by David Templeton

Je Suis Charlie.

Translation from the French: “ I am Charlie.”

A month ago, that weird little phrase didn’t even exist in any language. Unless, of course, your name was Charlie. And you lived in France. Today, the three-word motto is on the lips of stunned, outraged and heartbroken news-watchers all over the world.

On Jan. 7, after armed Islam-professing terrorists in Paris carried out a violent attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo (“Charlie Weekly”), that simple phrase, a call of universal solidarity against extremism and terror, quickly became a household saying around the world, from the streets of Paris to the stage of the Golden Globe Awards.

The religiously fueled revenge, following provocative cartoons of the prophet Mohammed, resulted in the slaying of 12 people on and around the Charlie Hebdo headquarters. The dead include Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Stephane “Charb” Charbonnier, 47, who was also the publication’s editor-in-chief, along with four other cartoonists—Bernard Verlhac, 57; Philippe Honorè, 74; Jean Cabut, 76; and Georges Wolinski, 80. Also killed, execution style, were editorial staffers and columnists Bernard Maris, 68, Mustapha Ourrad, 60; Elsa Cayat, 54, along with 42-year-old maintenance worker Frèdèric Boisseau, and 69-year-old visitor Michel Renaud, the founder of a popular French art festival, who was attending an editorial meeting at the time of the assault. Two police and security officers—Ahmed Merabet, 40, and Franck Brinsolaro, 49, were also murdered.

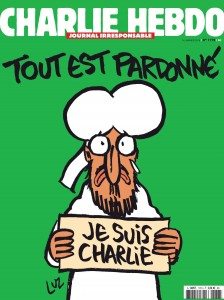

The slaughter sparked marches in France, supporters united in their support of free speech. On Wednesday, Jan. 15, the remaining staffers of Charlie Hebdo, with unprecedented international support from other publications, published a new online version of the magazine, with a cover depicting a cartoon Mohammed, a tear running down his face, proclaiming, “Je Suis Charlie!”

The next day, violent anti-Charlie protests in Niger and Pakistan claimed the lives of at least four more people, and sparked the bombing and burning of several buildings, including the French cultural center and several Christian churches.

“It’s just proof positive of the awesome power of satire,” observes singer-songwriter Roy Zimmerman (www.royzimmerman.com), of Fairfax. “It’s so interesting that it was cartoons that set these people off. Cartoons are immediate. You can look at a cartoon and ‘get it,’ instantly. Though cartoons are just funny little bite-sized messages—with artwork that sometimes barely qualifies as art—cartoons really do have so much power.”

Zimmerman’s own satirical barbs take the form of comedic songs, frequently carrying overt political messages, taking on everything from the American Religious Right to corporate frackers and industrial polluters. Zimmerman has definitely experienced his own share of opposition. One of his songs, Creation Science 101, skewers the anti-science arrogance of Biblical literalists, and the huge public response to the tune on YouTube definitely includes a share of hate-mail attacks from fundamentalist believers. But Zimmerman thinks that the kind of extreme-Islamic terrorism acted out in Paris has less to do with religion than with a thirst for waging really big, publicly-staged fights.

“Religious extremists—which is to say ‘organized crime’—they all thrive on opposition,” Zimmerman says. “They don’t mind being opposed themselves, or disagreed with, or fought against, even, because all of that is a self-defining feature of who they are. They want to be opposed. They invite it. They thrive on it. But what they can’t stand is being laughed at. They hate that.

“If a tiny publication like Charlie Hebdo can have that kind of impact,” Zimmerman goes on, “it’s because one group of people [is] laughing at the ridiculous aspects of another group-—that’s a very powerful thing.”

Zimmerman believes that it’s important for people to separate the religious motivations of terrorists from their acts, which are almost always the antithesis of what their religion stands for.

“We are not dealing with people making a religious point in a logical way,” Zimmerman says. “We are dealing with deranged people—people who are not beholden to any God that any rational person would worship. These are people for whom killing and death represents success. There’s no way to take them on, rationally, so the worst thing we can do to them is to just stand back and laugh at them.”

So while some might suggest that Charlie Hebdo brought this recent violence on by flagrantly provoking Islamic fundamentalists with cartoons depicting the prophet Mohammed as gay, Mohammed as a gibbering idiot, or Mohammed as a human being stunned at the actions of people killing others in his name, Zimmerman points out that the Paris gunmen were, by definition, not religious spokesmen.

“They were criminals, not activists,” he says. “They are murderous thugs. They are a crime syndicate. And like all crime syndicates, they’re only interested in profit.

“They just spell it differently,” he adds.

“That was a joke, by the way.”

Marin County comedian Geoff Bolt has a similar perspective.

But Bolt (www.geoffbolt.com) suggests that it’s not just extremists we have to worry about. It’s our own tendency to want to create enemies.

“We are all indoctrinated to define ourselves by whoever it is we are the opposite of,” he says. “We have a need for enemies in order to define who we are as individuals, or as a nation, or as a school. ‘Kill the Trojans!’ It’s something we are carefully taught to believe. We have to accept that we are indoctrinated, in high school or earlier. We live in an enemy culture. We learn that the football teams from other schools deserve to be destroyed, bombed, killed, obliterated.”

And we even sing funny little songs about it at halftime.

“Our leaders tell us who we are by telling us who our enemies are,” Bolt believes. “When I think of these kinds of Islamic terrorists, the group they remind me of the most is the KKK. The Clan, at least at the beginning, was not a bunch of scholars. They were a bunch of poor white guys, floating somewhere between where really poor black people were, and where the middle class whites were—so they needed an enemy to blame for their poverty and hardship, and they picked the black people and the Jewish people.

“The parallel is significant, I think,” Bolt says. “I don’t buy this kind of thing, this kind of violence, as having a real religious motivation. I think they’re just angry poor people.”

Bolt points out that, even though he’s never been known as a very political comedian, he still feels strongly about this issue.

“I think if we don’t learn from the past, we are going to repeat it,” he says. “Which might explain why my act is always the way it is. I don’t talk about the truth. I just make up stuff about myself, which some people call ‘story telling.’ In my act, there’s always a happy ending. Not in a massage parlor way. More of a Disney way.”

Bolt has, in fact, only ever made one joke that might be regarded at political, in terms of the actions of Islamic terrorists.

Here it is.

“Terrorists believe that when they die and go to heaven, they’ll be immediately rewarded with 70 virgins, right?” asks Bolt. “So … what do you do on the second day?”

Of course, the events in Paris strike especially close to the mark for political cartoonists and the folks who support, promote and defend them.

“I just felt a huge sense of shock, when I heard about Charlie Hebdo,” says Summerlea Kashar, executive director of the Cartoon Art Museum (www.cartoonart.com) in San Francisco. “It was really hard for us here to wrap our heads around how something like this could occur. We had heard about artists being harassed and targeted with violence, but nothing on that scale. The idea that this kind of retaliation could come in response to a drawing, it’s just stunning.

“We were giving a political cartoon show back in 2006,” she goes on, “when the [Danish] cartoonists were being threatened for their depiction of Mohammed with a bomb in his turban, and we thought that was such a major thing. But what happened in Paris makes it look like such a small incident. It’s really hard to come to terms with this.”

While some might assume that the Charlie Hebdo incident will make cartoonists consider lessening the intensity of their satire, Kashar suspects it will do the opposite.

“I think this will cause more people to want to express themselves,” she says. “People whose job it is to share their opinions will probably feel like they have more reason than ever to assure that nobody will tell them what they can and cannot do. There is always some kind of censorship happening, in some ways, but there have been so many people stepping forward to say, ‘I don’t necessarily agree with the cartoonist’s message, but I agree with their right to do it.’ There are a lot of people who believe in that principle.”

The attacks in Paris, of course, came right on the heels of another head-scratching act of censorship-fueled terrorism—the Sony Films hack-attack.

Though the specific perpetrators are unknown, there is evidence to suggest that the government of North Korea hacked the computers of Sony Pictures, releasing embarrassing emails and threatening—in hilariously scrambled English—to commit acts of 9-11-style violence against movie theaters screening the Seth Rogen comedy The Interview. In the comedy, also featuring James Franco, two idiotic television journalists are hired by the CIA to assassinate North Korea’s famously infantile and clearly tyrannical president Kim Jong-un. But first they make him look like a buffoon, which evidently inspired the North Koreans to publically embarrass Sony executives—releasing hilarious internal emails—after which the hackers threatened to carry out acts of terror on movie theaters if the film were ever released.

Sony, pointing to several major theater chains that declined to screen the film, pulled it from distribution, then changed their mind. Immediately following a mysterious Internet failure across North Korea—which some believe was the U.S. government’s own clandestine response to the Sony hack—the studio decided to go ahead and let small art houses and “specialty theaters” screen The Interview. To date, no terrorist events have taken place at theaters screening the film, though many pundits have pointed out that the film is so lacking in true wit, that the whole hack-attack did Sony a favor by making people actually want to see and talk about a B-grade film that was otherwise fairly forgettable.

And then, just as one outrageous attempt at censorship was fading away from the news, Charlie Hebdo happened. The perpetrators, quickly identified through video footage at the scene, were eventually killed in a hostage-taking melee that left more innocent people dead.

“It’s so tragic, and so sad,” says Reed Martin, of the Reduced Shakespeare Company (RSC). “It’s just shocking. It just shows how powerful comedy can be.”

Martin has also seen his share of offended people over the years. The RSC frequently works satirical political or religious material into its many broadly comedic shows, which include The Bible: The Complete Word of God (Abridged) and the recent The Complete History of Comedy (Abridged).

Like many others, Martin—who lives in the town of Sonoma—had never heard of Charlie Hebdo when news broke about the massacre.

“I find it hard to put into words what I feel about it,” he acknowledges. “It demonstrates how satire gets through to people in ways that traditional prose and journalism don’t always do. Comedy is a lot more effective at changing people’s minds than a direct approach usually is. With comedy, with satire, with ridicule, you disarm people. You expose the ridiculous sides of an issue, and that’s just hard to defend against—which is probably why some people go to such extremes when they are the ones being ridiculed.”

Thankfully, Reed and the RSC have never drawn the ire of whole governments or bands of murderous thugs. They’ve never even suffered seriously from attempts to censor their material. The worst thing the troupe has experienced, in terms of attempts to shut them down, is what happened last year in Newtonabbey, in Ireland, when a performance of The Bible: The Complete Word of God (Abridged) was banned at the last minute, by the local city council, on the grounds that it was blasphemous, that it mocked the scriptures, and that it was sacrilegious and offensive to Christians.

To the town council’s surprise, and that of the spiritually incensed councillor Billy Ball, the ban sparked an international outcry, drawing the involvement of Amnesty International, the Northern Ireland Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure—and even renowned atheist author Richard Dawkins. The UK press made a huge fuss about the cancellation, which backfired spectacularly on the council, and the entire country.

“Surely God must have a sense of humor—how else could he put up with the numpties of Northern Ireland?” wrote the Belfast Telegraph in a newspaper piece, with the headline, “Bible spoof ban makes Northern Ireland a laughing stock.” A “numpty,” by the way, is defined by urbandictionary.com as “a stupid or ineffectual person.”

Eventually, the council rescinded its ban, and the show—which previously had sold less than half of its available tickets—played to sold-out houses and lines around the block.

“No one died, thank whatever-Deity-it-is-you-believe-in,” Reed says with a laugh, “and we ended up selling out all three shows. Isn’t that what usually happens when someone tries to shut down freedom of speech? Remember what happened with Martin Scorcese’s The Last Temptation of Christ? Christian groups staged all these public protests, and suddenly, there were lines around the block with people dying to see this movie about Jesus. People make a big stink about something that people wouldn’t normally have paid attention to—and they almost always end up shooting themselves in the foot because suddenly, everyone wants to see whatever it is they’re protesting.”

“I’m just amazed that France has a satirical magazine and we don’t,” observes political satirist Will Durst (www.willdurst.com). “We used to have Spy magazine and National Lampoon, but they’ve been gone for years. The best revenge would be if in response to this, more satirical newspapers and magazines and websites started publishing this kind of material. I’d definitely read that. I might even write some of it myself!”

In addition to Durst’s politically attuned comedy act, he writes a syndicated satire column that appears in newspapers across the country. Durst says that while the syndicate has never censored anything he submits, it’s through angry letters from readers that he knows his column is even being read.

“I never know which papers have picked up a particular column from week to week, until I suddenly get an angry email from Osceola, Florida or Prescott, Arizona,” he says, adding, “They hate me in Prescott, Arizona, but the syndication service has never told me what I can and can’t write.”

For his part, Durst says he’s growing weary of people being offended at everything.

“How come people are always offended because someone doesn’t think like they do?” he asks. “I don’t get it! I don’t get the audacity of people, whether it’s religious people or political people or whatever. It’s OK with them if I’m offended by their practices, but God forbid I should make a joke about them. I’m just kind of tired of it.

“Kim Jong-un’s offended. The Muslims in France and Pakistan are offended. The Christians are offended. Everyone’s offended at something. There was a time when someone would be offended, and they’d deal with it. They’d write a letter to the editor. But they wouldn’t send in the death squads.”

As for comedians and cartoonists and satirists, Durst points out, it’s their job to be offensive, and that should not be forgotten.

“We’re the canaries in the coal mine,” he says. “We speak what other people only feel, and that drags the issues out into the sunshine where everyone can look at them—and maybe laugh a little.”

Interestingly enough, Durst predicts that, while some comics and cartoonists may amp up their incendiary material as a reaction against all of these recent attempts at censorship, the place we will likely see the most demining satire will be on the theatrical stage.

“I think where the ‘Front Line of Political Satire’ will grow the hottest is in the work of our playwright,” he says. “It’s already happening. Theater is a powerful medium for free expression, because it’s people expressing themselves through the power of human stories, and when there’s humor worked into it, even the most brutal satire can reach right in and shake you! So maybe the stage is where we’ll see the satirical voices grow stronger.”

Asked what advice he’d give to writers, artists and comedians pondering how to proceed in the aftermath of recent events, Durst is to the point.

“Just be honest,” he says. “We should all stay authentic. We should say what we feel about this, down in our guts. Just say it! And then try to make it funny.”

Funny? People are dead, and more deaths may come in the wake of ongoing protests. Can such tragedy actually be made funny?

“Yes,” Durst says. “Of course it can. Nothing is so awful we can’t find a way to understand it better through humor. No matter what, there’s always a way.”

Humor David at ta*****@*******nk.net.