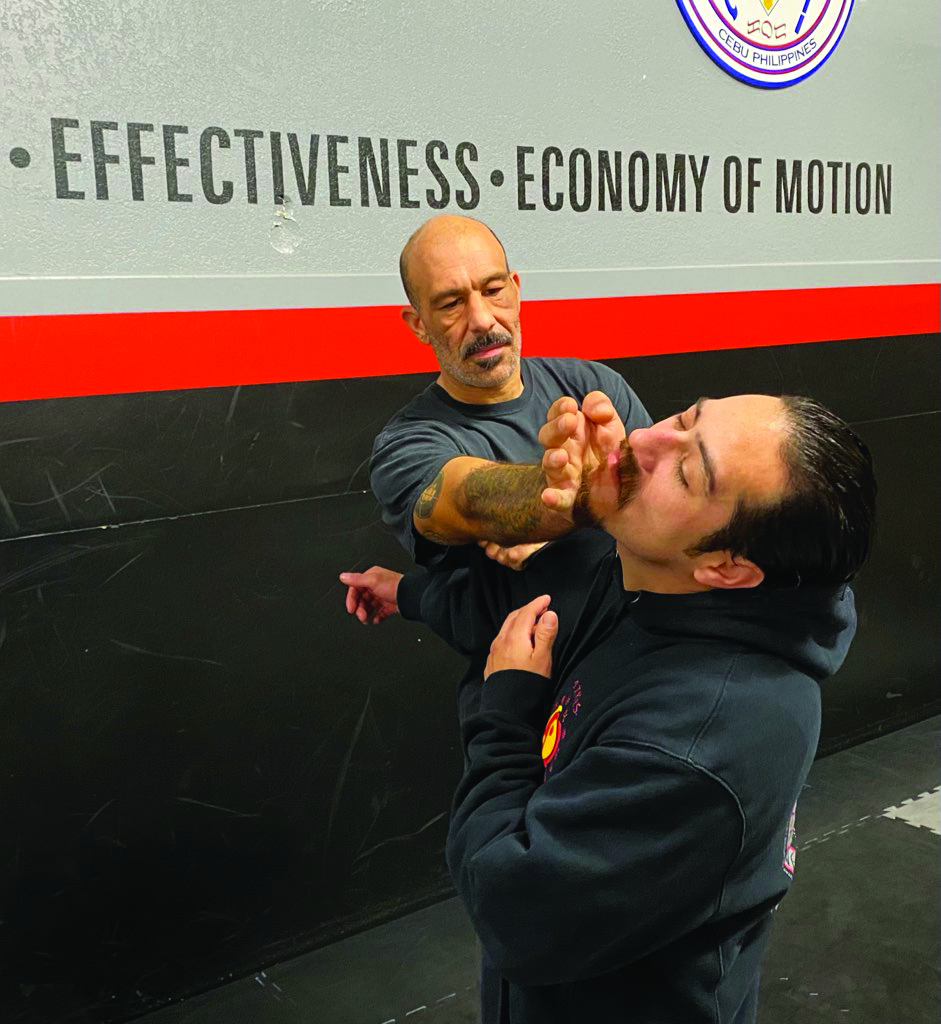

Instead of standing square to the opponent as in kung fu, or with the weaker, jabbing hand in front and the strong one in back, as in boxing, Lee applied a wide, side-on fencing stance with his strong “weapon” hand in front. It puts a fighter’s naturally dominant hand in front to take control of a confrontation. It is the closest to the opponent and will do the most work—blocking, grabbing, gouging. But, most importantly, it is poised with every heartbeat to deliver a straight, fast and accurate “intercepting fist,” or what in fencing would be called a stop-thrust.

The fencing stance also put Lee’s dominant leg in the front, for quick kicks to the opponent’s front knee. In the spirit of science, JKD is said to be comprised of 60% kung fu, 20% boxing and 20% fencing. For Evans, it is the best and most practical foundation for self-defense, and much of what is taught in militaries around the world is some form of watered-down Jeet Kune Do.

Never doubt the power of just a little bit of training in dealing with a belligerent jerk in a bar, even a bigger guy who’s liquored-up. In general, skill will beat strength, Evans says. However, technique will beat mere skill, and tactics—or a dynamic, strategic approach to confrontation—will beat technique. At the very top of the pyramid is a force that cannot be taught. Call it adrenaline, rage or the will to self-preservation. Evans simply calls it “indominable spirit,” saying that when it comes to that, “Nature has already given you everything you need.”

The 2021 pitch to finally take up training is really no different than at any other time, Evans says. The world is always uncertain and fearful, and confidence and capability do much to assuage that. “This stuff is life changing and life saving,” Evans says, “and that’s really all there is to say. There is the closest to reality you’re going to get. There is nothing more realistic than combat.”

Martial arts also develop and heighten our sense of awareness, so that we cease going through life dazed and lost in thought—or lost in phone—and make us acutely aware of living in the moment, knowing that a freak car accident or entering a store at the the same time as an armed robber is always a possibility, however remote. “You learn unpredictability in martial arts, because that’s all life is,” Evans says. “The reason you train is because you never know what will happen.”

One person who learned this first-hand is Evans’ most special student: his son. One would think that growing up with a dad who’s a martial arts instructor as opposed to, say, a math teacher, would be a young boy’s ideal, but not Evans’ son, who partook of his training begrudgingly and showed no great like or dislike for it.

Then one night when he was 20, while out with friends, they were confronted by three thieves—one of whom was armed with a knife—who demanded their wallets. Everyone anxiously complied save for Evans’ son, who simply stood his ground and said, “No.” This simple defiance was enough to convince the thieves not to mess with him, to nod their respect and go on their way.

Afterwards, son approached father and expressed his gratitude, thanking Evans for all the skills and courage he’d instilled in him as a boy. It had finally paid off, and without even having to throw a single intercepting fist.