By David Templeton

Most mornings at the Morgan Horse Ranch in Point Reyes, one can hear thousands of birds in the branches overhead, but today—just moments after a short, light rain—the trees are all silent. A black cat appears in the door of the barn, takes a careful glance to his left across the empty exercise yard, then carefully makes his way around the building, hugging the barn tightly before disappearing up the steps into the tack room. From across the pasture, the distinctively cheerful hey-huh-hey sound of horses in conversation floats in on the cold, moisture-heavy breeze. Save for a few work-engaged volunteers, the place is almost absent of human beings.

“A lot of people don’t even know the ranch is up here,” says Phil Straub, the manager and chief horse handler here at the historic ranch at the edge of Point Reyes National Seashore. Though the sprawling 30-acre spread is just a four-minute walk from the heavily trafficked Bear Valley Visitor Center, even on the park’s busiest days only a trickle of visitors notice the simple sign—“Horse Exhibits”—and find their way up the road to the tree-shaded haven at the top of the hill.

Between rainstorms on this damp January morning, as the sun turns an array of wet, glistening posts and shallow puddles into shining mirrors, a pair of volunteers carry supplies from one end of the ranch to the other, smiling as a lone visitor trudges up the hill toward them. Meanwhile, out in the field, a handful of horses stand out near the fence, barely moving, none of them large but clearly strong and powerful, all engaged in some kind of mysterious equine standoff.

Though everywhere there are signs that the ranch was once a thriving operation, those days are now mainly locked in time, reduced to mere photos and descriptions on placards and displays installed here and there throughout the serene but still-very-much-in-operation ranch.

“There were 80 horses up here at one point, and now there are five left,” says Straub. “No breeding has been done here since 1999, and there’s no real plan to do any more. So when these horses are gone, that’s kind of the end of it. That’s the word I’ve been given, anyway. The ranch will continue to operate as long as the horses are here, and after that, this will cease being a working ranch. It’s kind of sad, but that’s the way it is.”

The Morgan Horse Ranch was established decades ago as a location for the breeding and training of Morgan work and trail horses, once the official favorite equine among national park rangers, who used them for patrolling and search-and-rescue missions. Over the years, horses born at the Point Reyes ranch have been deployed to dozens of parks throughout the western region, including in Hawaii. Today, with a few

exceptions, horses in the parks have been replaced by motorized vehicles, though at Point Reyes the Morgans are still regularly taken out for patrols.

“Morgans are a great breed,” Straub says, leaning back at his desk inside a miniature office overlooking the stables. “They are very smart and very sturdy. Morgans have a compact frame, built for pulling and going long distances. They’re also very sure-footed, so they make a great trail horse. They have big feet for their small bodies, a thick neck and broad shoulders.

“Morgans have been used throughout history as a work horse, plowing fields and pulling carts,” Straub adds, “and they’ve even been used as message delivery horses. They’ve competed in endurance races, cart races, hauling competitions. Morgans are one tough breed of horse.”

The Morgan horse was named for Justin Morgan, a New England farmer and music teacher who, in the 1700s, was given a stallion named Figure. From him, Morgan bred a line of robust working horses, one of the earliest new breeds established in the United States. Among their many qualities, they are fairly long-lived horses, too. When Straub first came to the ranch, there were eight horses, three of them more than 30 years old. The youngest two were 12.

“They’re 16 now,” Straub says, “and then we have one that’s about to turn 21—that’s Honcho, our rock star horse—and we’ve got a 24-year-old and a 25-year-old. The others are gone.”

Among the five remaining Morgans, two of them—Honcho the rock star and Elvis, one of the youngsters—recently had a rare excursion away from the ranch, appearing in the Tournament of Roses Parade, in Pasadena. The horses rode in the parade to mark the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. In front of 700,000 onlookers—and another 70 million watching on television—Straub rode Honcho, while Jon Jarvis, the current director of the National Park Service, rode Elvis.

“That was quite an adventure,” acknowledges Straub. “It was the centennial of the National Park Service. It was New Year’s Day. It was the Rose Parade, the second largest parade in the country. And it was the first time the National Park Service was involved in the Rose Parade.

“The horses both did great,” he says, proudly. “That was definitely a whole lot more excitement than they’re used to getting up here at the ranch.”

“The ranch is one part of the broader landscape of the park as a whole, and as such, it plays a significant role in the overall ranching history of the park,” says Doug Hee, an interpretive ranger at the park, and the person in charge of wrangling volunteers for the hundreds of available positions, including the horse ranch.

“There aren’t any cows up there anymore,” he says, “but ranching has been a part of this area since the Europeans arrived. There’s a definite significance in that, and in the ranch itself as a former training ground for the horses that patrolled the national parks in the West. Now, that function really isn’t needed anymore, because the parks that have horses can breed them themselves.”

Working alongside Straub—the ranch’s only paid employee—the volunteers Hee recruits continue to be an important part of the daily operation of the Morgan Horse Ranch.

“The volunteers do a lot of the hands-on work with the horses, the husbandry, the care and feeding, all of that,” says Hee, who admits that the ranch gets fewer applications than some of the more conspicuous areas of the park. “We’re not exactly getting flooded with people who want to come out to the ranch,” he acknowledges. “But that’s OK. There’s a good crew up there already, and they know what they’re doing. But we’re still always looking for new people to come and help out.”

Occasionally, he reports, new volunteers arrive expecting to spend their time out on the trail riding horses.

“But this volunteer position is not about that,” Hee says. “It’s fun, but it’s also hard work. There’s a lot of mucking out stalls, maintaining equipment, repairing fences, things like that. It’s all part of caring for these animals.”

That said, it’s an attractive notion, to the right kind of person, just to be able to spend time around the Morgans in any capacity. For those with a bit of spare time on their hands, it’s motivation enough just to

spend time in such a historic space, an active part of a remarkable North Bay tradition. Of course, as Hee adds, in addition to being comfortable around horses, it doesn’t hurt being comfortable with people as well.

“The volunteers up there do sometimes engage with visitors,” he explains. “They aren’t exactly docents, but they do perform an interpretive function by answering questions from anyone wandering around, telling them about the ranch, talking about the history of the place, and about the horses themselves.“

Straub estimates that, at present, the ranch has about 26 volunteers in total, but only a dozen of them are “regulars”—trained participants with specific routines and consistent weekly schedules. The majority are retired folks with spare time, or “slightly younger volunteers” who enjoy being around horses.

“Most of the ‘younger’ ones are in their 40s and 50s,” he adds, laughing. “I’m pretty much the youngest person out here.”

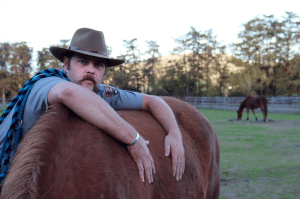

Straub came to the ranch three-and-a-half years ago, thinking he was signing on to a new job, but ending up with much more than he’d anticipated—in the best possible way.

“I don’t want to over-speak, but I guess you could say that being out here has more or less saved my life,” he says. “This job was exactly what I needed at exactly the right moment.”

After serving in the Marine Corps for four years, Straub returned to the U.S. and did construction for a while before setting his sights on law enforcement. Eventually, he attended the Ranger Academy at Santa Rosa Junior College, studying to become a national park ranger and law enforcement officer.

“At school, I met a bunch of the law enforcement guys from out here,” he says, adding that several Point Reyes rangers are instructors at the academy. After the retirement of Harold Geritz, who’d managed the ranch for many years, the position became available. Straub’s primary hands-on experience with horses was with the rodeo, working with quarter horses and Arabs, but he applied for the job anyway.

With Straub’s background with animals and horses, and his ability to do construction work, he was the perfect candidate, since a lot of ranch work is maintenance, fixing things that get broken. On a ranch, things get broken all of the time, requiring capable people to do the repairing. It was fortunate for Straub that, with the relative calm and beauty of the Point Reyes Morgan Horse Ranch, the place has a certain way of fixing people right back.

“When I got here, I was dealing with some PTSD stuff, from when I was overseas with the Marine Corps,” he says. “Coming out here was a godsend for me. It was fantastic. For people with PTSD, being out in nature is one of the best things for you, and then when you add horses to it, it’s perfect.

“Horses are extremely intuitive,” he continues. “They know when something’s up with you, internally,

probably even before you know it. The horses have totally been a healing entity, for me. Being around horses, you have to earn their trust, and the building of trust is the building of friendship, and that can be a very healing thing when you’re struggling with a lot of complicated emotions.”

Straub is one of several veterans featured in the documentary Thank You For Your Service, which recently debuted at the New York Film Festival in November, and then at West Point in early December.

“Through participating in that movie,” he says, “I eventually met some people who do ‘equine therapy’ with people with PTSD. That’s been just great. There’s no way around it; horses are just a great way for people to work through the things they need to work through.”

That leads us back, literally, to the ranch, and its uncertain future.

“It’s ultimately just the money,” Straub says, guiding a short tour across the facility and out to where the horses are waiting, watching him move toward them with interest and expectation. “That’s definitely the largest contributing factor affecting the future longevity of the ranch. It’s all about the funding. Between my salary, the cost of feed and maintenance, and all of that, it just takes a certain amount of money to keep this place operational as a horse ranch.”

Apparently, the National Park Service has decided that the money would be better spent in other ways. So unless something changes, or an outside donor drops a significant pile of cash in the near future, Point Reyes’ Morgan Horse Ranch will cease operation once the last horse dies. This is part of the reason that the ranch has stopped breeding horses, as the birth of a new colt would commit the ranch to another 30-plus years of care and feeding.

At present, the males at the ranch are all gelded, and though the female is technically breedable, she’s small, even for a Morgan, and she’s not exactly young, so her breeding days are limited.

“If we were to breed her, because of her size, we’d need to bring in a much larger stud,” Straub says, “so we could end up with a larger animal.

“Hopefully not her temperament,” he smiles. “She’s actually got a fine temperament, but she tends to be a lot more stubborn than the other horses. So if this ranch were ever to get back into breeding Morgans, we would need a breeding stock refill. And there’s no way around it; breeding programs are very time- and labor-intensive, and are very expensive. If you have your own stud, that’s a huge plus, and getting a good stud with a pure bloodline, that can be a bit of a challenge.”

The big challenge, ultimately, would be finding the money for a project so large, and it’s not as simple as just having a generous patron write a large check. As a federal agency, the ranch is not allowed to solicit for funding, so the ranch’s partner in the park, the Point Reyes National Seashore Association—which is allowed to do fundraising for the park—would need to accept the money on the ranch’s behalf.

Even then, it would need to be a significant donation if the ranch were ever to begin breeding again. Morgans live an average of 30 years, and with operating costs in the range of $120,000 to $200,000 annually—with that number likely to rise in the future—it would take a small fortune to assure that any newborn horses would live at Point Reyes for their full lifetime.

“Some of the volunteers here have made small donations to the ranch, through PRNSA,” he says. “They’ve basically written a check to PRNSA, designating the money for the Morgan Horse Ranch program. We’ve used that money to get some new equipment for the horses, some new tack and things like that. We’ve also used some of that money, when we have it, for sedation and euthanasia when we’ve had to put an old horse down.”

The sun is now fully out, and the birds have begun singing in the trees, luring out the black cat, who gazes upward for a few moments before ducking under the fence and moving out to see what the horses are up to.

“It’s such a special place, in so many ways,” Straub says. “It’s hard to imagine the day when there are no more horses here, but that day is likely going to come, unless something significant happens.”

He stops in front of a large sign, a display describing the history of the ranch, and the training practices once used to prepare the Morgans for the hard work of being a Park Service ranger horse.

“Of course, if that does happen,” says Straub, “the ranch will still be here, and people will probably still wander up here from time to time to look at the exhibits—but there will be no live horses. It will pretty much just be a museum.”

Learn more about the Morgan Horse Ranch at ptreyes.org/activities/morgan-horse-ranch.