By Maia Boswell-Penc

During the Senate Judiciary hearing on Sept. 27, Amy Klobuchar asked Supreme Court nominee—and now Associate Justice—Brett Kavanaugh if he’d ever blacked out or experienced memory gaps due to alchohol use—his response says it all:

“I don’t know, have you?” He angrily shot back at the Minnesota senator.

Kavanaugh’s non-answer and attempted table-turn is the answer to the inconsistency between Ford’s testimony and Kavanaugh’s.

Really, this was not a “non-answer”—it was an admission that Kavanaugh does not know whether he has blacked out or had memory gaps. He does not know, because he does not remember. He does not remember, because one does not remember blackouts and lapses of memory due to overconsumption of alcohol. One simply realizes that there are “gaps.”

I know, because I have been there.

My first blackout occurred my freshman year in college. I had come from an elite, single-sex high school in Dallas that was very much like the ones attended by Ford and Kavanaugh. I was woefully naive and accepted the cup of “trash-can punch” when it was handed to me, early in my freshman year in 1982.

The frat boy “bartender” came from an elite background similar to Kavanaugh, and he had it all planned out, I later learned, as revenge on me for having chosen to talk with a closeted gay guy a couple of weeks earlier during a “date” with him to a football game. The message was clear: “Ditch me for a gay guy? Rape is your punishment!”

While American society has made much progress on the heterosexism front, the same can’t be said of sexism. Women continue to be disbelieved, mocked, grabbed in their pussies without consent, while the perpetrators often remain in positions of power.

Acts of sexual aggression are not about sexuality; they are about power.

Kavanaugh can testify that the event described in painstaking detail by Ford (who told the committee she had consumed only one beer) “never happened” because, in his mind, it didn’t. He was too drunk to remember it. He threw the question back at Klobuchar, as though she was the one being questioned.

That is how it goes in a culture of rape. When the questioning begins, the victim gets grilled. As someone who is a survivor of rape—yes, on the night of the trash-can punch—and sexual assault, and as someone who has experienced blackouts and memory gaps from drinking, I understand completely how both Ford and Kavanaugh can be telling the truth.

That I was raped in the fall of my freshman year, 1982, the same year Christine Blasey-Ford endured her event, and that my experience occurred at the hands of a privileged frat boy from an elite family—I can still see in my memory his chunky gold Rolex watch—has served to bring back the terror, the anguish, the shame and bewilderment in vivid detail.

This is the case for countless women all over the country, as one out of every four women is a victim of sexual assault or attempted sexual assault. Bear in mind, only 2 percent of perpetrators are ever brought to justice. Though I am certain that the event that happened to me was instigated by grain alcohol—and though I do have memory lapses from that night—I also know with 100 percent certainty the name and face of my perpetrator. Harrowing events are often accompanied by memory impairment brought on by the trauma. Even if the victim’s memory is further impaired by drugs or alcohol, the parts that are remembered are key. We tend to remember some things in vivid detail while forgetting other things.

Trauma memories are very different from blackout memories. Trauma renders some pieces of an event in vivid detail, and allows others to fall away. It does not cloud our memories of the key details. Blacking out from drinking can do that. I know, because after being raped, my coping strategy at difficult times was to drink.

Ford may not have remembered how she got to the party, or how she got home from it. But she remembers with absolute certainty that Kavanaugh was the person who groped her, who ground his body into her, who laughed at her powerlessness, and who attempted to rape her. Her recollection of the cruel laughter of Kavanaugh and Mark Judge after the assault makes the point that this episode was all about power, and remains so.

In the midst of a presidency that is all about lies, deception, indecency and aggression toward women, a presidency that cozies up to powerful elites and strongmen, this is important. In the midst of a presidency that lacks integrity, courage, human decency and honor, that abandons allies, abandons innocent children and scars them for the rest of their lives by separating them from their parents, this is important.

The #MeToo movement is in full swing and the backlash continues to rear its ugly head, most notably in the face of an angry, spitting Lindsey Graham, who clearly finds this all too close to home. And in the face of an angry, accusing Brett Kavanaugh, dredging up partisan politics in an attempt to muddy the waters, to hide his shameful, drunken aggression toward women, and to claim his innocence.

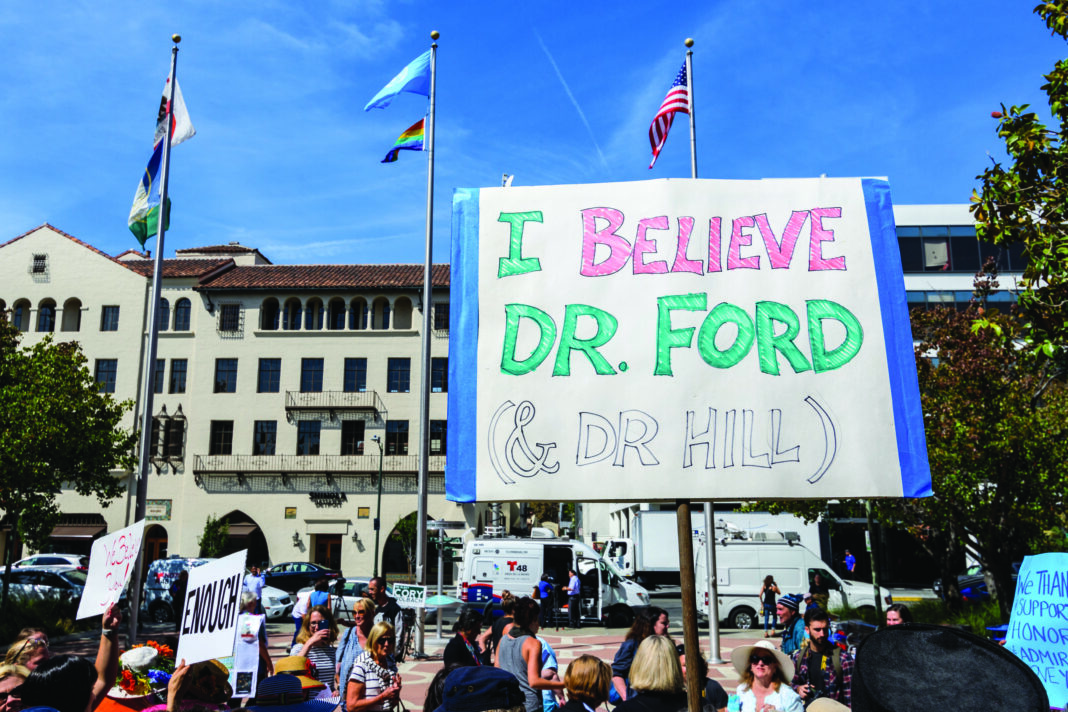

Women very often do not come forward after a rape or attempted sexual assault, or even sexual misconduct, because they know the pattern that will ensue. It’s as much a patriarchal society today as it was when Anita Hill testified in 1991 before an almost all-male group about her treatment at the hands of her former boss, Clarence Thomas.

Anita Hill was attacked, accused of lying and told that her story had no credibility. And that’s exactly what Lindsey Graham, Brett Kavanaugh, Trump and others said about Dr. Ford’s story.

Who would dare come forward in the face of an angry, mocking president who, in a shocking display—even for him—made fun of a woman’s heartfelt testimony about a traumatic experience; a woman who feared she would be raped or killed. Women (and male victims, too) learn to stay in line, to keep their pain and anguish quiet. They learn to internalize the terror and the shame and the bewilderment. No more.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein noted that in 1991, Republicans belittled Professor Hill’s experience and said her testimony wouldn’t make a bit of difference in the outcome. They were right. And now history is repeating itself: “I’ll listen to the lady, but we’re going to bring this to a close,” Graham said.

Senators who wanted to make Ford look like a tool of the Democratic Party probed her about where the money came from to pay her lawyer. But did they think for a second about where the money comes from to pay the therapists, the social workers, the pharmaceutical companies and anyone else who has helped her get through each day?

A recent reporter’s group discussion on Kavanaugh in The New York Times featured a few reporters talking about the hearings and what, if anything, was the disqualifying aspect of his testimony. One reporter said that “people could overlook excessive drinking, maybe some crass comments,” but then things changed. When the hearings ended, the focus shifted to “the truth”—not his college behavior. Said another reporter: “[W]hat bothers people is the degree to which [Kavanaugh] is not representing himself accurately, not the behavior itself. When this all started, the question was, ‘Did Brett Kavanaugh commit the alleged act of sexual assault?’ Now the question is ‘Did Kavanaugh knowingly mislead and deceive’” the public and the Senate? The original allegations were characterized, in comparison to the lies, as “smaller matters.”

I value truth-telling, particularly under oath, and particularly in our Supreme Court judges, but it’s outrageous that accusations of sexual assault, of laughing boisterously as one attempts to rape a young woman, of putting a hand over her mouth to silence her screams, gets portrayed as a “smaller matter.”

It’s no small matter—and especially now that Kavanaugh is on the court.

The second time I was raped in college, by another frat-boy elite, I kept quiet again. I kept quiet despite the bruising on my arms that went from my elbows to my shoulders. I kept quiet despite all the small bruises around my pelvic area where my drunken perpetrator had been sloppily attempting to hit his target.

I did not say anything because I knew if I were to speak up, I would be raked over the coals. Interrogated. Ridiculed. Called a “slut,” a “whore,” a “bitch”—much like Renate Schroeder, the girl Kavanaugh and his friends mocked in their Georgetown Prep yearbooks.

I kept silent, and three weeks later, another girl was raped by this same person.

She talked. She went to the authorities and was demonized, attacked, called a “slut” and a “whore” and a “bitch. Traumatized all over again for heroically coming forward, she left college.

Her perpetrator remained.

Just read the article. Thank you, Tom, for your wonderful edits, and for printing my story. You are to be commended for keeping the story going, not letting Christine Blasey-Ford’s testimony get silenced, as more and more of Trump’s acts of cowardice, cruelty, and utter disregard for human decency continue to pile up!

What an important story. Maia, you are very brave. You were so young when these things happened to you. We were all so naive back then, and there wasn’t all the information that we have now. It’s almost as if you were equivalent of today, what would be 11 or 12 years old. Thanks for being a Hera (hero) and telling this story.