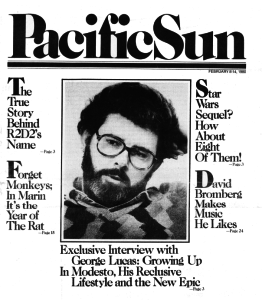

Editor’s note: With the new ‘Star Wars’ film, ‘The Force Awakens’ hitting theaters this week, we thought it might be fun to revisit an old piece, published in the Feb. 8-14, 1980 issue of the Pacific Sun. At the time, writer Joanne Williams, who continues to contribute to the paper today, scored an exclusive interview with Marin’s reclusive George Lucas. Here, we print some excerpts that we hope you’ll enjoy.

By Joanne Williams

George Lucas’s carefully calculated gamble to put a popular space fantasy on the screen has paid off beyond his wildest reckonings. Lucas and the new generation of filmmakers like him have become the Force, Hollywood’s influential extraterrestials who move about freely, Filmland as close as the cameras in their hands, principals in a universe nourished by Kodak’s silver celluloid.

Lucas has drawn the curtain on interviews since the phenomenal success of Star Wars and its four Oscars brought all the marginal people pounding on his studio doors asking for money, trying to sell him scripts, making threats. Becoming well-known was such a strain that Lucas withdrew to his editing studio in San Anselmo, wouldn’t answer the bell. The standard reply to an interview request was no. [“The last thing we want,” he says, later in the interview, “is people driving up and down the road saying, ‘They made Star Wars there.’”]

But the Sun kept asking, finally persuading him to forego the hermit image and answer a few questions. So one day last week when the thermometer crept down to 35, Lucas met the press. He was wearing a green argyle sweater and green cord pants. He’s a dark-haired man about 5 feet 6 inches with a beard beginning to touch gray. Thirty-six and beyond millionaire, he still comes off as a hellraising kid from Modesto who almost killed himself hotrodding. American Graffiti was about George Lucas.

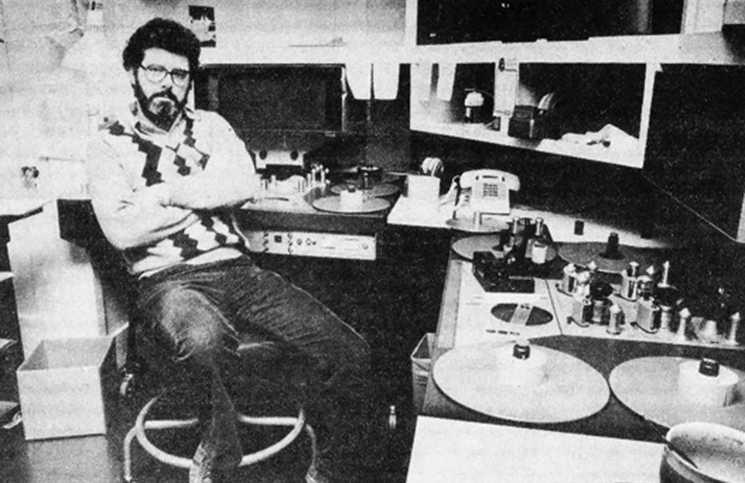

Lucas spends much of his time in the Lucasfilm editing studios, a two-story converted apartment that his wife Marcia decorated in white and buff with a dark green carpet. On the ground floor is the sound mixing studio, a small film room and a sound effects library. Upstairs are small editing rooms dominated by a clock the size of a coffee table, a fireplace with a blazing log to ward off the winter chill, a television set above it, a Betamax in the corner and several houseplants. In the bathroom hangs a white towel imprinted with everybody’s favorite, R2-D2.

Why does he keep working? Because he wants the freedom to make what he calls “my little movies,” abstract, experimental films that will “show emotion.”

Star Wars was one of the biggest box office successes of all times with a gross of $400 million. What was its genesis?

Star Wars is really three trilogies, nine films. I wrote it as one long 18-hour movie in two-hour increments. When it’s all done it will be one of the most expensive films ever made. There was no way to do it all at once; you have to do it one at a time and each time we learn a bit more technically. It won’t be finished for probably another 20 years. The next film in the trilogy, which I’m writing the screenplay on right now, will be out in 1983. I can’t give out the title now because it isn’t trademarked yet.

Did you start in the middle for artistic reasons?

Artistic and practical. I couldn’t start with the first and walk through it chronologically because the first trilogy is more plot oriented, more soap-opera-1sh than Luke’s story. The problem is like a play, the first act is essentially exposition and you’ve got to explain everything. That’s usually pretty boring so I wanted to avoid that and get into the meat of the matter, get everybody interested.

To many people, R2-D2 was the star of the show. Is he a character you made up?

The truth of the story is, when we were mixing soundtracks from American Graffiti, sound editor Walter Murch, who works with us and lives here in Marin, and I were working at three o’clock in the morning mixing a movie—we wanted to fix something in one of the tracks. You have about 15 sound tracks a film and about three or four dialogue tracks. There are 21 reels to a movie. A reel is like a thousand feet of film; that’s one spool. So Walter asked me to go over to the rack to get R2D2, that’s Reel 2, Dialog 2, and I said, “I like that, that’s a great name.” I wrote down in my little book, “Great name.” When I was developing the character of the little robot I developed it around that name.

Do you believe that your films contribute to a better world by having characters like Luke and Ben Kenobi with super-hero powers?

Star Wars was done with that in mind. As a student of anthropology I feel strongly about the role myths and fairy tales play in setting up young people for the way they’re supposed to handle themselves in society. It’s the kind of thing [psychiatrist] Bruno Bettleheim talks about, the importance of childhood. I realized before I did Star Wars that there was no contemporary fairy tale and that the number of parents who sit down and tell their children fairy tales is dwindling.

As families begin to break up, kids are left more to the television and they don’t hear bedtime stories. As a result, people are learning their mythology from TV, which makes them very confused because it has no point of view, no sense of morality. It’s a very amoral thing and as a result, unless a child has a very strong family

life or is involved with the church there’s no anchor to hold on to. So when I developed Star Wars I did it as a contemporary fairy tale. I think that’s one of the reasons it has universal appeal.

Why did you choose not to direct ‘Empire?’

I’ve sort of retired from directing. If I directed Empire then I’d have to direct the next one and the next for the rest of my life. I have never really liked directing.

Writing is what you like to do?

No, I hate writing. What I enjoy is editing. I started out as an editor. I became a director because I didn’t like directors telling me how to edit, and I became a writer because I had to write something in order to be able to direct something. So I did everything out of necessity, but what I really like is editing. I enjoy filmmaking in the pure, more abstract sense and not these giant productions.

At what point in your life did you decide you weren’t going to race cars and be a garage mechanic but a film producer?

It evolved. I was in a terrible car accident when I was 18 and spent some time in the hospital. The accident was the only thing that got me through high school. All the teachers that were going to flunk me gave me a D, so I managed to get my diploma by virtue of the fact that everybody thought I was going to be dead in three weeks anyway. But in the hospital I decided that I was going to junior college. I got interested in anthropology and psychology and stuff you didn’t get in high school. I got accepted at San Francisco State and my best friend said, “Come to USC with me, we’ll have fun down there.” I asked, “What can I do?” And he said, “They’ve got a great thing called the cinema department, films, and it’s very easy, anybody can get through it.” I said, “Great,” and I applied.

Of all the places you might have lived between here and Hollywood, why did you choose Marin?

Because when I was growing up in Modesto we came to San Francisco all the time. I wanted to live near the city and have an air link with Los Angeles. We could have chosen Santa Barbara or Monterey or the Peninsula. I knew John Korty. He lived in Mill Valley. When Marcia and I got married we came up the coast on our honeymoon and decided we liked Marin best. The further I get from the south the better I feel. I’m a northern Californian.

You really want to create a focus for the northern California film community like yourself, John Karty, Michael Ritchie and others who were written about recently in the book Movie Brats. Where does that come from?

Part of it is aesthetic, creating a good place to work. Another part is using technology to advance the film industry. The industry is really a 19th century idea. We’re in the 21st century now, practically, but film is still very crude, very 19th century. I want to update film into the 1980s. Video and sound, the more electronic mediums, are way advanced beyond film. Film is still a piece of celluloid pulled through gears and sprockets. It’s going to advance but the film studios have never been interested in investing any money. We’re talking lots of money.

What difference will it make?

On a technical level it will make it much easier to make movies. Now it’s an extremely difficult process and it will become much easier, closer to being able to write. The ideal situation is the filmmaker as a still photographer. He has one little camera and he runs around and makes a movie. Now it takes 150 people to make a movie, so you have an enormous amount of equipment and an enormous number of resources, whereas in an electronic medium it’s much easier. Eventually you’ll be able to take a machine the size of a Betamax with a little camera and make a movie. You’ll get professional quality equipment that is in the electronic mode to give us the quality we now get with film.

Have fame and wealth put a strain on your personal life? Do you like becoming well-known?

Fame is not something I wanted. It just happened. I didn’t want to be well-known. But you can’t be successful today without being well-known, and it’s unfortunate. A hundred years ago you could be successful and nobody would know who you were. There were tycoons all over the place, but now because there’s such an insatiable appetite on the media’s part … I try to keep a low profile.

Do you think you’ll ever become a more public visible person?

Around here we’re trying to walk the thin line between being reclusive and private and having a sense of community. We don’t want to start a Universal City tour out there. We are a small industry. We spend a couple million dollars a year in Marin. I look at my main community effort as my films, which I feel are a social responsibility.