Last month, I received an email from the county telling me that I made a mistake in an article. Indeed, I erred.

Typically, the Pacific Sun would run a correction, and that would be that.

But Sarah Jones, director of the Marin County Community Development Agency, didn’t ask for a correction. We spoke at length about the situation, agreeing that it might benefit all involved to delve deeper and publish a second story.

In the original news article, which ran in the Pacific Sun’s May 8-14 edition, I wrote that the county had failed to inform Marin City residents when a private developer sought and subsequently received approval in 2020 to build a proposed five-story, 74-unit affordable housing project at 825 Drake Ave. This was inaccurate.

The county used four methods to alert Marin City about the proposed development before providing approval. From May to August 2020, these efforts included posting three signs on the property, creating a county webpage, sending out postcards to property owners within a 300-foot radius and holding a 10-minute workshop at a Planning Commission meeting on a weekday afternoon.

After the plans were approved in November 2020, a group of young Marin City residents working with the county requested that staff hold a public Zoom meeting to discuss the project, according to Tiawana Bullock, a group member. About 70 people attended the December 2020 meeting.

Yet most of the 3,000 residents in this unincorporated county area remained unaware of the plans until more than two years later, long after the project received the county’s approval. And when folks finally did find out that a large apartment building—the tallest in Marin City—was slated for their densely populated neighborhood with serious infrastructure issues, they were mighty upset.

So, what happened? Simply put, the message didn’t reach its intended audience.

Jones, who started working at the Community Development Agency in November 2021 and became the director two years ago, admits that the county fell short in its communications with Marin City by using a one-size-fits-all approach. And she wants to make changes.

“Outreach and what’s an effective way to communicate with people is definitely something that we’re struggling with and trying to work through,” Jones said. “It’s different in different communities.”

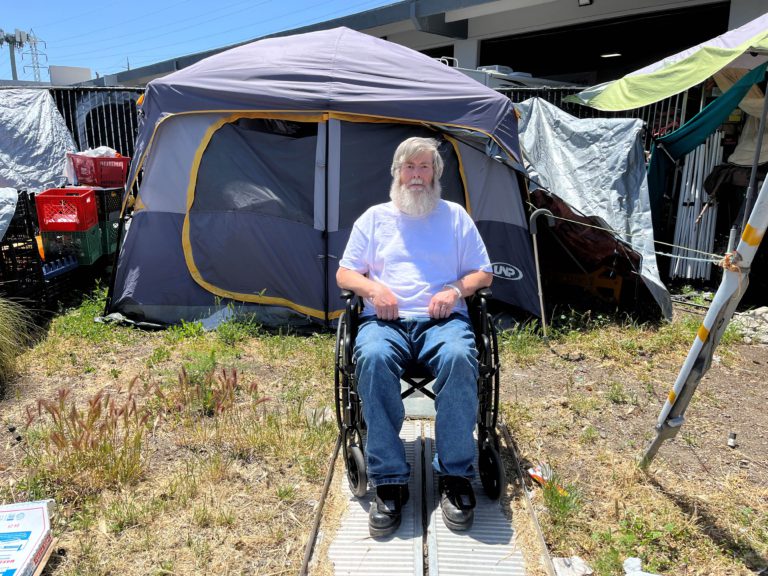

Marin City, a historically Black community, is now one of the most diverse areas in the county. While Marin ranks among the wealthiest counties in the United States, more than 9% of Marin City’s residents live at or below the poverty level, according to the latest census data. The median household income is far lower in Marin City than in the rest of the county.

Consequently, Marin City residents experience what is known as the digital divide—having less access to computers and the internet than the rest of the county. Digital literacy and language barriers also contribute to the problem.

Emails, online surveys and county website postings aren’t the best means of sharing important information with Marin City residents.

Ditto for public meetings held during the workday. Many residents don’t have the luxury of flexible work schedules.

“I understand that some people in Marin City don’t have the time,” Jones acknowledged. “It’s not fair to demand that somebody be a professional citizen to stay informed.”

Leaders in Marin City, including those who run nonprofit organizations and churches, say they know how to connect with folks. They do. I’ve attended countless standing-room-only events and meetings in the community.

“There are a variety of methods to do outreach to a population of 3,000 people,” said Felecia Gaston, founder and director of Performing Stars of Marin, a nonprofit serving Marin City. “Make it user-friendly. You can’t just do digital.”

Texting, disseminating flyers in different languages, going door-to-door, posting banners at the freeway exit and tabling in front of Target at the nearby shopping center top Gaston’s list. She emphasized that the community is small enough that these efforts have a big impact.

Golden Gate Village, a public housing project in Marin City, is home to about 700 people. Royce McLemore, who serves as the Resident Council president, pointed out that there are numerous homeowner and tenant associations in Marin City—all of which communicate with their members.

“The county could use those various organizations to get the word out,” McLemore said. “But nothing beats going door to door.”

It takes manpower to knock on hundreds of doors, and that’s not necessarily practical for the county. However, these community organizations regularly connect with their members, and the leaders who I spoke with want to help keep residents up to date on issues.

“We have a whole street outreach program,” Gaston said. “We are so good at it that I brag about it. Clipper Card contacted us specifically because we know how to research and contact people in Marin City.”

Rev. Floyd Thompkins of St. Andrew Presbyterian Church in Marin City believes the county’s first step is developing a communication policy with Marin City. According to Thompkins, some departments within Marin County, including public health and behavioral health, have made strides in this area.

“There’s no plan on the county level on how you talk to Marin City,” Thompkins said. “What is the procedural plan when something is going to affect Marin City? It’s always ad hoc. The county should do it for all unincorporated areas. Even if they develop that plan without us and tell us what it is, we will have an expectation of how they will communicate.”

Jones agrees that her department needs to proceed differently moving forward. But she also realizes that new policies won’t remedy what occurred in the past.

Ultimately, she says that the county would probably be in the same place about 825 Drake Ave. It’s not a good place either. Last year, Save Our City, a community group opposing the project, sued the county and developer to try to stop it. That lawsuit is wending its way through the courts.

It’s true that the county had no choice but to approve the project. When the developer submitted the project application, unincorporated Marin County was subject to Senate Bill 35 because it had not met its state-mandated housing production goals. SB 35, a 2018 state law, requires a streamlined approval process for multi-family housing projects that meet specific criteria, and 825 Drake checked all the boxes.

Still, one must wonder what might have happened if a significant number of residents were aware of the proposed housing project while the county was reviewing it, before the developer sunk tens of millions of dollars into the property. Instead of raising funds to pay for a lawsuit, perhaps the community could have bought the one-acre plot—the last buildable site in Marin City.