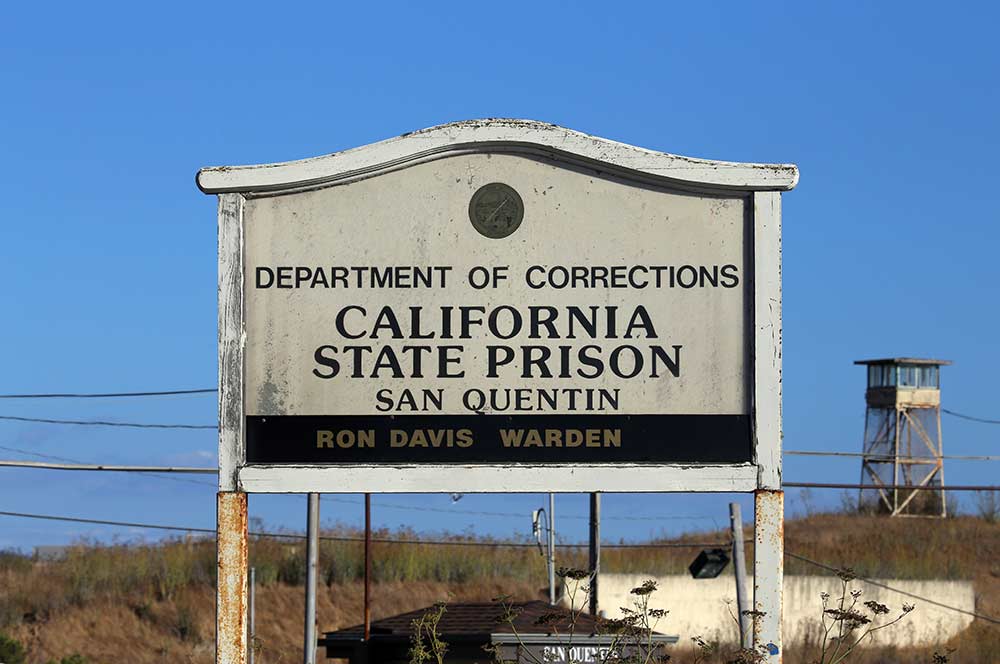

San Quentin State Prison is the only prison in California that executes condemned men, but there hasn’t been an execution there since 2006. However, Death Row still exists, and the heavy vibe that permeates that world is still palpable.

The last exit to San Quentin on Interstate 580 is an easy right turn just before the Richmond Bridge. The person I’m visiting is Jarvis Jay Masters, a most remarkable man who’s been on Death Row for 38 years—21 of which were in solitary confinement—longer than any other prisoner in San Quentin history. I know Jarvis to be an innocent man, wrongfully convicted, and we have been friends for 20-plus years.

A visit to San Quentin is a journey into juxtaposition. The ride along the rocky coast where the prison sits fills one’s eyes with the ocean’s raw beauty and the familiar sounds of the sea against the shore. All this is set against the stark background of drab and aging buildings that house desperate souls with grim prospects.

In the visitor’s admission’s building, children of all ages, mostly black Americans, play and laugh and sometimes get scolded by worried families while awaiting entry. A common-enough scene as compared with the next step—the tightly confined, caged visit with their inmate relative or friend. It’s a contrast of childhood enthusiasm with the heavy reality of the inmate’s locked-down life.

As with entering any new place, it helps to know the customs and rules of the land. Here’s a little primer:

Gaining access to someone on Death Row is by appointment only and requires jumping through many hoops and considerable phone time. It takes hours of busy signals, interminable waits on hold and getting disconnected repeatedly. Hours turn into days, as business hours are limited. Once at the prison, getting inside to see family or friends is a strictly regulated procedure. You’d better know the scene, or you’re in for some misery.

Unsuspecting newcomers to S.Q., as it’s commonly called, await admission in a long, narrow, windowless building, anywhere from one to three hours, only to be told their clothing is wrong. They can’t wear blue, green or brown—those colors are for the guards and inmates. Visitors are then directed to a distant, small building, where they’re issued alternative clothes. No prior warning or notice is given. The message is clear: “We have the power—you have no say in the matter.”

The same message applies to the inmates. They’re issued identical, prison-blue denim pants, shirts and jackets. Message understood: “You have no identity here. You’re just another blue-clad being in the herd.”

Most of the guards I’ve come across are a pretty decent sort, but of course there are jerks, just like everywhere else. Once you get through the outer first station and pass muster with its long list of restrictions and searches for possible contraband, it’s not an unpleasant walk—except in cold, wet weather—up to the second station that houses the visiting sections.

Visits with inmates are either what’s termed “contact visits”—face-to-face in the same metal cage—or “non-contact visits,” which are done by phone, through a thick Plexiglas separator, like in the movies. The sound quality on these phones ranges from very poor to inaudible. Such is the fun of prison visits.

That’s the most I’ve ever seen of the inside of San Quentin, and it’s enough. It was originally built in the 1850s, but I’d say they constructed its current buildings much later. It’s not a dungeon, but it looks and feels maximally institutional and operates on a bureaucratic scaffolding of rules and regulations that cannot, and will not, be broken or bent.

So what?, you might be thinking—prisons aren’t supposed to be playgrounds; we incarcerate people for a reason. And that’s true. But there are also people there, guards and visitors for instance, who’ve committed no crimes, but nevertheless spend time there. Truth is, nobody cares that much about living, breathing people—especially the visitors—but the guards have a union and therefore a voice. Curiously, they, too, spend time in lockup, and that’s what they have in common with their prisoners. Among these inmates are some angry, violent and dangerous people who need to be separated from society. There are also many who don’t fit that bill, but that’s another matter.

Each visitor and inmate share an approximately 4-by-8-foot, heavy steel mesh cage; there are about six cages per row and three rows in total. They’re all joined together, forming one gigantic cage partitioned by steel-mesh walls. There’s no privacy; guards patrol constantly, and conversations from neighboring cages are easily overheard. Me, I’m far too concentrated on conversing with my friend to even hear what’s going on around me, and I couldn’t care less anyway.

A wall of vending machines provides a background soundtrack while inmates await a break from the usual prison fare. It’s a strange mixture of life’s mundanities and sanctioned death.

If the prisoner hasn’t already arrived at the appointed cage, he enters the visiting room via a separate entrance—accompanied by guards, of course—and they open the cage from the opposite end. The inmate, his hands handcuffed behind his back, stands at a narrow opening on that side of the cage, and a guard unlocks the cuffs. Visitor and inmate are then allowed one hug. One more hug is allowed when visiting time is over. Visiting time is three hours max.

I’ve become increasingly claustrophobic over time. Airplanes freak me out and I’ve pretty much given up on flying. I can overcome it in this situation, though, because the cage lets in air, light and sound—and if I concentrate on the conversation at hand, I can pretty much drown out the surroundings and ignore the other cages and their inhabitants. We humans are nothing if not adaptable, otherwise why would anyone put up with steerage-class air travel or commuter traffic, day in and day out? Some of us can even adapt to jail.

But my point is not about what prisons look like or how they operate. My descriptions simply set the scene. This account is about freedom and what that word has come to mean for me.

Prison not only confines the human body to an 8-by-10-foot cell, it also restricts virtually all human activity except for thinking. There is no freedom of choice, as authorities make all decisions for the prisoners: when and what to eat, when to sleep and get up, when to bathe, when to exercise, what to wear, with whom one can communicate, and so on. Even when to die, in some cases. Everything we take for granted in our everyday lives no longer applies inside those drab, cinder-block corridors, where the law regulates and regiments an inmate’s life every hour of every day, week, month and year until they are out, or dead.

That’s life, for the masses, in our prisons.

When a person goes to prison in this country, they abandon every aspect of their freedom. Their life, for all intents and purposes, no longer belongs to them. It belongs to the state and its representatives; the prison officials. They place the choices that govern almost every aspect of a person’s life in the hands of others, and what that person wants or doesn’t want and needs or doesn’t need, is no longer up to them. They have, in a sense, been reduced to zero.

I’m always struck by two things after leaving San Quentin: What it means to be free, and the beauty of the natural environment just beyond the prison walls. They built San Quentin along the coastal bay, almost right alongside the water’s edge—a high, fortress-like tower dominates that point. Across the bay a housing development—probably an upscale one, given its location—is nestled into the coastal hillside. Anything along the San Francisco Bay is high-end property. One assumes any developer would sell their soul to get their hands on the property on which San Quentin sits.

I walk out of the prison and take deep breaths of sea air, cleansing and reviving myself, heaving a sigh of gratitude for the cries of the gulls. I feel the ocean’s cool breeze and invite the chill. I notice my own footsteps and feel my body as it carries me to my car. And then … I can go wherever I want to go. Any direction I choose, to any destination I want. And in that moment I realize what freedom is.

Freedom is not “just another word for nothing left to lose.” Freedom is not a word. It’s not a concept. It’s not a lyric in a song, no matter how good that sounds. Freedom is something real and tangible. Freedom is having choices. Don’t let anyone tell you different.

—- Sidebar —-

Jarvis Jay Masters was wrongfully convicted of the crime of taking part in the plot to murder a prison guard in 1985 and became a victim of both a corrupt legal system and wholly incompetent legal representation. Despite a wrongful conviction and decades of imprisonment he has led a remarkable and highly productive life. Readers can access his full life story at www.freejarvis.org.

Simon & Schuster will publish The Buddhist on Death Row, a biography written by noted author/journalist David Sheff about Master’s life and accomplishments, in 2020. davidsheff.com.

Interesting first-person experience about visiting San Quentin, but I am still waiting to hear about the Meaning of Freedom, we offered in the articles sub-headline. I was really hoping to hear the perspective of Jarvis Jay Masters, the death row inmate with whom the author purports to be friends of two decades. This was a decent first installment, but I am hoping for a second piece that will truly reveal the Meaning of Freedom to the folks on death row at S.Q.

This article reminds me of the Rolling Stone story that also featured a “wrongly convicted” Buddhist prisoner. What a coincidence. It also reads like a high school student’s report on prison. Zero new information. Zero real insight. Yeah, prison sucks. The military sucks as well. You all wear the same uniforms, get told what to do. One is subject to the capricious whims of another contained in a unfair, hierarchical structure. Give me some insight not regurgitate some worn out cliche’s.

Just plain lazy writing. Pacific Sun used to have good writing. Not anymore.