by David Templeton

“The problem with faith-based films is they kind of don’t play fair.”

This remark comes not from a film critic, or social activist, or anti-religious pundit, but from a teenage girl with blonde hair, engaged in a conversation about film at the Christopher B. Smith Rafael Film Center.

Last week, I was talking to a bunch of kids as part of the California Film Institute’s (CFI) annual Summerfilm youth program, a presentation of CFI’s ongoing educational efforts.

Each year, I talk to the students—usually between 15 and 30 teens recruited from around Marin County—sharing inside information about being a film writer, and the history of criticism as an art form.

Eventually the kids always ask me to list my favorite or least favorite films, or to explain why I might take issue with some particular genre of film. Last Thursday morning, in answer to that last question, I admitted that I find slasher films—particularly of the Saw and Hostel variety—along with faith-based films like God’s Not Dead and Christian Mingle, are not to my taste, primarily because they are so focused on a narrow audience desperate to see images and messages that move them, that they often settle for a kind of artless mediocrity.

I did list a title or two in each genre that I believed were exceptions to that rule, and as I was finishing, the aforementioned young woman, sitting in the second row, raised her hand to tell me her opinion of God’s Not Dead, a 2013 film in which an atheist college professor (played by outspoken Christian actor Kevin Sorbo, of Hercules fame) challenges his students to prove that God is not, as he insists, dead.

“My problem with the movie,” she says, “is that it cheats. It’s not fair, because it makes all the believers seem wonderful, and the non-believers seem like really bad, awful people. That’s not the way it is in the world. So it makes its case, but it makes it based on a lie.”

Somebody hire this girl, because she’s a film critic waiting to happen.

After the workshop, I got to thinking about this exchange, and started asking myself a few questions. She’s right, that many faith-based films use broadly sketched stereotypes to represent non-believers, but of course, mainstream movies have been turning believers into comic foils and stereotypical villains for as long as there have been movies.

Eventually, I remembered one movie that worked miracles in turning all of these stereotypes back on each other: Robert Zemeckis’ 1997 science fiction brainteaser Contact.

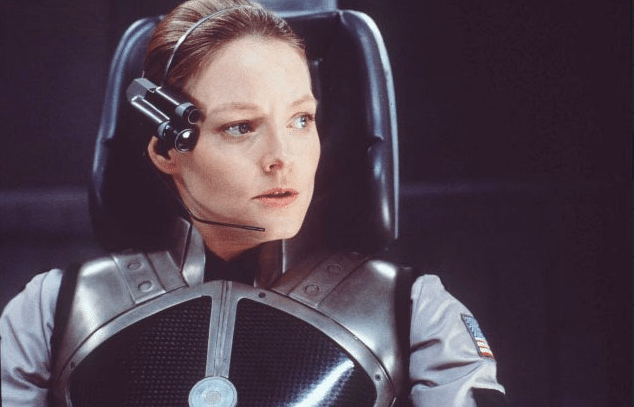

When the film—starring Jodie Foster in one of her best performances—first came out, I took Dr. Eugenie Scott to see it, and now, with these thoughts fresh in my mind, I went and pulled out the recording I made of our conversation.

Scott is a physical anthropologist with a resumé full of distinguished teaching appointments, and at that time was the executive director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), a nonprofit watchdog group headquartered in the East Bay. Since 1981, the NCSE has monitored creation/evolution skirmishes in public schools. Scott, who now serves the NCSE on an advisory level, was a 1991 recipient of the Public Education in Science Award, given out by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal.

She is, by all definitions of the word, a non-believer.

And that label is part of what made me want to revisit the conversation.

“You know what I think?” Scott asked, early in the discussion. “I think we non-believers need to find a term other than ‘spiritual’ to describe many of our profound experiences. I wish we could find a word that means awe and wonder and excitement and love, without the supernatural twist that ‘spiritual’ has.”

We spent a bit of time dissecting Contact, a remarkably powerful drama based on the 1984 novel by the late scientist Carl Sagan. The film concerns a worldwide clash of values and ideas, mainly between science and religion, that occurs after radio signals from space are detected and identified as an invitation from an alien race. Foster plays the scientist who discovers the message, a practical woman and dedicated seeker of answers, whose intense empiricism becomes an issue when she volunteers to be the first emissary to the solar system from which the signals originated.

In one key scene, Foster is asked by an international selection committee if she is a ‘spiritual person,’ by which they mean, does she believe in God? She doesn’t, and, squirming uncomfortably, it is clear that she doesn’t like the ambiguity of the word spiritual.

“It must have been terribly awkward,” Dr. Scott continued in her analysis of the scene. “I can certainly identify with her. How do I talk about something that is non-material yet is also non-supernatural? How do I talk about the awe that descends on me when I go to the top of a mountain? Or when I hear the Queen of the Night’s aria from The Magic Flute, and the hair goes up on the back of my neck?

“I don’t think those feelings are supernatural, but they’re not exactly material either. So I wish I could come up with a term—one that wasn’t clunky—to express that. ‘Non-material non-supernaturalist’ doesn’t exactly fall trippingly from the tongue, now does it?”

In movies like Contact and God’s Not Dead, whenever a character identifies himself or herself as an atheist or a believer in God, you can see the hackles rising on the characters who hold a different view.

Scott, for what it’s worth, suggested during the conversation that she prefers “agnostic” to “atheist,” as she is first and foremost a scientist.

“I would agree with good old Thomas Henry Huxley,” she continued, “who said, ‘The only reasonable attitude for a scientist to take would be agnosticism, because you really cannot know if God exists, so you shouldn’t be an atheist.’

“For a scientist, ‘I don’t know’ is a perfectly acceptable answer,” she added. “You don’t accept the first explanation that comes along. Somebody shows up and says, ‘Aunt Rosie can find water with a forked stick. She’s found it five times in the last 10 years.’

“OK. Is there another explanation? To me the best thing we can do in our society—in terms of teaching people to think—is to get children trained immediately to say, ‘Is there a better explanation?’ And of these explanations, which is the better supported when I go to nature and look for the support?”

I recalled another remark Scott made, but had to skip to the end of the tape to find it. But I did, and my thanks to the young woman in the second row whose remarks sent me in search of it.

“I saw a bumper sticker the other day,” Scott said. “It read, ‘Thank God for Evolution.’ I can appreciate that. I wish we had more people with that kind of sense of humor. It would make my job a whole lot easier.”