by Steve Heilig

For a few years in the 1970s, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were America’s Beatles—the most popular rock “supergroup” of them all, known widely as “CSNY.” And Graham Nash was the band’s George Harrison—he was the Brit in the group, and even looked like “the quiet Beatle”—with Neil Young and Stephen Stills being John Lennon and Paul McCartney, leaving David Crosby as Ringo Starr—which doesn’t quite work, as he says below, but close enough. They played the original Woodstock festival, sold out 100,000-seat stadiums and their songs were No. 1 anthems for a generation. Each of them had simultaneous, successful solo careers, but the band melted down in a blaze of excess, ego, addiction and infighting—only to reunite again and again to this day. All four of the members have been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—twice. And what music they have made, together and on their own.

Nash was no newcomer to rock stardom when he helped form CSNY. Born in a bombed-out Manchester slum in 1942, his passion for rock and roll was ignited by Elvis and the harmonies of the Everly Brothers. He was singing onstage for cash by his early teens, and his first real group, The Hollies (named for Buddy Holly), was among the most popular British bands, and a star of what became known as “Swinging London.” Nash drove a Rolls-Royce, and opened not only for the real Beatles but for The Rolling Stones and Little Richard, whose band at that time included a young Jimi Hendrix on guitar.

But by the late 1960s, tensions in The Hollies and in Nash’s young marriage led him to flee to California, not only into the arms and Laurel Canyon home of new flame Joni Mitchell, but into his lifelong partnership with Crosby and Stills, which he has called both the joy and the bane of his existence. He calls his musical partners “brash, egotistical, opinionated, provocative, volatile, temperamental and so f____g talented.” Crosby, Stills, Nash (and sometimes Young) is a musical unit that has endured sporadically for decades, earning Nash fame, fortune and pretty much every award popular music offers. He has sung for presidents, and in an unlikely pinnacle for a kid from the slum, Queen Elizabeth made him an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). Notified of this, Nash, at first, thought it was David Crosby playing a practical joke, and with an OBE being just below true Knighthood, Nash reflects, “Would I have to suck up to Sir Paul and Sir Elton? Not in this lifetime.”

All of this and much more is told with great recall and candor in Nash’s 2013 autobiography, Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life, which is full of yes—sex, drugs and rock wildness, but wherein Nash also comes off as the most grounded of his famous partners. “It’s all about the music,” he proclaims over and over, and it must indeed be, for he relates much tension and outright conflict between himself and the mercurial Stills and “the strangest of my friends,” Neil Young. Nash often has taken on the role of peacemaker among the prickly group, but his best friend and former longtime Marin resident Crosby seems to have given him the most unintentional grief, by spiraling into severe cocaine and heroin addiction, entailing extreme dishonesty, non-repaid loans, bankruptcy, prison and near-death experiences, all of which Nash painfully endured with the devotion of deepest friendship. Theirs is an inspiring tale of lifelong mutual support and survival, and Nash still calls singing with Crosby and Stills “the best high I’ve ever had.”

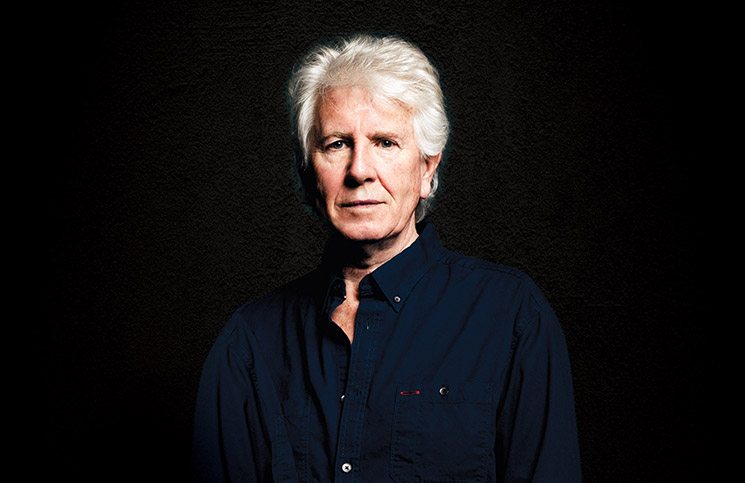

Long a devoted family man with three grown kids and two grandsons, Nash, at 71, is still trim and spry with a twinkle in his eye, and divides his time between Los Angeles and Kauai when not on the road with various musical partners. A committed longtime activist, he has lent his fame and talents to many causes—environmental, political, anti-nuclear, human rights, public health (including vaccination), anti-war movements and more. But he has had another longtime passion since childhood—photography. He also paints and sculpts, but the camera seems to be his favorite tool after the guitar. “From the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with taking pictures,” he writes. “And not just any old snapshots but pictures that captured something significant, something insightful about the subject.” This second obsession, after music, has resulted in his large collection of other noted photographers’ work, a book of his own and others’ shots and exhibits in major cities and galleries—including the one currently on display at the Mumm Napa winery’s Fine Art Photography Gallery through Sunday, May 31.

*****

Let’s start with your photography. In your book you recall being very into cameras since you were 10 years old. What drew you to it?

I was looking for stuff that interested me beyond the “normal.” I realized that I saw things a little differently than my friends. And I think I kept doing that.

Have you always shot in black and white?

Yes, but now I do both that and color, only because of digital cameras—what I do is shoot color and then put that into black and white using conversion software that is part of my own company.

You’ve said that you try to blend in and not be part of any photograph you shoot.

Yes, I don’t want my presence to be affecting the photograph I am taking. It makes one self-conscious—I know when I am being photographed myself. I know I want to look like Elvis or somebody—that I want my best side forward. Because we’re supposed to be cool, and we have ego. And that ruins the picture.

On that note, you wrote that you’ve always wondered if you were cool enough; that “I’ve always had trouble with my coolness quotient.” Even when you were mobbed onstage and hanging out with The Beatles and Stones and Dylan?

Yes. I never thought I was cool. I’ve always tried, but I’ve never made it.

You think that comes from your poverty-stricken childhood?

Must be. I’m a very ordinary man in many ways. I know I do some things special, and I don’t want to ever lose sight of the fact that I am just incredibly grateful to be here, to have done what I have and still do. I’m very lucky and I know it.

In your book you say that you are no genius, but it sure seems like you hung out with a few of them, and maybe some of that rubbed off.

I’m certainly no genius. I’m good at some things, but listen, the first thing I did when I moved to this country was move in with Joni Mitchell. Now that should make just about anybody humble about making music.

Well, I’m no Freud, but there seems a certain irony in that your father was arrested and imprisoned for stealing a camera when you were still quite young. Do you think that has something to do with you being so devoted to photography?

Of course. It has everything to do with it. I’m taking these photographs for me and my father. I’m extending his life by expanding what he taught me about the magic of photography many years ago, when I was 10 years old. He stood me before a crude enlarger and this blank piece of paper and 47 seconds later this image appeared out of nowhere—now that’s magic, and I’ve never forgotten it.

Have you been inspired by any photographers that you most admired and even collected?

Oh yeah. There are several—I love Diane Arbus and her sense of dark humor and her courage to face some of the subjects that she did. In fact, the very first image I ever collected was her [“Child With Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park”]. At a photo auction once, where all the VIPs and moneyed collectors come to preview things, I was there with a glass of wine and a guy comes over to me and goes, “Do you know who I am?” I have a pretty good memory for things and looked at him and said, “No, I don’t think we’ve met.” And he said, “Oh, yes we have,” and I’m thinking, this is getting weird, you know—“Hey, security?”—and he says, “I’m the boy in Central Park.” He was by then about 40 years old, and I wanted to know what had happened for Arbus to get that angry photo of him. He told me he would take all his toy soldiers to Central Park but one day he pissed his mother off and she wouldn’t let him take any of them, just one thing, and he took that hand grenade. And he said this little lady in black came up and said, “Son, can I take your picture?” And that was it.

You don’t seem to shoot nature photos, like Edward Weston or Ansel Adams, but focus on people and odd moments …

Right, you have to have incredible respect for their ability and masterpieces, and I’ve even collected it, but it’s not the kind I take. People do like to see shots of some of my friends, but I concentrate more on surreal kinds of moments and disappear into those.

So do you have any particular memories of Marin?

Oh yeah, are you kidding, did you ever eat at El Paseo? Crosby lived in Mill Valley forever and we used to eat there constantly. It was fantastic, and the wine selection was unbelievable. [Laughter.]

So, as for music, I loved the story of you as a poor British kid getting completely turned on by Elvis and the Everly Brothers …

Yeah, but probably even more, Buddy Holly.

Yes, and so much so that your first real band was named after him. And with The Hollies, you had many hits and were chased by girls and screamed at and all that hysteria at an early age. How did that affect you?

Well, that whole thing about playing for half a million people with CSNY and all that rock and roll stuff— by the time I got here I’d already been through all that, and really didn’t give a s__t. We’d had 16 Top 10 records over there, so I could sing “Guinevere” with David and one guitar in front of 100,000 people, no problem.

In fact, you were trying to get away from all that “stardom” madness when you left England and The Hollies, and ironically you wound up in something much bigger here. Try this analogy on—I was thinking of CSNY as the American Beatles, with Young and Stills as Lennon/McCartney and you as George Harrison, but that leaves Crosby as Ringo and the analogy kinda falls apart there …

[Laughing.] Oh, it falls completely apart there for many reasons. I mean, for one thing, have you ever heard David play drums? No, no, no.

But I wonder if your previous experience with stardom in The Hollies kind of inoculated you against the really tough struggles all of your CSNY bandmates seem to have gone through.

Yeah. Good point. And the truth is, I’ve always been much more interested in the music than any of the other crap that goes on around it. All I really have wanted was to touch people’s hearts and minds with our songs and singing.

And you wrote that singing harmony with Crosby and Stills has always been the greatest high of your life.

Absolutely. Again, how lucky for me, right?

As for music nowadays, the Grammy Awards were on last night, and it was pretty much all appalling to my ears and eyes. What do you think of the most popular stuff now? It seems to me there is just something missing …

Er, yeah, it must be melody and message? I mean, with today’s music you can certainly shake your ass, and nothing wrong with that. But I’m a fan of great lyrics—I want to be able to hear a song, and then walk away singing it, to be affected and remember it. But a lot of modern music just doesn’t move my soul at all.

Does that make you feel old to say that?

Only in that exact moment when I just said that! [Laughing.]

Another difference I see and hear is the blatant, constant self-promotion and bragging, about being rich and all that. Maybe it was there before, but not like this?

It was there, but not like now, right. You know, in a way Woodstock was the beginning of the end, when corporations realized that they could sell stuff to millions of kids in new ways—sneakers, soft drinks, whatever. All of a sudden money raises its head everywhere in a different way. Don’t get me wrong, it’s nice to get paid well to do a show so you can pay your roadies and everybody, but it’s gotten out of control. I think it was blatantly brought to my attention when we went back to the Woodstock 25th anniversary show in 1994 and they were charging $12 for a bottle of water to a quarter-million kids on a slab of concrete—and then they wondered why they were getting upset and things went bad?

Locally, we had Bill Graham, who made the music into a paying business. You knew him well, I think.

Yes, and he paid you fairly. Bill used to piss off a lot of people but he was always great with me—very kind and fair.

He was also big on doing benefits for good causes, like the Haight Ashbury Free Clinic and so forth. You’ve long been very involved in philanthropy and benefits, too. You’re a longtime activist on many issues. Why?

I think it just comes from wanting to give back. Again, I’m this kid from Northern England, and look what I’ve been given. It shouldn’t all be happening to me, but it has. But then you have to prioritize your time and money, because we get asked to do benefits by the million. So I’ve asked myself, what are the three things most important to me? And the answer has been the planet, the fate of our kids and our environmental health.

Environmental health as opposed to that of the planet?

Yes, because regarding the planet, if every single human being dropped dead this instant, the planet wouldn’t give a s__t, it would keep spinning and something else would take over. Environmental health is how what we are doing is affecting our health—between environmental pollution on many levels, we face a lot of problems.

You wrote about overpopulation, too, and not many environmentalists even want to talk about that, even though that underlies so much environmental distress; the projections are very bad and there’s no denying now that we are in big trouble.

They don’t want to talk about it, because you know why? Because the response is often, “Wait a second, let me get this straight—you want me to stop f___ing?” Sorry, never gonna happen.

So beyond providing contraception, what can be done?

Well, for instance, the Chinese have done their share for the world by not bringing into the world 300 million more Chinese this year. And they have an interesting point, with their 1.5 kids per couple policy, even though it may be in trouble now and is of course very controversial, they say, “Wait a minute, we didn’t bring 300 million more people into this world, that’s our contribution,” and it’s a good point. In any event, I wrote my first population song in 1964 with The Hollies and just called it “Too Many People.”

You also once did a benefit for child immunization efforts. Have you heard of the controversies regarding that, and the recent disease outbreaks? It’s a real problem here in Marin.

Yep—I’ve got that problem going on in my own family! I think we need to get more and more science into this, to defuse the link between vaccination and autism, to bring down that evil myth. I’m willing to do my part to help with that if I can.

Ask Steve what his favorite photo is at le*****@********un.com.