By Tom Gogola

Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairymen in Sacramento, published an eyebrow-raising memo on August 26 in response to the debate underway in the California State Legislature over a contentious effort to overhaul the state’s overtime rules for farmworkers.

Raudabaugh, whose organization lobbies on behalf of state dairy farmers, was responding to implicit charges that opponents of proposed overtime extensions to farmworkers had played the proverbial race card, and the lobbyist flat-out went off on legislators who had thrown the card into the debate. “The snowflake culture, a culture that some belong to and feel entitlement is owed and due,” she wrote on the Dairymen’s online newsletter, “is one that utilizes the cry-bully tactic and calls its enemies racists, slavers, and falsely sows the seeds of hatred to damage the logical optics in play on an issue.”

The correct view in this case, she added, is a focus on choice—as in, the choice of workers to labor in the fields, which was theirs to make. The “logical optic with the allowance of agricultural overtime—along with many other industries and sectors that have been given the exemption to overtime, is that this is a VOLUNTARY method for people in this state to make money and decide for themselves how to feed their families. Eliciting phony racism sentiments and likening agriculture to slavery is the lowest point the conversation could have gone. I don’t think the leadership’s capacity for loathing agriculture could be matched with this low blow.”

Raudabaugh’s note did not mention that, as harsh as it may sound, dairy farmers themselves are not obligated to participate in their chosen industry, but let’s set that aside for the moment. The bill, AB 1066, was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown in Sacramento on Monday, September 12. It was passed through the Legislature with healthy majorities, and will phase in new overtime rules over the next nine years. The bill was also passed without the support of most of the North Bay delegation to Sacramento, a curious development given that they’re all Democrats and this is a very ag-oriented region where there is general consensus that farmworkers are a struggling class of workers whose efforts are critical to the economic well-being of the region.

But there you have it. Senators Mike McGuire and Jim Wood joined assemblymen Bill Dodd and Marc Levine to either vote against the bill or abstain from voting. Napa senator Lois Wolk was alone among North Bay legislators to vote aye for time-and-a-half hourly overtime wages at the heart of the bill, which was sponsored by San Diego Democrat Lorena Gonzalez and offers a phased-in overtime regime for agriculture workers, beginning in 2019. Farms with operations of fewer than 25 workers will be phased in beginning in 2022.

In voting no, the former Republican Dodd emailed in advance of the Labor Day holiday to say that, “I had concerns with the bill that weren’t worked out, so I wasn’t able to support it. I’m supportive of what it’s trying to do, but I want to ensure that changes are balanced and crafted in a way that minimizes unintended negative consequences.”

There lies the rub behind legislators’ no votes and abstentions from the final vote, whose rationales tended toward an implied critique of its one-size-fits-all approach to agricultural workers that lumped dairy and cattle workers in with fieldworkers. Dodd’s district is exceedingly agricultural in its fidelity to Big Grape, but you’d be hard-pressed to find a dairy farm in Napa County.

McGuire offered a more specifically anguished reasoning behind his did-not-vote posture on the bill. He’s got dairy and grape farms in his district, which includes all of Marin and most of Sonoma County.

“This was a difficult decision,” McGuire says via email. “I’m never going to vote against farmworkers, which is why I stayed off the bill. The concerns we advanced relating to small family farmers and dairy owners here on the North Coast were never addressed. Given the tight time frame of this bill we were unable to find middle ground.” Lawmakers signed off on the overtime measure in the last-minute legislative scramble before the Labor Day break, when bills had to be moved or scrapped.

Dairy owners are already paying more than twice the average wage than fieldworkers, according to advocates I talked to who represent those respective workers. Factor in a state dairy industry that is already highly subsidized—which could collapse without annual federal subsidies to prop it up and where the price of milk is essentially socialized with state-set price controls—and the no votes begin to make a little more sense, despite the clear and obvious social-justice question at the heart of the farmworker wage battle.

Because of the price controls and rules governing the subsidies, dairy farmers can’t pass off increased labor costs to consumers if they are forced to pay higher wages. Non-dairy farmers were also opposed to the new overtime bill and argued that it would force them to further automate their operations to make up for the workers they’d no longer be able to afford to hire or pay.

But let’s back up a minute here. To understand the genesis of Raudabaugh’s juicy online riposte—whose “snowflake culture” language is more typically seen in rightward-leaning discourses that slam college campuses over trigger warnings and safe spaces as a bulwark against the dreaded onslaught of the oversensitized and politically correct—the overtime bill aims to move California beyond federal overtime rules that date back to the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt and are enshrined in The Federal Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which, as AB 1066 itself recalls, “excluded agricultural workers from wage protections and overtime compensation requirements.”

California, as Raudabaugh observes, is one of four states where overtime pay does kick in for all farmworkers, at a 60-hours-worked threshold. The bill that Brown signed offers overtime pay through a phase-in period and by the time it’s fully implemented, overtime would kick in at 40 hours worked, for all workers, in 2025.

Marty Bennett of North Bay Jobs with Justice, which vociferously and unsurprisingly supported the overtime overhaul, says that the bill is “at least a half a century overdue and it really does go back to the era of segregation, when African-Americans were cut out of wage-hour legislation because of Southern segregationists in Congress. Roosevelt cut a deal with the racists,” who at the time were Southern Democrats hell-bent on enforcing Jim Crow, often through lynching and other terror tactics. It was an ugly compromise for its dust-bowl time, but what does that have to do with Northern California Democrats in 2016?

Well, sure, there’s a drought. And AB 1066 was passed amid an unpleasantly anxious backdrop as California’s agriculture industry faced almost $9 billion in losses in 2015, according to an annual state crop report issued last week by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that garnered headlines around California. The biggest drop was in the dairy industry, which accounted for about one-third of the total lost revenues between 2014 and 2015, and which saw state output plummet from $56.5 billion to $47 billion. The trickle-down impacts have been just shy of disastrous for the dairy industry, as hundreds of dairy operations have been driven out of business around the state since the advent of the drought.

The drought extends to North Bay fieldworkers themselves, who are very definitely feeling the pinch of low wages and could use a rainmaker of their own to come to the rescue. An October 2015 report from the Sonoma County Department of Health Services focused on farmworkers’ health and well-being, and is filled with awful stats that tell the story of a woefully underpaid workforce that binge-drinks too much and can’t afford the rent as it noted that 92 percent of farmworker families didn’t “earn enough to meet their family’s basic needs in Sonoma County.” The survey highlighted a “dramatic disparity between farmworkers and even the poorest Sonoma County residents.”

And the USDA report found confluence in Sonoma County, where the 2015 crop report found a “dramatic decrease in yield” between 2014 and 2015 which translated into a 14 percent decrease in total crop value over those two years—$756 million from $879 million in 2014.

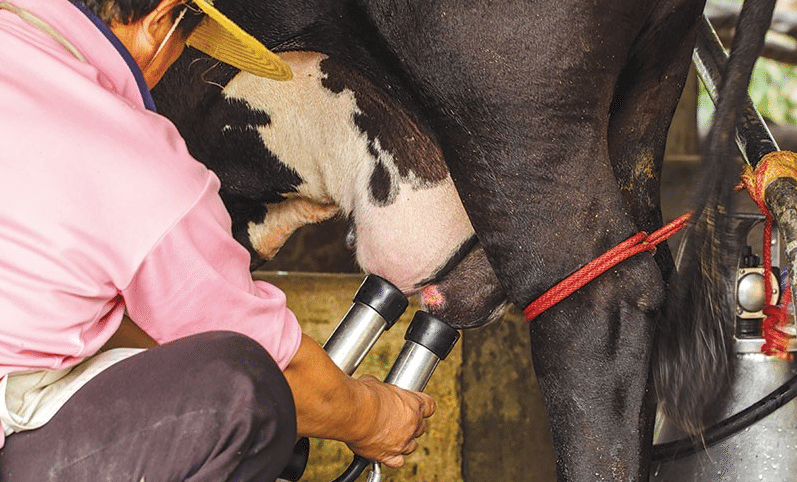

As the overtime battle unfolded, critics noted that the United Farm Workers, which represents California laborers, could have fought for overtime benefits for their workers through collective bargaining instead of pushing through the Legislature a wholesale redo of the entire agriculture-worker economy, where fieldworkers earn an average of $9 an hour, says Bennett, though dairy workers are in the $21-an-hour range, according to Raudabaugh. A collective-bargaining set-to was always going to be a losing fight, say observers of the process, and supportive lawmakers led by Gonzalez took up the call this year to force the issue across the board, from grape field to milking station.

There’s a big difference between picking grapes and milking or slaughtering cattle, and Raudabaugh says that higher wages are paid to cattle-workers because of regulations and sanitary requirements and the cattle themselves, who must be managed in a responsible and humane way. Because of the skill set and particularities of the industry, she says “we want to hire the most competitive labor possible.”

The particulars of the dairy industry are also distinct from other agricultural pursuits when it comes to those subsidies and price controls. According to federal data compiled by the Washington, D.C.–based Environmental Working Group, between 1995 and 2014, the Sonoma County dairy industry received $17 million in federal subsidies out of a total of $95 million that flowed to the county, the highest subsidy delivered to any sector of the economy, including emergency services.

Marin County, which hosts numerous small- and mid-size dairy operations that provide some of the country’s most sought-after and delicious dairy and cheese products, not to mention the beef itself, got $6 million in subsidies over that same time, out of a total of $13 million.

Clover Stornetta works closely with 28 family farms in Sonoma and Marin counties to make its organic milk products in Petaluma, says company CEO Marcus Benedetti, who adds that “the impacts are on their cost side” as he highlights the price controls that restrict any North Bay dairy operation’s ability to cover increased labor costs with a higher price at the market. And he notes the particulars of the local dairy economy itself, where workers at some dairies that contract with Clover Stornetta are housed on-site—a form of compensation in the high-rent North Bay. “In many cases, it’s a community,” Benedetti says of local dairy operations, adding that “not all dairy is monolithic in the state of California, and these farms here are vastly different than what you’ll find in the Central Valley,” with its corporate and decidedly non-organic mega-dairies.

In a recent interview, the Dairymen’s Raudabaugh reflected on her blistering critique of the Sacramento snowflake crowd with a chuckle as she defended the pushback against social-justice arguments for the bill that focuses on race. “I do think the race card was played here, and once that rabbit hole was gone down, it became a very difficult argument to overcome logically,” she says.

Raudabaugh, who has been in her post since 2015 and was once a staffer for former Republican Congressman Doug Ose, stresses that she is “respectful of the dynamics; this is a social-justice issue and I am cognizant of that.”

But she says the race card tainted what should have been a rugged and logic-driven debate over the catch-all nature of a bill that did not distinguish between respective groups of farmworkers and failed to appreciate the struggling margins that dairy farmers, many of them minorities, already occupy.

“It’s really deployed when you have no merits left in the argument,” Raudabaugh says, noting that “we have a very Latino- and black-owner industry, my owners are across the board, but that is not how it was depicted.”

The final bill, with its phase-in of the overtime changes, appears on its surface to be a compromise bill that reflected input from concerned parties such as the Dairymen. Raudabaugh says the lobby has expressed its misgivings to Brown and worked to create a better bill for its members despite ultimately opposing it. And despite the phase-in period designed to lessen the blow on farmers’ bottom lines, she says dairy workers are already fretting. “The scramble is already on to see how to make this work without having to let people go.”

Why weren’t there two separate tracks or a bill that excluded dairy and cattle farms from its scope? “Believe me,” she says, “the Dairymen talked about it but there was no separate effort” by any legislators to offer a bill that would be “better tailored to the types of commodities that we are looking at. There is an intense harvest period for cabbage, for grapes,” she adds. Dairy work is not seasonal or subject to high-season hiring spikes and “some of the more logical lawmakers who did not know that were put into a corner, and there was no way for them to win that corner,” she says. The fix was in when lawmakers started making speeches about how their relatives were sharecroppers, she says, while stressing that she’s not unsympathetic to the history.

“I don’t discount those things,” she says, even if many lawmakers did not appreciate the particularities of the dairy and cattle industries as they made speeches over past racial sins and tied them to the current battle.

Marc Levine was among the lawmakers whose position synced with the dairy industry. The lawmaker’s district, which straddles Marin and Sonoma counties, produces many millions of dollars a year in specialty organic cheeses and dairy products, and Raudabaugh says her office discussed the bill with the two-term Democratic assemblyman “at great length.” Levine didn’t vote for the bill, and Raudabaugh notes that his district is filled with the putatively progressive new-economy farmers, “the smaller producers, the non-GMO, the grassfed-beef ones—those are the ones that are going to take this the hardest.”

In a telephone interview, Levine says it was a difficult call to abstain but insists it was the right call. The lawmaker notes that he has supported other efforts designed to address income inequality and that he spoke to Gonzalez about the unintended consequence her bill would bring to family dairies. The major unintended consequence he fears is that farm owners will put “downward pressure on the number of hours on the schedule” and reduce work hours for all their workers and tear at the “amazing but fragile dairy economy” of the North Bay.

Levine says he is all for raising the wages of the lowest paid and lowest skilled farmworkers but sees a value in pushing on other fronts to get at the strain on the weekly paycheck and the person signing the check—affordable housing being the standout concern in the North Bay, not to mention the boutique nature of much of the dairy action here. “It’s challenging to distinguish between multibillion-dollar ag enterprises and dairy farms that young entrepreneurs are trying to start with a commitment to the local ethic,” he says. “I want to treat all workers fairly,” he adds and highlights, for example, efforts that small-time operators put into providing on-site housing for their workers.

But legislators’ efforts to cleave cattle from the overtime bill did not ultimately hold sway. Once the specter of race was raised, Levine says “it became a difficult conversation, and unfortunately the national political conversation today is quite toxic.”

But hey, at least the milk is organic.