by Matthew Stafford

Scores of writers, historians and folklorists have contributed to the enduring legacy of the fairy tale. Here’s a who’s who of the genre’s most significant personalities.

Giovanni Francesco “Straparola” (1480-1557), “the father of the literary fairy tale,” was the first European straparola (scribbler) to write down the fantastical folktales that had been told and retold for centuries. His magnum opus, The Facetious Nights of Straparola, features 75 bawdy, heroic, fantastic stories ostensibly shared over the course of a 13-day wingding, including 15 that we’d define today as fairy tales. Published in 1550 (and banned by the Catholic Church 74 years later), it includes the earliest known versions of Puss-in-Boots and The Golden Goose.

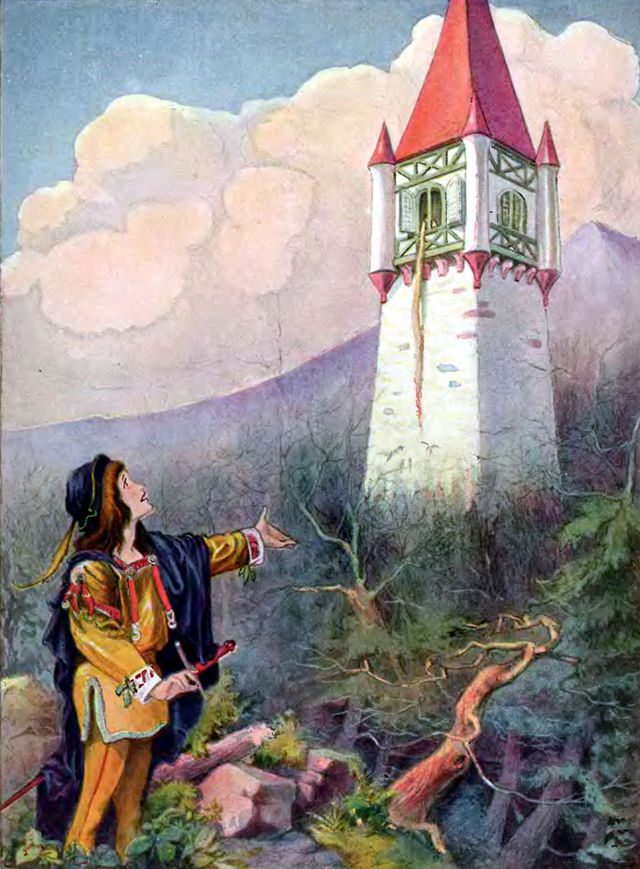

Despite a successful career as a poet and courtier, Giambattista Basile (1566-1632) is remembered for the two volumes of fairy tales he collected and that his sister published under a pseudonym after his death. The Tale of Tales contains 50 stories (including early versions of Rapunzel, Cinderella, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty) written in Basile’s baroque Neapolitan prose (“the Sun with his golden broom swept away the dirt of the Night”). Neglected for two centuries, it was rescued from obscurity by the Brothers Grimm, who praised it as “the first national collection of fairy tales.” (A movie version of The Tale of Tales starring Salma Hayek is due for release later this year.)

Charles Perrault (1628-1703), a favorite in the court of Louis XIV, lifted the fairy tale from its folksy, rustic origins and made it palatable for the aristocrats of Paris’ literary salons. His Tales and Stories of the Past (better known by its subtitle, Tales of Mother Goose), written after a long career as court poet, cultural arbiter and advisor to the Sun King, took the simple plots of Basile, Straparola and their Roman and medieval predecessors and modernized and embellished them with local color, Versailles gossip and a witty, sardonic tone. His stylish reinterpretations of Little Red Riding Hood, Sleeping Beauty, Blue Beard and Cinderella have earned him the title, “The founder of the modern fairy tale.”

The life’s work of Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) Grimm was to research and preserve German language, culture and folklore, and along the way they published Children’s and Household Tales, a scholarly tome of 86 stories of rigidly Germanic origin. Six revised editions and an additional 125 stories later, it formed the template for the fairy tale as we know it today. Gathered from peasant and aristo alike, and reworked and embellished with plot detail, psychological motivation and spiritual subtext, the tales were dark, violent “warning stores” for misbehaving children—a far cry from Perrault’s saucy adults-only fare. The brothers, who rejected the salonnieres’ high literary style for the regional dialects and “Low German” of the common Volk, brought fairy tales like Rumpelstiltskin, The Frog Prince and Hansel and Gretel to a whole new audience.

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) was the first of the fairy tale scribes to come up with his own stories instead of collecting them from earlier sources. A prominent Danish novelist, poet and travel writer, his first two volumes of Fairy Tales were unsuccessful—until they were translated into several languages in 1845 and The Little Mermaid, The Snow Queen, The Ugly Duckling, The Emperor’s New Clothes, The Princess and the Pea, Thumbelina, The Fir Tree, The Little Match Girl and The Red Shoes made him a famous and beloved figure around the world. (This despite the frequently somber tone of the stories—a tone inspired, perhaps, by Andersen’s miserable childhood and rumored lifelong celibacy.) International Children’s Book Day is celebrated on his birthday, April 2.