by Mal Karman

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness … we had everything before us, we had nothing before us …”

So wrote Charles Dickens long before a Marin businessman named Don McCoy dropped out and created a utopian community at Rancho Olompali in 1967, a time and a place that had many convinced they were magically living in heaven and later found they were heading directly the other way.

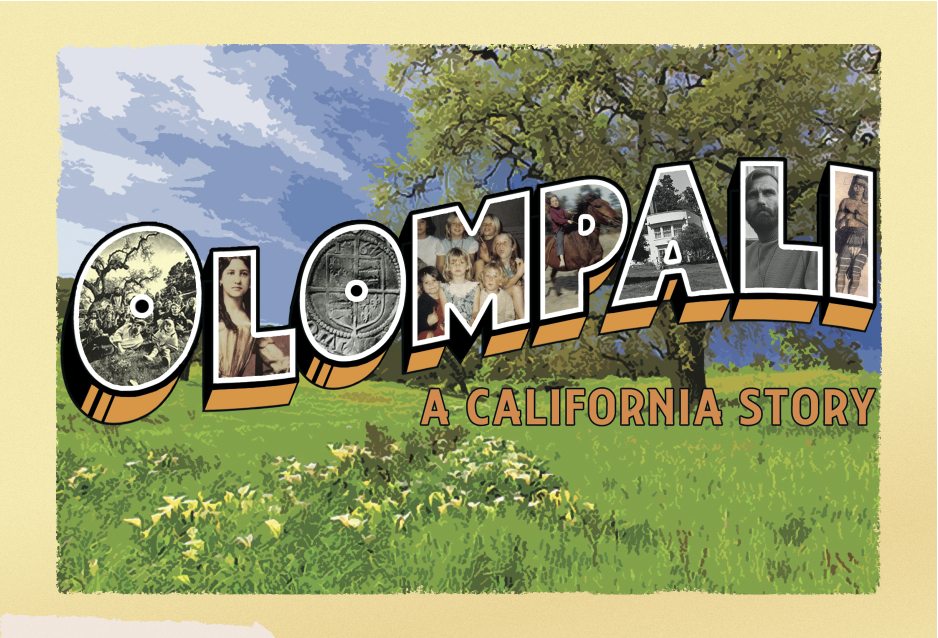

This is a big part of the tale McCoy’s oldest daughter Maura will tell in the feature documentary, Olompali: A California Story, that she is producing with partner Gregg Gibbs.

“Dad had inherited $500,000 from his family,” Maura says. “That’s like $4 million today. He and his friends, who all had kids, started looking for a large house with a large yard. A realtor [going by the tag Codfish Carrier] showed them Rancho Olompali, a few miles north of Novato, and everyone fell in love with it! It’s one of the most beautiful places you can imagine, out in the country, 690 acres with a 26-room mansion for maybe $1,000 a month!”

What’s not to like? A mountain rises behind you to 1,558 feet with stunning views. The land is filled with oak and bay trees and a storied past. And the silvery waters of the bay sit right in your sightline.

While it didn’t start out to be the quintessential hippie commune of the ’60s, when parents and their kids want to live as an ensemble, that’s what you get. It became even easier when Don, the nucleus of the Chosen Family, as they chose to call themselves, “wanted people not to stress out by working at a job. But if you had talent, he wanted you at the ranch; you pitched in with labor,” recalls Noelle Barton, who with her mother Sandy [a San Francisco nightclub singer] was part of the original core group. “We had an awareness and sharing mentality.”

Maura, who now lives in Marina del Rey [Los Angeles County], reflects on this and says, “As I got older I kind of put Olompali behind me. I rejected hippie things and went back to a more conventional lifestyle. We always reject what we’ve been raised with, and I wasn’t really that interested in it in my 20s or 30s … Then Gregg and I came up here and saw an exhibit at the Marin History Museum about Olompali and he thought, ‘Why don’t we make film about this place and tie it in with your experiences and your father’s history there?’”

Over several months in 2013, a Kickstarter campaign raised more than $45,000 for principal photography. Now in post-production, the film, Maura says, presents them with the daunting challenge of simultaneously trying to raise finishing funds and getting the film ready to submit to the Mill Valley Film Festival. “I have to say there are always periods of doubt with a project of this magnitude,” she says. “Obviously there have been some [momentum] lulls, we don’t have a firm completion date, or release date, and there’s this Grateful Dead documentary that’s being produced by [Martin] Scorsese. And they got [senior state archaeologist] Breck Parkman to walk around and talk about the band living at Olompali. Hey, that’s our guy!—they’re stealing our thunder. It can be discouraging, but now I feel this will actually benefit us. If that film is successful, it can generate interest in ours.”

As to the challenge of digging up material from a long-ago era, the fact that so many kids experienced the commune made it possible to get first-hand recollections 47 years later. “We, who are still alive, are in touch with almost everyone except a few who we have lost track of over time,” Noelle Barton says, “and I would say at least 80 percent of the founding families and their kids are all one family to this day.”

“Unfortunately, we don’t have my dad here to tell his story,” Maura says, “but he put it on tape! He went to the Marin Civic Center library in 2000 and did a whole oral history that they recorded there. We have an archive of a radio show he did. These things keep coming out of the woodwork. One person had a whole cache of newspaper clippings—including a story in the Sun called ‘Nirvana in Novato; We interviewed Carol Garrett last year—she’s since had a stroke—and she is one of our best subjects. She’s the one who had a nude wedding at the ranch and she pulled out an album loaded with photographs. These things are priceless!”

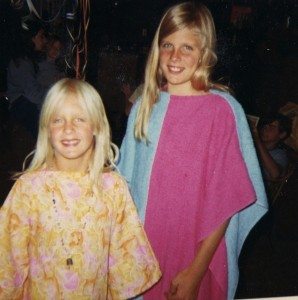

When the Chosen Family set up house at Olompali and was finished choosing (at least temporarily), by most accounts there were about 10 adults, 15 girls and four boys: Don and his three girls, Maura, Dana and Mary; Sandy and Noelle; Bob and Sheila McKendrick (who would later divorce Bob and marry Don), their two daughters and son; and Buz Rowell, their de facto ranch manager. They soon added the likes of a pot-smoking nun, Sister Mary (now Mary Norbert Korte) and a pot-smoking elementary school teaching principal, Garnet Brennan, whose 30-year career was erased by the Nicasio school district after she admitted to smoking weed.

Six of Sister Mary’s poems appeared in the book Women of the Beat Generation, including one titled, “There’s No Such Thing As An Ex-Catholic.” Meanwhile, Brennan, whose termination was a national news story picked up by LIFE magazine, set up the dining area at the mansion as the classroom of the “Not School.”

“We had displays, supplies, books, tests—yes, she tested us,” remembers Maura McCoy, who was 10 at the time. “She was a professional educator and a great person to have there.”

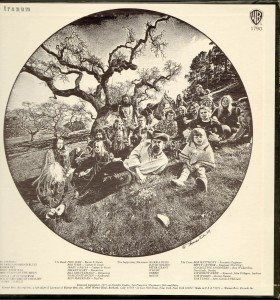

“We had a Montessori-type school,” Barton says. “Kids in the real world didn’t have their own horses or an oversize swimming pool or the freedom to choose their own bedtime. Kids even got to pick what color to paint their room. You can’t dream of a life like that. At my age [then 17] all boundaries and restrictions were removed. You don’t have to go anywhere. Or do anything. Music came to us [including the Grateful Dead, who lived at the ranch during the summer of 1966, and were close enough with Don and Sandy to just drop in on weekends].”

Others who supposedly passed through could either be found in a Grammy lineup or a police lineup: Janis Joplin, Grace Slick and Jefferson Airplane, a 5-year-old Courtney Love, Nina Simone, Lou Gottlieb (of the Limeliters), Bill Cosby, Ken Kesey, Jack Kerouac, Hells Angels and Charles Manson. The back cover of the Dead album Aoxomoxoa features a photo of Jerry Garcia and commune members, including Maura McCoy, among the trees at Olompali.

“Everything was in the moment,” Noelle Barton recalls, “and you had a choice, a lot of freedom and merriment. You might make some wrong choices along the way because you didn’t have enough [life] skills … There were people who showed up later to take advantage of those freedoms, but not at the beginning. We worked hard, making meals three times a day for 50-60 people, shopping for food, cleaning up after. But work isn’t a chore when you’re sharing with people you care about—six or more of us washing dishes together and laughing and talking—it’s more adventure than chore. We milked our own cows, milked our own goats, fed and groomed horses, tended the garden.”

“It was a special and wonderful life,” Maura says. “Just a lot of freedom as children. Pot was definitely made available to us, but it was entirely up to us. On occasion like a party anyone could have LSD. I tried it, didn’t like it. Nobody thought pot was harmful, even though some of the younger kids who have kids of their own now say, ‘How could they have done that?’ But it was a different time.” At Monday night meetings of the Family, each adult drew a child’s name out of a hat and would “adopt” that boy or girl for the week. “We were collectively parented,” Maura says. “More specifically, to make sure each child was being looked after, we were assigned each week to a specific adult. They just wanted to experiment with different ways of parenting. I wasn’t missing anything, any more than any child of divorce who misses a parent.”

Maura’s sister Mary concurs. “I was only 6 at the time,” she says. “[But] that was a difficult period for all of us. You suddenly lose your place in the universe with regard to your mother and father, and when I lived with my parents, I had a bedroom—and all of a sudden I’m sharing a big space with many other kids in the mansion, but new friends trumped the rest of it.”

Maura the filmmaker has no illusions about making money with a documentary. “This project is a labor of love,” she confesses. “It is my way of remembering my father [Don McCoy died in 2004]. It is also a tribute to a place that now holds a special significance in my memory and in my heart, and which has an incredible story of its own.”

According to archaeologist Parkman, Native Americans had been there for between 1,500 and 4,000 years. “If you lived at Olompali, within minutes you could catch fish or deer, you could grow things, you were close to water—it would be like living in the parking lot of Trader Joe’s today, never having to worry about food.”

As American settlers tried to steal California away from Mexico, the first battle of the Mexican-American War erupted on June 24, 1846—The Battle of Olompali, right here in Marin, and the only clash of the Bear Flag Revolt that resulted in casualties.

One of the most amazing finds on the property is an Elizabethan silver sixpence dated 1567, the time of Sir Francis Drake’s landing in Marin County. Perhaps he stopped by to trade with the Miwok Indians, via a route we’re reasonably certain did not encompass Highway 101. See, even then you couldn’t count on it.

How the land passed from the Miwoks to a land baron to a dentist and others, eventually to the University of San Francisco and, ultimately, to California and its current status as Olompali State Historic Park is juicy history that McCoy and Gibbs plan to harvest for the film.

As part of the communal template that was being forged there in ’67 and ’68, new people anxious to be part of it all had to be voted in. One who did was Peter Risley, a 20-year-old freelance photographer hired to shoot photos for a Pacific Sun article on what one reporter called “The White House of Hippiedom.”

“After I joined the experiment the photography dropped away, due a lot to my immaturity,” Risley says. “I was a good idealist, but not a good businessman.”

Buz Rowell remembers that Risley “hit it off with everyone and he sort of took over the garden. The kids and adults helped him and, because animals dumped their stuff there, it was really productive. We grew chard, corn, beans, tomatoes, cukes, squash, yeah marijuana, but not too much, because people were always bringing in gunny sacks of Acapulco Gold.”

We tracked Risley down in Kapaau, Hawaii, where he is now an award-winning organic farmer with a pretty sober view of life, now and then. “It was there I decided farming was what I wanted to do—it was needed and I could do something for the world. Things that made Olompali relevant—it’s now intensified. We’re in trouble because of the way we relate to the earth and each other. Our society has yet to open up to what we were trying to do back then.”

He recalls the press gleefully descending on the ranch, apparently anxious to puncture holes in what many perceived to be the absurdities of the freethinking counterculture.

“The media stuff was always happening, which created a negative situation. We weren’t ready to deal with it. We were dealing with our personal lives. A lot of stuff that happened was imposed on us. I really liked Don a lot, and I saw things that happened to him that reverberated with all of us. He was a man who landed in a hurricane. Don’t forget that period was right in the middle of revolution—this great change in America and particularly on Haight Street—and the feeling was, ‘We’re it!’ But there was not a snowball chance in hell that [the commune] could survive, and that was our own fault. Because of the publicity, he was getting letters from people looking for answers and wanting to come and live there, people trying to use him. We just got crushed by reality and our own naiveté.”

About seven months into Don McCoy’s communal life, in the summer of 1968, his father asked his grandfather to put Don’s inheritance into conservatorship “so he doesn’t piss it all away.” Maura says, “Dad didn’t fight it. He’d become all hippie by then and actually felt the money was a bit of a burden.” But they did offer him enough to join Sheila and Buz at the Worldwide Spiritual Conference in India, though that may have sounded the death knell for the ranch.

In November 1968, while they were still in Calcutta, someone left a gate open at Olompali and a horse ran down the driveway that led directly to the freeway. A second gate [at the bottom of the hill] was usually kept closed, but that, too, was open and the horse ran onto Highway 101, causing the driver of a semi to jackknife as it slammed into the animal. Both the horse and the driver were killed.

When the group returned to California from India, Buz Rowell says the structure of the commune had been changed by Bob McKendrick. “The ranch was never the same after that,” he remembers. “A lot of people had joined up since we’d been gone, people living up in our hills. You’d look at them and ask, ‘Do they live here?’ and someone would say, ‘Duh, I dunno.’”

In January of 1969, narcotics agents made two raids at the commune, busts that Maura believes were the result of an informer in their midst. When the narcs demanded to know who owned all the marijuana, Don replied, “It belongs to God. I just smoke it.” Charges were eventually dropped.

Not long after, in the early morning hours of February 2, old and faulty wiring caused a raging electrical fire. “From the highway you could see flames leaping out of windows,” recalls Noelle Barton, who had been working a light show that night. “When we shot up the road, the fire trucks were already there, but they weren’t doing anything. They were waiting for the captain to arrive to give orders, but he had had a heart attack on his way over.” Though everyone got out without injury, a dog, two cats and a parakeet were burned to death and the blaze gutted the 150-year-old, two-story mansion.

After the fire, Olompali was hanging on by a thread. “Watching it fall into shambles was very sad,” Rowell says. “It was nothing like the joy when we started. There were no family meetings anymore or sounding things out. Don was losing touch with reality and that was dividing people, too. The ranch fell into the hands of [the late Bob] McKendrick, who I didn’t get along with—there were more drugs, PCP, speed, hallucinogens. The school was not there anymore—children had gone back to public schools. They started moving out; that’s what was missing, it just wasn’t there anymore. Things were deteriorating. It became authoritarian.”

Don McCoy had a breakdown and was, according to Maura, at Marin General under observation in the mental ward. Then, signaling the final tragic note of a movement that ultimately had witnessed the last of its music in the air and flowers in the hair, two toddlers—2-year-old Nika Carter and 3-year-old Audrey Keller—were pedaling a tricycle along the edge of the unfenced pool and fell in and drowned.

“I was in the workshop in the dormitory when it happened,” Rowell remembers. “People started screaming. I came out and saw everyone racing around frantically trying to start cars.” No one could get any of their wrecks to fire up and by the time they were able to get the girls to a hospital in a neighbor’s truck, it was too late. “On that day, my dad looked out the [hospital ward] window and saw people from Olompali rushing in,” Maura says, “and, later when he heard what had happened, thought he would be blamed for this.”

Outraged county officials had had enough. They charged up to the ranch, found dozens of building code violations, and had landlord USF order everyone out within 30 days.

Although that was the end, there are connections to that time and place by members of the core family that apparently cannot be severed. Rowell, who now lives in a trailer park just south of Jenner, says, “Whenever I’m going south to San Francisco, I always stop at Olompali and take a solitary walk around and remember how it used to be. Although we live in different places, I have kept in touch with a lot of our people for many years.”

Maura McCoy says that her attachment to the relationships she formed back then has deepened the deeper she gets into her production. “I was definitely exposed to different ways of thought, to people who had yearning for peaceful ways of living, collectively with others. It gave me a more liberal and progressive outlook on life in general, introduced me to organic foods, to eastern religion, to farming, to alternative theater. Maybe today that sounds almost mainstream, but we were really counterculture then. And I embrace the emotional honesty that my father always expressed, and the straightforward, generous spirit that made him a well-loved man.”

Noelle Barton puts it this way: “It is my lifelong dream to manifest this documentary so, once and for all, the story can be told by us, correctly, because it was our life!! We’re definitely not going to whitewash it—mistakes were made along the way. It was the rise and fall of a utopian society, with an ending that, to me, was a big shock. But the film, which will be narrated by Peter Coyote, is just about recording history—and we have a lot of colorful history. It was spectacular and obviously beyond the comprehension of those people who didn’t live through those days … but even with the bad experiences that befell us, it was still one of the greatest adventures and I feel blessed to have been there then. Physically we lost the ranch but, as the film will show, we never lost each other.”

Ask Mal if he’s reached Nirvana at le*****@********un.com.