On its face, California’s Brown family political dynasty is the story of two men, but metaphorically it’s really the story of three.

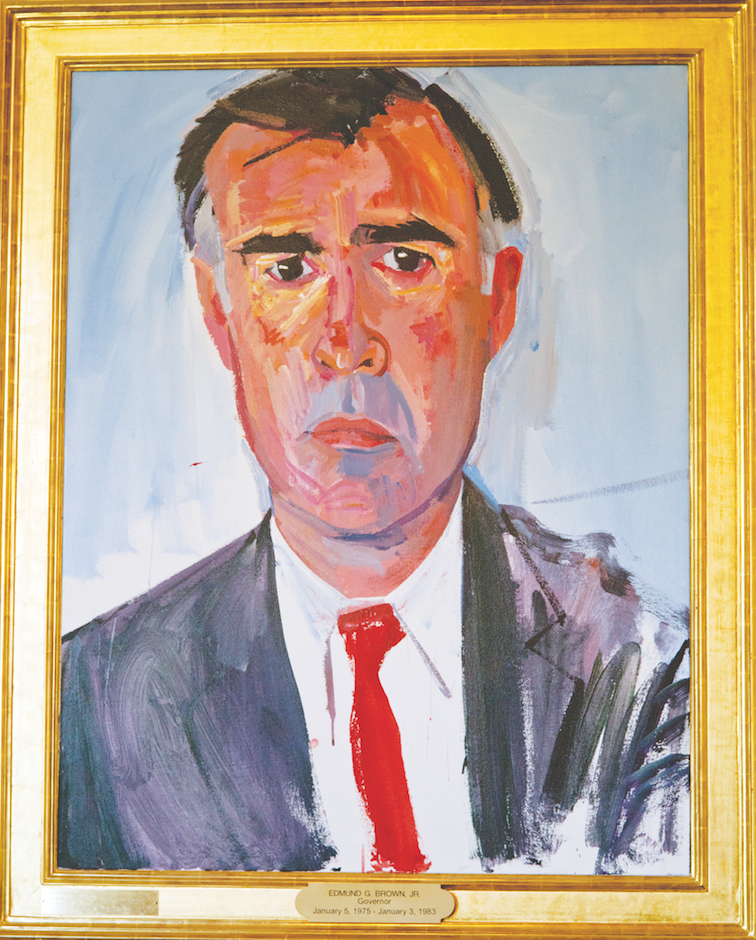

In the dialectical tale of the Browns, the thesis is Pat Brown, the buoyant old-school liberal who served as California’s governor in a time of expansion and optimism. Antithesis would be Brown’s brainy, aloof and austere son Jerry, who moved in to the governor’s office at the insufferable age of 36 with rock star Linda Ronstadt by his side, in a time of cynicism and retrenchment.

Then, in 2010, came synthesis, with the unlikely election of an older but wiser Jerry Brown, still the intellectually restless ex-Jesuit seminarian who, at the same time, had internalized much of the practicality and human touch that shaped his father’s career.

In a couple of months, Jerry Brown, at 80, is poised to step aside as California’s governor for the second time. As a narrative of political redemption, the Browns’ story is satisfying because it’s surprising. Back in 1983, when Jerry Brown’s first two-term stint as governor ended—brought low by Proposition 13, the Mediterranean fruit fly and his own reckless presidential ambitions—he was soundly defeated in a race for the U.S. Senate by Pete Wilson.

At that point, it looked like California’s relationship with the Browns was over. Today, at least to California’s majority Democrats, nothing seems more natural than Jerry Brown in Sacramento. Now, though, it’s almost a certainty that the Brown era is coming to an end in California. Jerry is both the only son in the family and childless, so at least the family name has reached the end of the line. It’s an ideal time for the intimately familiar story to be told in wide-angle grandeur. Journalist Miriam Pawel has risen to the occasion with her new book The Browns of California: The Family Dynasty That Transformed a State and Shaped a Nation (Bloomsbury).

The story of the Brown family almost exactly parallels the U.S. history of California. The family’s patriarch, German immigrant August Schuckman, arrived in California just a couple of years after statehood in the midst of the Gold Rush.

“I wanted to write a book that was a history of California as much as it was a biography, something that I thought would explain some of the unique and significant things about California,” Pawel says. “The family was a good vehicle to do that. I like to write history through people, and so this seemed to be a conjunction between an interesting and unusual family and an interesting and unusual state, and the impact and interplay that each one had on the other.”

Pawel, a Los Angeles Times reporter, fills in the colors of the Brown family with plenty of compelling secondary characters, chief among them Pat Brown’s freethinking mother and self-described “mountain woman,” Ida Schuckman Brown, who died at 96 the same year her grandson Jerry was first elected governor.

But mostly, Brown’s is a story of a father-and-son pair who provide an almost archetypal generational contrast, familiar to many who came of age in post-war America. Pat and Jerry Brown—that is, Edmund G. Brown Sr. and Jr.—were largely simpatico in political values. But in political styles, they could not have been more different.

Pat Brown was an engaging, exuberant, extroverted Hubert Humphrey–style liberal whose love of California was visceral and immediate. Pawel shows Pat’s enthusiasm for flying low in a propeller plane and gazing lovingly at the California landscape, and his habit of stopping in roadside restaurants to glad-hand potential voters. His upbeat personality reflected a kind of post-war optimism that guided him in initiating ambitious and legacy-building projects, particularly in the realms of higher education and water. Paradoxically, for a man considered the patriarch of a California dynasty, Pawel believes that Pat Brown has often been forgotten, especially considering his profound influence on the growth of California.

“It’s true that he’s been somewhat overlooked,” she says. “Part of that is the East Coast vision of California that he was a victim of, in some ways. There is one good biography of Pat Brown, and that’s it. And for someone who had such a major impact on the built environment of California—the water, the roads, the universities and the schools—it’s surprising there hasn’t been more exploration of his impact on the state.”

He was what is today an extinct American political species: the can-do liberal who dreamed big, then delivered. Along with educator Clark Kerr, the first Gov. Brown championed an ambitious master plan that turned the University of California system into the “model for modern research universities across the country,” with a commitment to keep the tuition free for all Californians.

Pat Brown also took on perhaps the state’s most intractable problem with one of its most ambitious solutions. Though the population of California was mostly in the south, the state’s water was mostly in the north. Early on, Brown declared a satisfactory solution to the water problem as “a key to my entire administration.” The result was the massive California State Water Project, featuring the giant aqueduct, now named for Pat Brown, that runs along the spine of California’s Central Valley.

In Pawel’s account, Pat Brown’s enthusiasms for governing California were charmingly sentimental. Brown was especially attentive to the moment when California surpassed New York as the nation’s most populous state. A billboard tallying the numbers was installed near the Bay Bridge, and when the moment finally came at the end of 1962, Gov. Brown declared a four-day celebration. Pat Brown also comes across as a proto-environmentalist who could not stay away from Yosemite and who said that his favorite spot in California was a High Sierra camp called Glen Aulin.

Brown was defeated for a third term by Ronald Reagan. After eight years of Reagan in Sacramento, turned off by the corruption of California favorite-son Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal, California turned again to an Edmund G. Brown, this time the son.

In contrast to his father, Jerry Brown—at least in his first term as governor, from 1975 to 1983—was more a reflection of the Vietnam-Watergate generation: arrogant, intellectually voracious, almost puritanical in his disdain for mainstream politics, the brooding iconoclast who simultaneously hated displays of wealth and loved hanging out with rock stars. Though it was never overt, young Jerry was a walking rebuke of his father’s entire orientation to the world.

Jerry Brown’s mission was to attack the status quo, and he often did so in the most theatrical ways imaginable. He canceled the inaugural ball, flew commercial, rented a small apartment while turning his back on the Reagan’s governor’s residence, and chose to drive a blue Plymouth instead of ride in the governor’s Cadillac limo. His staff, often called “the Brownies,” were a collection of friends and acquaintances, many of whom had no experience in politics. He had no chief of staff or other gatekeeper, and he often conducted the state’s business during hours only a vampire would keep.

Jerry’s style resonated in a post-Watergate era of limits, but it bewildered many of his constituents, not the least of which was his dad.

In interviewing many of Jerry Brown’s friends, Pawel says that many of them told her that “Pat never quite got Jerry. He was off dating Linda Ronstadt and sleeping on a bed on the floor and canceling the inaugural and all that. A lot of people thought it was for show. At the time, it happened to be good politics, but it also was a reflection of who he was. But I think his father was hurt by not being relied on, or let in more as an adviser. In fact, the worst thing you could do if you wanted to lobby Jerry Brown was to have his father intercede on your behalf.”

The last third of The Browns of California retraces Jerry Brown’s time in the political wilderness—the doomed 1992 presidential campaign, the stint at the head of the California Democratic Party, a gig as a talk-radio host. Pat Brown died in 1996, and the next year, Jerry announced his candidacy to be mayor of Oakland. In ’99, he took office in Oakland and experienced a political reawakening. Ironically, he found himself fighting laws that he had created as governor.

He vowed to bring 10,000 people to downtown Oakland. He got involved in potholes and karaoke permits. He was a common sight on the streets with his dog, Dharma. The move from philosopher king of Sacramento to pragmatic mayor of Oakland invigorated him.

The other X-factor that transformed Brown was Anne Gust, the retail executive who became his wife in 2005. Gust provided a counterbalance to his harsher political instincts. Oakland and Anne rounded off Brown’s rougher edges, according to Pawel, and made him more of a practical and effective politician.

In a remarkable turn of events to which we’ve all been witness, Jerry Brown then got a second bite at the apple, becoming governor again in 2010. Instantly he became a trivia question, as both the youngest California governor since the Civil War, and the oldest one ever.

Brown came into office ready to wrestle with the state’s chaotic finances and take on its dysfunctional penal system. He proved to be more moderate than many of his liberal supporters had hoped, but turned around a huge state deficit—thanks in large part to Democratic supermajorities and revenue-friendly ballot measures. Pat Brown didn’t survive to see his son’s second ascent to the governor’s office—the older Brown would have found the second Jerry Brown administration much more comprehensible than the first. But time has run out for Jerry Brown and the Brown family dynasty. He has mastered the art of politics just when it’s time to leave the stage.