Two months passed quickly for the homeless people living in a city-sanctioned encampment at Novato’s Lee Gerner Park.

At a Feb. 11 meeting, the city council voted to close the camp, giving the seven remaining residents 60 days to relocate.

Despite Marin County’s recommendation that Novato allow the campers to stay and continue on a pathway to housing, the city scheduled the camp closure for April 19. Adding insult to injury, the city council also recently approved an ordinance making it a misdemeanor to camp on public property.

The homeless residents were obviously concerned about their future after the vote to close the camp. However, city officials repeatedly said that staff would use the 60-day period to work with the county and service providers to expedite getting the residents into shelter or housing, leaving the campers somewhat optimistic.

Either city officials were being disingenuous in pacifying the homeless community and their advocates, or they were simply ignorant about the process of getting people off the streets.

None of the seven homeless people received a shelter bed or housing.

Novato’s failure is particularly bitter because it had great success with the Lee Gerner Park encampment, which served as a staging ground for homeless people to obtain housing and services.

County data indicates that 28 people from the camp were housed, while the Marin Homeless Union maintains that another dozen received housing before the city officially sanctioned the camp in October 2022.

The 60-day deadline was arbitrary and inadequate, especially with Marin’s short supply of shelters and housing vouchers. There’s virtually no way to speed up the process.

“Our shelters remain at capacity,” said Paul Fordham, Homeward Bound CEO. “Whenever we have openings, they are filled very quickly. We receive at least 25 requests for each bed that comes available, so we can never guarantee that anyone will get a bed.”

And Marin County staff were already working with Lee Gerner Park residents to secure housing. Did Novato think the county could wave a magic wand and make housing appear?

“The County has always been fully engaged with this group of clients,” said Gary Naja-Riese, director of Marin’s Homelessness & Coordinated Care department. “All seven clients are engaged with services. Some have housing-based case management and are on a housing pathway; others are working with Outreach on Rapid Rehousing or other housing pathways. The County will continue to work with them regardless of location.”

Exactly what did the city do to help the seven homeless people in those last 60 days? The Pacific Sun posed this question to city manager Amy Cunningham and the council members. Not surprisingly, they clung to the same tired rhetoric.

“During this time, the City continued to work closely with local service providers to assess each camper’s individual needs and offer case management services, connecting them with the most appropriate available support, including housing and shelter services,” Novato spokesperson Sherin Olivero wrote in an email.

Fail. Several campers were never offered a case manager. Again, housing case managers are in short supply.

Olivero also said the “campers voluntarily vacated Lee Gerner Park prior to the conclusion of the 60-day delayed enforcement period,” seeming to suggest that they may have received something more than a police escort out of the park if they had waited a few more days.

Yes, the camp residents left voluntarily. As eviction day drew near, they became anxious, fearing the police would clear the camp and seize their belongings. To avoid the trauma of a sweep, they decided to leave the weekend before the April 19 cutoff date.

Volunteers brought in a U-Haul early on Sunday morning. The campers did not want to leave their home. Lee Gerner Park represented hope for the future—housing and dignity.

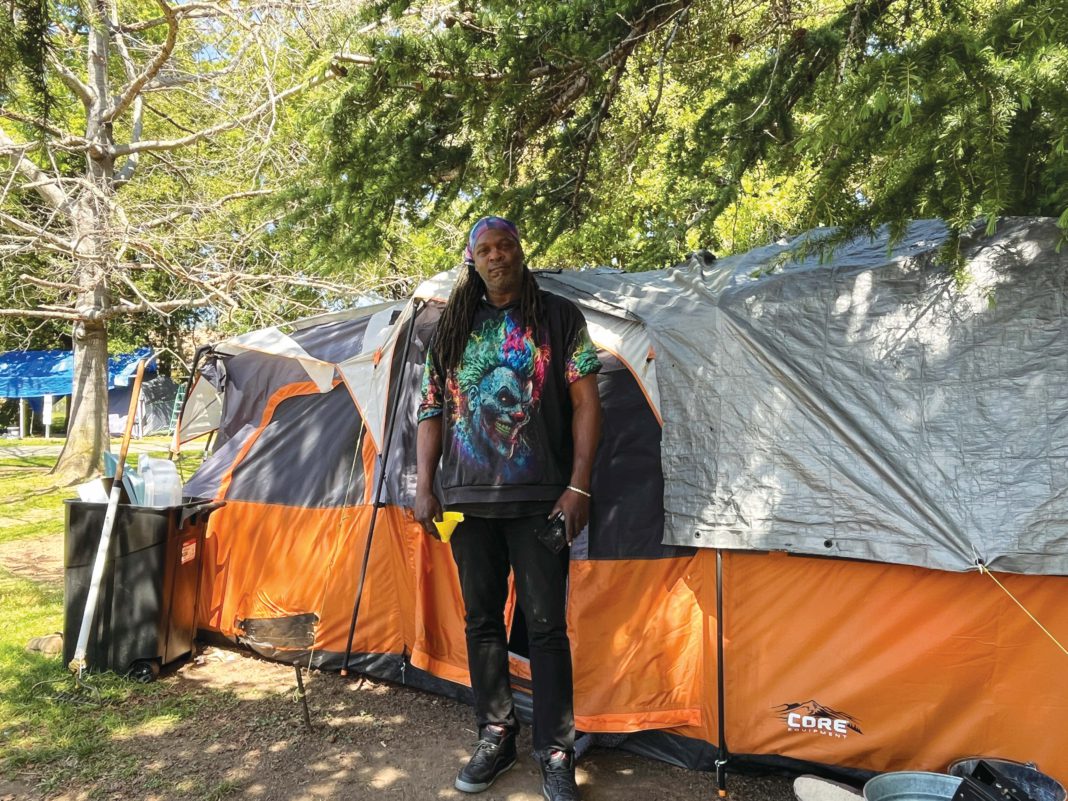

“I’m not really happy about it,” said Michael, a camp resident, as he cleared out the last of his belongings. “They want to get us out of the public eye. I don’t even have a case worker, and I’ve been living here for a year. They make me feel like I’ve done something wrong. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

Charles, another park resident, expressed similar feelings while he dismantled his tent. Mostly, he was sad to leave because his children live nearby.

“It’s very peaceful here,” Charles said. “People in the community donated food and clothing. We had a good rapport with them. The way people treated us, it made us have a sense of security. I’m scared now. I don’t know the law or my rights, and I’m disabled.”

Yet, they packed up their belongings and placed them in the moving truck. Then they cleaned the campsite thoroughly, even raking the dirt.

Volunteers and the campers took away the first load. Back and forth they went, until every camper and item made it to a new spot at an undisclosed location in Novato.

They’re trying to fly under the radar, for the most part staying away from public view. Now, community members don’t know where to bring donations of clothes, food and bedding—an unintended consequence.

Jason Sarris, who established the Lee Gerner Park camp and eventually received housing, spends numerous hours each week helping the seven homeless people. With his lived experience, Sarris understands the campers’ uncertainty and fear.

“We’re worried about the city enforcing its ordinance against camping in public and forcing them to move again when there’s really nowhere for them to go,” Sarris said.

Even the camp’s eldest member, a 73-year-old disabled woman, can’t get into a homeless shelter. Homeward Bound turned her away because of incontinence, according to a volunteer assisting her. Fordham of Homeward Bound explained there are several reasons why its two shelters, Jonathan’s Place and New Beginnings, can’t accept people with incontinence, including a small staff-to-client ratio.

“We are not able to accept anyone in our shelter programs who is incontinent unless they are willing and able to wear adult diapers and change and dispose of those diapers independently, without soiling bedding or furniture,” Fordham said. “We recognize that Marin needs resources for people who cannot meet these criteria, but we are not licensed or funded to provide this level of care and cannot safely support such clients.”

Resolving homelessness will take time—the one thing that Novato has refused to provide. For the seven campers forced to leave the security of Lee Gerner Park, it’s been devastating.

“They want housing, and they’re doing everything required to get housing,” Sarris said. “I just pray that the city will allow our camp members to go through the county’s housing process without getting swept or criminalized for being unhoused.”

Donations of bedding, clothing and non-perishable food for the former Lee Gerner Park campers may be dropped off at the Housing For All booth at the Downtown Novato Community Farmers’ Market, which is open from 4-8pm every Tuesday.

Great article Nikki! I met the campers before they moved out of the park. I was particularly impressed by the care, connection and compassion they had established with each other. It was a pleasure to spend a little time getting to know a few of them. It’s clear to me that the city of Novato was harsh and lacking in any real compassion in their ruling and that we as a wealthy county can do much better to insure a pathway to housing for all who need it!

I see red when I read this and it’s because there’s only one reason why the City of Novato has broken its agreement with the homeless and their advocates. It’s because of the relentless pressure put on them by the local anti homeless haters, who care not a whit where the unhoused folks go as long as it’s gone. These are people who think that Homeward Bound has no end of empty beds if only these lazy people who refuse to work, continent or not, who just want to engage in drug use and drinking all day and night, who “don’t want to follow the rules” would ask for one. The mint has been laid on the brocade pillow cases at the endless number of shelters with open beds here in the county awaiting their revered guests. There is a complete disconnect between what these “fiscal conservatives” think is available and what actually is. And no amount of educating them about the reality they refuse to see has opened their eyes to what just about everyone else knows. There’s no place for them to go. Yet all but 7 managed to find their way inside. Remarkable, when you think about it. But haters gonna hate and the facts be damned.

Nice try Nikki (or is it Jason?) you left out the part about 60 days with an additional 30 days if needed. You can listen yourself at the city council meeting on 2/11 at 3:04:10

Why did they leave early ? They had 30 plus days to stop being housing resistant and make some headway !

If the campers collectively decided to pack up the weekend before the “eviction”, which one of them designed and printed the “camp compassion in exile” flyer ? Willing to bet none of them

What’s an extra couple of days going to do ? Literally nothing. I’m not sure why you’re even bringing that up.

Public parks should not be used for homeless. How about empty buildings in San Marin.

Thank you, Novato City Council for preventing the inevitable spread of homeless blight that already infects huge swaths of Oakland and Berkeley, and that eventually destroys city after city. No one wants a “Mad Max” landscape here in Marin. Enough is enough!

A month is much longer than a couple days. Did you know God made the world in just 6 days ? I’ll throw my hat in the ring with a freebie for you : A 72 year old disabled person with no income qualifies for the medi-cal Aged and Disabled Federal Poverty Level Program that would allow them to receive SNF placement. A SNF is able to diaper for incontinence.

“I’ve been living here for a year. They make me feel like I’ve done something wrong.” as sad is it is to say. During that year you should have been working on making your life better, in anyway , not waiting for a case worker.

“I’ve been living here for a year. They make me feel like I’ve done something wrong. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

Maybe nothing “wrong” but what HAVE you done? One year of rent free living and you’ve managed to do what exactly? Society has a right to their public spaces. They are not campgrounds. It’s not your needs above everyone else’s, no matter how much you insist it’s how things should be. Instead of focusing on cities and towns for failing you (PS, they don’t owe you), why not write about corporations not paying living wages and thereby disincentivizing working for a living?

Sticks and stones: totally legit question here: what is an SNF?

Sunni Dezahed: They are as much “society” as you and me. These are your neighbors, not some unthinking, unfeeling commenters…oh….sorry.