When you buy marijuana on the licit or illicit market, do you know what you’re really getting?

Even if the product has been sold by a dispensary and there’s a label with THC and CBD percentages, the information might be inaccurate. Someone along the line might have concealed the facts.

That’s why the American expression, “Let the buyer beware,” applies to cannabis as well as to all kinds of products, from olive oil to snake oil. When the seller knows more than the buyer about goods and services, it’s known as “information asymmetry.” Sadly, the cannabiz is awash with it.

Part of the problem is that much of the illicit weed on the market isn’t tested. The grower’s and the dealer’s word are all that the buyer has to go on. Also, some testing services fudge results and report higher levels of THC in flower than is actually there.

Not every grower is dishonest and not every testing service is sketchy. Many are transparent. Sometimes, the most truthful fellows are the outlaws, not the law-abiding folks. As Bob Dylan once said, “To live outside the law you must be honest.”

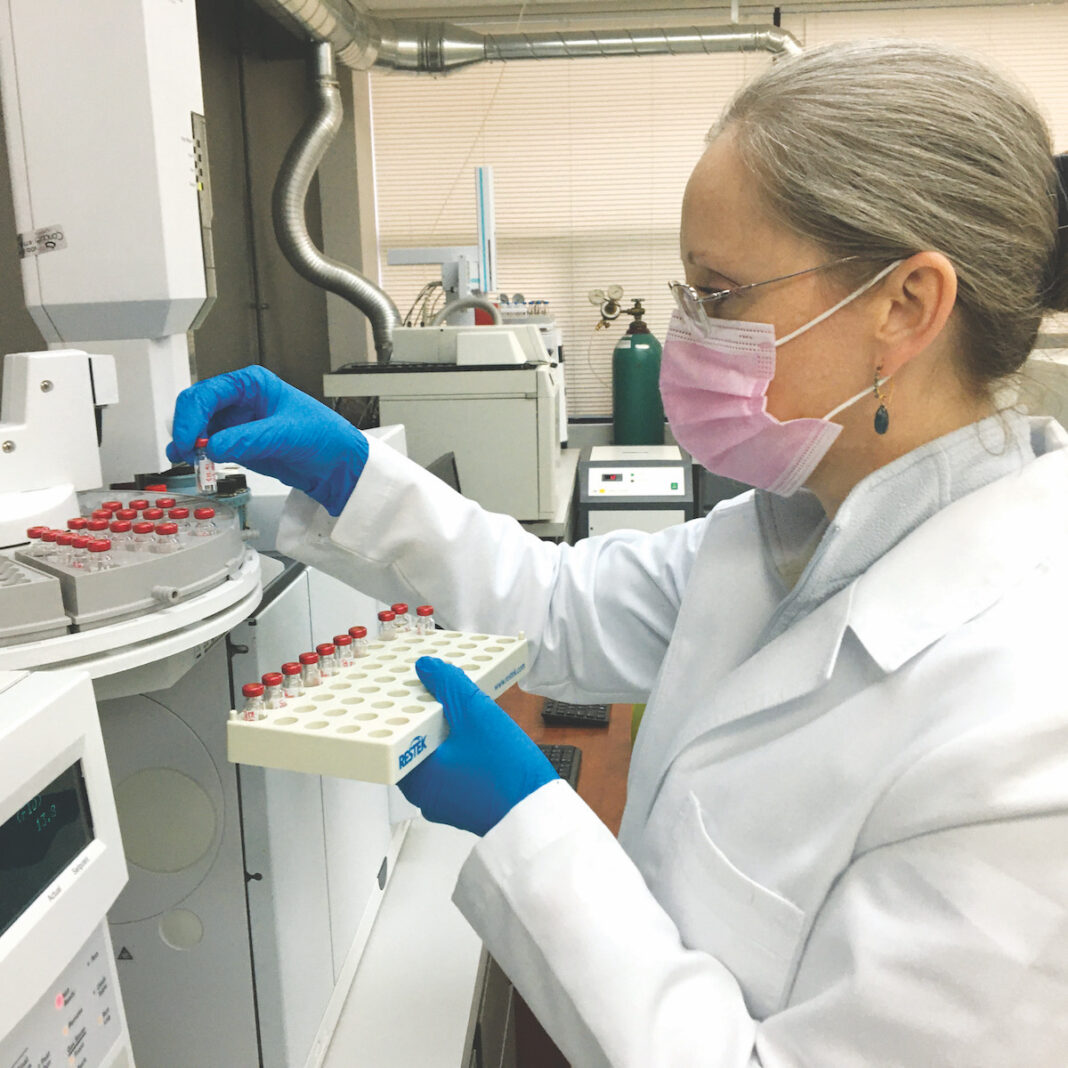

Samantha Miller, a trained scientist who owns and operates Pure Analytics, has tested marijuana from all over California for a decade. She and her team at the Santa Rosa lab adhere to the data and the facts.

“For years, the industry focus has mostly been on potency,” Miller tells me. “But I’ve recently heard that some buyers want unique terpenes.” She adds, “That’s a good sign.”

What’s not a good sign, Miller tells me, is that there’s been a dramatic uptick in the amount of THC (between 35 percent and 40 percent) that labs post online after they test cannabis flowers.

“That didn’t seem plausible,” Miller says. She talked to folks in the cannabiz and found that many of them shrugged their shoulders when she mentioned the uptick. “That’s the market,” was the standard reply.

Miller asked questions, dug deeply and put the pieces together.

Consumers often want THC-rich weed, she explains. Growers get $2,500 a pound for weed with high levels of THC, maybe a thousand dollars less for weed with 20 percent THC.

The third group of players in the mix are the labs that generate the high numbers. The dollar, not science, drives the data.

It’s called “pumping the numbers.”

Miller doesn’t point fingers or call names. But she has sound advice.

“Consumers ought to rely less on numbers and more on their own senses, especially smell,” she says. “Often, the stronger the bouquet, the more effective the product. Pay for what’s real and get the most for your money.”

Jonah Raskin is the author of “Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War.”