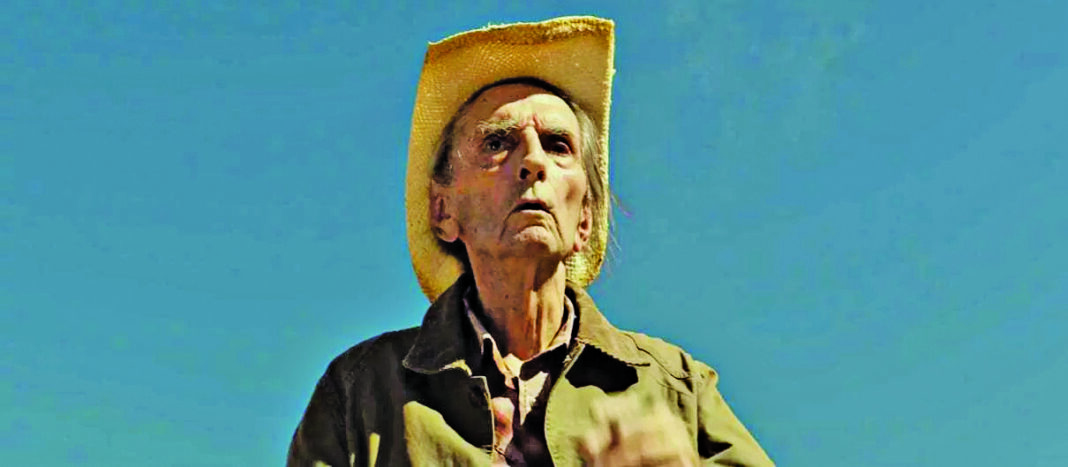

Harry Dean Stanton, who died in September, was something better than a movie star, a character actor with some 60 years of credits. Lucky isn’t the last of Stanton, but it’s likely the last best view we’ll get out of the actor, who, at the end looked like an outsider artist’s statue of Abe Lincoln carved out of cypress wood. Director John Carroll Lynch follows a week in the life of the 90-ish Lucky—he got the name back in the Navy, since he had the cushy job of a ship’s cook. The old man has a place out in the desert not far from the saguaro cactuses, and he follows an undemanding schedule: Exercising in his skivvies, making some coffee from a machine that keeps blinking “12:00” in fiery red letters and tottering on downtown to get some cigs and some chat at the diner. At night he goes for a couple of rounds at a local bar.

There are barfly movies of the Charles Bukowski vein—this one’s more of the William Saroyan vein; lots of harmless backtalk, but nothing fisty.

Lucky wanders, yet the movie seems tight and full of purpose. He exchanges war stories with a Marine (Tom Skerritt), goes off to a Mexican birthday party where he sings a song for the mariachis and sticks his head in a pet shop, where he mulls over that common pet-store expression, “Forever home.” He mentions his fear, his old guilt, but there’s no slowness in his stride as he walks right past a church. Lucky is about the importance of recognizing mortality, nodding at it and going on your way.

This movie is a thing of beauty. It’s said that it was hard to tell how much of Lucky was Stanton or the other way around, but it’s a seamless performance, free of codgerisms. It’s the kind of late-period acting Clint Eastwood tries to do. It’s poetry, and it has a point: What’s the purpose of being a tortoise, or obtaining great old age? Is there a better one than simply being a living lesson to everyone to calm the hell down?