By James Knight

Even if you can’t find Sean Thackrey in Bolinas, you expect to find Sean Thackrey in Bolinas. He’s been called eclectic, eccentric and idiosyncratic, and that’s just in one magazine article. Add cryptic, enigmatic and even downright medieval, and you get the picture that the winemaker inhabits the outskirts of wine country proper—of course you’d be more likely to find such a character in a bohemian enclave like Bolinas.

Except that for many years, I could not find Sean Thackrey. Yes, he had a website, but even that was arcane: Much of the text is in Latin, Italian and Middle French from the scholarly winemaker’s personal library. An email went nowhere. I made a reconnaissance to Bolinas, poking around in the eucalyptus groves where the vintner was said to be ensconced with his barrels and his books, and making wine according to ancient recipes.

And it wasn’t just me. As novelist and wine writer Jay McInerney recently told the Wine Writers Symposium at Meadowood, for all his world travels, finding Sean Thackrey in Bolinas was one of the most confounding tasks. Thackrey must be the last vintner in the world who doesn’t send out regular press releases to tout his wines.

Then one day, there it was in my inbox: A press release from Thackrey & Company Fine Wine. What happened?

Whole Foods happened, for one. Thackrey’s lowest-priced and once slightly-less-than-impossible-to-attain wine, a red blend called Pleiades, got picked up by the behemoth grocer for its Northern California stores, which means that Pleiades must be on the shelf at all times. Thackrey ramped up production, hired a marketing assistant and an office manager, and, at their insistence, even became an enthusiastic participant on social media—which he used to call “antisocial media.”

A photographer and art history dropout, Thackrey co-owned a San Francisco art gallery when he founded a winery at his Bolinas home in 1981. He first sold wine to his friends at Chez Panisse and garnered early acclaim when his first official release was called “the best Merlot ever made in California, blah blah blah,” according to Thackrey, by a budding wine critic named Robert Parker.

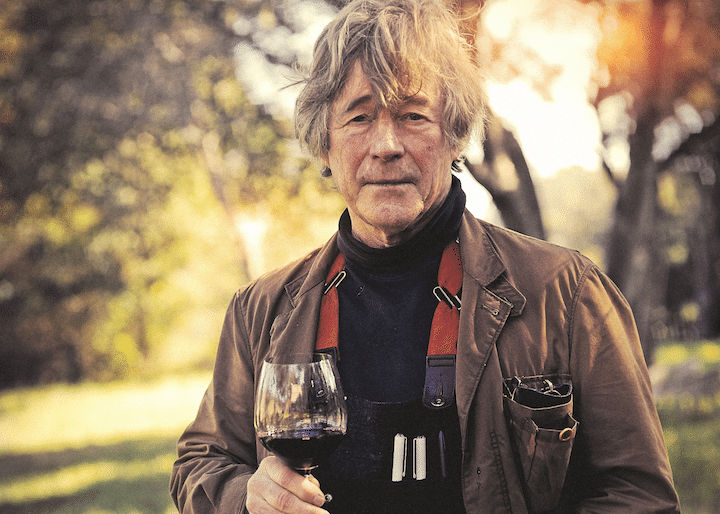

When I finally meet Thackrey, he bounds out of his Bolinas barn—a newer location that holds extra barrels and a few old redwood fermenters, and which is just a little more artistically bent than your average barn—and begins talking a mile a minute about the origin of Pleiades. Clad in a jean jacket and sporting a gray mop coiffed by randomness, Thackrey’s affable, academic quickness and vintage style are reminiscent of a radical campus professor with roots in the ’60s.

James Knight: From reading articles over the past decade or so, I would think people have this impression of Sean Thackrey as the reclusive, mysterious winemaker.

Sean Thackrey: People just get so enamored of that kind of simplification. The other one that I love is being called eccentric, just because I don’t do things the way [UC] Davis does them—it’s not eccentric in the slightest.

Knight: Would you say that your use of ancient texts is overemphasized?

Thackrey: Well, I think it’s a little overemphasized. Wine has really been made a lot of different ways. I don’t think people understand how different earlier wine styles are than what we now do—I mean just totally different—and yet they gave great pleasure. So I think it opens your eyes to the immense number of possibilities to make something that might be really delicious, using all sorts of techniques that we don’t even think of now.

Some of the most famous wines of Greece, for example, were cut pretty severely with seawater. The island of Kos was kind of famous for its wines, and apparently a shipment of wines was going to Athens from Kos, and when it arrived, there were two amphorae that were decidedly better than the others. The shipper was really interested in getting to the bottom of why these two were so much better than the others.

To make a long story short, it turned out that the crew had said, f**k it, we want some wine, so they broke into these amphorae and they took a bunch of wine out to drink on the boat and replaced that with seawater. And apparently that was so much better, that became a standard technique of making what they called Coan wine. I’ve never tried it, but it’s just an example of something that you wouldn’t dream of doing now. And yet you have to think that the people who made the Parthenon had a reasonable taste in wine.

Knight: What are some examples of ancient or medieval techniques that you do apply?

Thackrey: It’s more the idea of being open to different tastes in wine than just the narrow band that we’re now working with. I’m not advocating adding seawater to wine, but you at least might want to do the experiment just for the hell of it.

As I said, do you really think that the people who designed the Parthenon were sitting down and drinking absolute rot? It’s a little hard to believe; that’s not the way it generally tends to work. I just think it’s very nice to keep an open mind about what can actually work in winemaking, and I think studying ancient texts is a very good way to do that.

Knight: Most of the time when people talk about the ancient technique of winemaking that they’re doing, it’s just crushing, not adding stuff, and punching down. And they say, well, that’s the way it’s always been done. You’re saying there’s more to it than the bare bones?

Thackrey: Far more. Winemaking used to be far more invasive than it now is. Half of the old winemaking texts are ways to fake things, ways to add stuff, because there were so many ways for wine to go bad. After all, it wasn’t until Pasteur that people even realized—microbes were thought not to exist and there was a lot of sentiment that any suggestion they might exist was considered heresy at that point.

That’s what’s interesting about the history of winemaking, is how little of it was undisturbed. If you lived in the village of Nuits-Saint-Georges, you could get some pretty much undisturbed wine; if you lived anywhere else—I mean, that Burgundy was going to be put through so much bullshit by the time it ever got to you, that it would be pretty much amazing to talk about it as just being the real thing straight from the source, not being touched by anything but pure virgins or something. It was unbelievable.

So a lot of those texts are meant to be very practical, which is what makes them interesting to me. Because they actually go into the detail about what you’re supposed to be doing. And some of the detail was very surprising!

Knight: For example?

Thackrey: If you go anywhere in Burgundy they tell you it’s all been done exactly the same way since the seventh century or whatever—the pretense is that we’re just doing the same old thing; wine is made in the vineyard; we don’t really do much of anything, and so on.

Well, the first text that really goes into great detail on winemaking in Burgundy is from about 1831. And it was by a Dr. Morelot who owned some major estates in the Côte d’Or, so he knew what he was talking about.

I was just very struck, for example, by where he talks about how long a great red Burgundy should be fermented. He said it should be on the skins for something between 24 and 36 hours. Hours? You know, that wouldn’t be enough to make a rosé nowadays. I mean, our Fifi is on the skins for much longer than that.

Knight: What about the cold soak?

Thackrey: I use a different version of the same sort of idea, and I’m the only one I know that does that, although it used to be very common. That is definitely an idea that I would not have had if I did not get it from old books. The first mention I have of it is from the Greek poet Hesiod—that would be eighth century B.C., so that’s going back quite a ways—and it goes as a leitmotif all the way up through the entire history of winemaking until the late 19th century. That was the idea that you get the grapes off the vine, and then you simply put them some place and let them rest for a while before you then crush them and make them into wine. We do that now absolutely as a matter of course.

There’s no question whatever that the wine produced from fruit that had just been allowed to sit for a while was simply better. And it was better, because it was more harmonious. It had an unusual sort of quality about it.

Nobody in classical cider texts ever talks about taking apples right off the tree and fermenting them. They would let them sit in a pile. It was called “sweating” the apples. They would sit there and they would be practically rotting, a long time … And then they would crush them and make them into cider. And it was very much the same idea [with grapes]. It was meant to improve the taste.

That’s the kind of thing that is, I think, a legitimate use of early texts, and it certainly was a surprise to me.

Knight: Have you come across anything regarding the Medieval Warm Period, when temperatures were maybe two degrees warmer until the 1400s? It struck me that varieties like Pinot Noir became celebrated during that time. So were they making the California-style wines that people talk about these days, or what?

Thackrey: Who the hell knows, but that’s just the fad that we’re in now—the low-alcohol fad. It kinda gets to you after a while, particularly if you read back historically. All of the great vintages—the vintage of 1811 or the vintage of 1945—they were all the hottest years around. That’s what everybody said—the wine had concentrations we’d never seen before. Well, now we hear about the French palate, the American palate, fruit bombs and crude, over-extracted wine—and I’m so tired of that. I mean, there are ways to sell wine, and that’s one of them. But ripe fruit is ripe fruit.

Yes, fruit will be ripe at different points for different kinds of wines. Obviously, fruit that’s made into Champagne is perfectly ripe for Champagne; it’s certainly not ripe for Amarone.

If you think about it, the difference between 15 percent and 13 percent is 2 percent. Well, 2 percent of 750 milliliters is 15 milliliters. If you look at 15 milliliters, that’s the difference in the amount of alcohol in a bottle of wine at 15 percent vs. 13 percent. Do you really think that’s just going to totally unbalance everything and wreck the thing and make it into this horrible, hot finish, chemical-tasting wine? It’s crazy.

To me, the classic argument is, OK, so you can’t drink port, because it’s 21 percent alcohol, right? It’s got a hot finish, right? Ah, well, no!

Knight: I hear people talking about how they want a wine with a “sense of place,” and that it should taste like it “comes from somewhere.”

Thackrey: Oh, I’ve heard that so many times. If you wanted to talk about it as being a cultural thing, then I wouldn’t have any problem with that at all. For example, let’s suppose we’re sitting here at the table with an old guy from Morey-Saint-Denis and we serve him a Chard, and he says, “That doesn’t taste at all like our home cooking, that doesn’t have the sense of place that I want it to have, that doesn’t taste like Morey-Saint-Denis to me.” Well, that’s a cultural thing.

Knight: It’s a personal history.

Thackrey: It’s a personal history, absolutely. That’s home cooking, is what it really is. That’s perfectly valid; there’s nothing wrong with that, that’s great. But for people to invent this whole idea that somehow the subsoil of the Morvan Forest wants to express itself in a glass of wine, I mean, it just sets off so many short circuits for me, it’s very, very hard to stay entirely polite.

Knight: I’ve seen this applied to recently developed vineyards.

Thackrey: Oh, sure, and you go on the website and all you see are pictures of dirt!

I don’t understand it in the slightest. The idea that fruit grown in different places tastes different is hardly revolutionary. The point is, somebody has to do something with this. And what they do with it is going to be what bats last as to how it winds up tasting.

After all in so many cases, I will be buying part of a vineyard’s production of Sangiovese, say, and somebody else will be buying the rest of it. So we’re both making wine from exactly the same grapes. And very often we’ll harvest it on exactly the same day. And we will wind up with wines that are radically different from each other. And it’s not that either one of us is some mechanically minded winemaker that just ruins everything into the same stuff; it’s just you make different choices as you’re going along, as a cook would. Nobody would expect that two different chefs working with the same source of chicken would wind up making chicken that tastes the same. I mean, of course you wouldn’t think that.

It’s a matter of what people want to believe. The part that I don’t like about the whole thing with terroir is the part that is simply in bad faith. In other words, it’s absolutely to the economic self-interest of people that own vineyards to attribute the quality of the wine that results from that vineyard to the real estate that they own. This is very bankable.

It’s like having a restaurant that’s called Chez Jacques and Jacques dies—well, what happens to the restaurant? Well, that’s very much true with winemaking. So obviously if Chateau Margaux can sell people on the idea that it’s because of the real estate that is owned by Chateau Margaux that Chateau Margaux tastes the way it does, they’re way ahead of the game.

Knight: Do you feel that at this point people will keep coming back for your wines for the name, or do you really have to keep up the innovation and quality?

Thackrey: Well, I do. Nothing ever goes out of here that I don’t absolutely like, completely. And I mean in the sense that I want personally to drink it as often as possible. That is a rule about which there is no negotiation whatever. We even call the catalogue that we send out to our mailing list, The Catalog of Reliable Pleasures. Because that’s what I like to think of them as being.

If someone feels just like a glass of Pleiades, they’re going to go up there and take down the bottle and pour themselves a glass of Pleiades, and you know, they’re going to like it! They know that. So consistency I think is extremely important, particularly if you do as much experimenting as I do.

I think people still have to feel that the end result is going to be something that I actually, really, no kidding, feel was pretty terrific.