By David Templeton

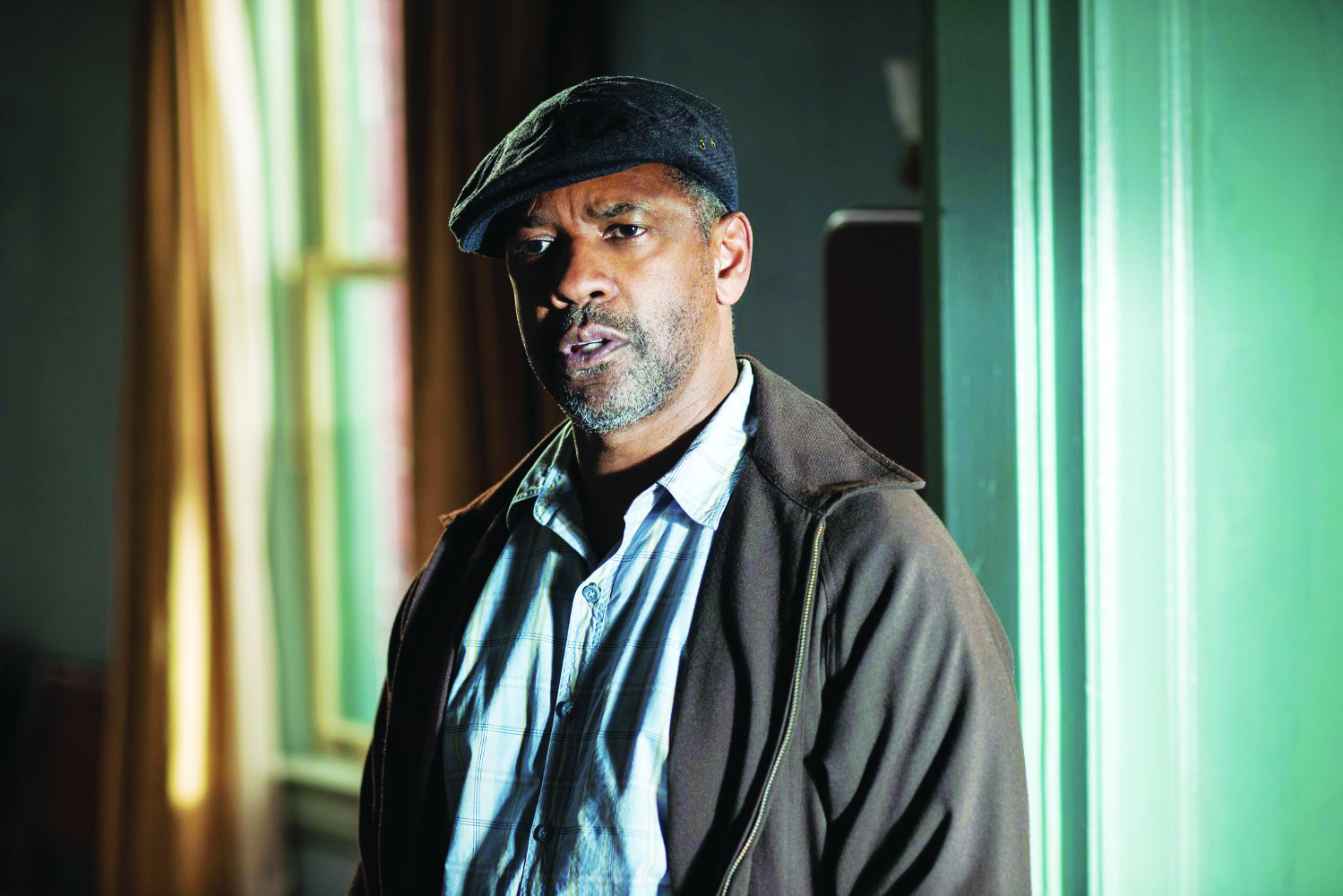

“The 10 stage plays of August Wilson are an American treasure,” actor/director Denzel Washington has repeatedly noted over the last few months. “Now that Fences has finally been put on screen, I plan to see all nine of the others made into films, too. That’s my life’s work, now.”

As “life’s works” go, transferring Wilson’s spectacular cannon from the live theater to the movie theater is one of the best one’s a fan of plays and films could ever imagine. Commonly listed alongside Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee as one of America’s greatest playwrights, Wilson’s own life’s work was the Century Cycle, 10 plays about the African-American experience, each one set in a different decade of the 20th century. Wilson finished the last two plays in the cycle—Gem of the Ocean, set in 1904, and Radio Golf, set in 1997—in the final years of his life.

Smack in the middle of the cycle, set in 1957, is Fences, the first of two August Wilson plays to win the Pulitzer Prize. The other was The Piano Lesson, set in 1936.

Washington’s screen adaptation of Fences, it turns out, is the first of the 10 to successfully make it to the big screen, in part because of Wilson’s demand that only an African-American director be allowed to helm the project. The critically acclaimed film has now been nominated for a 2017 Best Picture Oscar, along with nominations for Best Actor (Washington), Best Supporting Actress (Viola Davis) and Best Adapted Screenplay, which was written by August Wilson himself, several years before he died in 2005.

With the Oscars taking place this weekend, Washington is the odds-on favorite to win Best Actor, and though Damien Chazelle is expected to win Best Director for La La Land, some are predicting an upset victory of Washington in that category, too.

Either way, the success of Fences is an excellent kick-off to the plan of turning all of those other plays into movies. Washington insists that he will not appear in or direct all of them, but has recently inked a deal with HBO Films to executive produce the rest of the cycle. So he will most definitely be overseeing the epic project. No announcement has been made about which of Wilson’s plays will be the next to get the big-screen treatment, but given that Washington has started in the middle, it’s unlikely that he plans to bring them out in chronological order.

Another factor that Washington has yet to remark on is that not all of the plays appear to lend themselves to a cinematic treatment. In fact, the one recurring criticism of Fences, the movie, is that its “play nature” never gives way to the more opened-up demands of cinema. Wilson did not include a lot of scene changes in his plays, and every one of them is set in a single place—a living room, a backyard, a recording studio, a restaurant, a taxi station, etc.

“Wilson’s plays aren’t always that easy to stage … on the stage,” noted Jasson Minadakis, artistic director of Marin Theatre Company (MTC), following his company’s stellar stage production of Gem of the Ocean in January of 2016. That production was directed by Daniel Alexander Jones, and has been nominated for several awards by the San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Critics Circle, with the awards being given out on March 27.

Asked last year when Marin Theatre Company would be staging its next August Wilson play—having staged Fences in 2014 and Seven Guitars in 2011—Minadakis said, “Soon, very soon,” adding that producing a Wilson play is not something one does unless all of the right people are in place. Thus his remark about August Wilson’s plays not always being easy to present in their original stage form. So bringing all of the Century Cycle to the screen is certainly going to be a challenge, regardless of which order Washington ultimately chooses to make and release them in.

My hope for the next one to hit the screen? Gem of the Ocean. Not only will it set the stage for what’s to come, by introducing the character of Aunt Esther—a former slave who is reportedly close to 300 years old, and has the power to “wash men’s souls.” Esther only appears once, in Gem, but she is referred to in several of the plays that follow. In fact, Fences is one of the few plays in the Century Cycle that carries no references to Aunt Esther at all, or makes reference to her home at 1839 Wylie Avenue, in Pittsburgh, the focus of Wilson’s final play, Radio Golf, in which realtors debate demolishing Aunt Esther’s historic home to make way for apartments and chain stores.

So kicking off the next phase with Esther herself would make sense.

But more than that, I would argue that, for all of the challenges of putting that particular story on stage, Gem of the Ocean is the most potentially cinematic of all of Wilson’s works. Though the play is set entirely inside Esther’s home, there are constant references to action taking place outside, with stories of a man drowning under a bridge after stealing a bucket of nails from a nearby factory, a massive fire that at one point engulfs the factory, one or two hair’s-breadth escapes in a wagon and the remarkable moment when Aunt Esther takes the troubled Citizen Barlow on a trip to the City of Bones, at the bottom of the sea, where the remains of slaves tossed from ships are lain to rest.

In the play, it’s merely described. But in a movie, the right director—and I’m putting my hopes on Washington—will finally be able to bring the City of Bones to aching, shimmering, heartbreaking life. That, I have to say, is something I can’t wait to see.