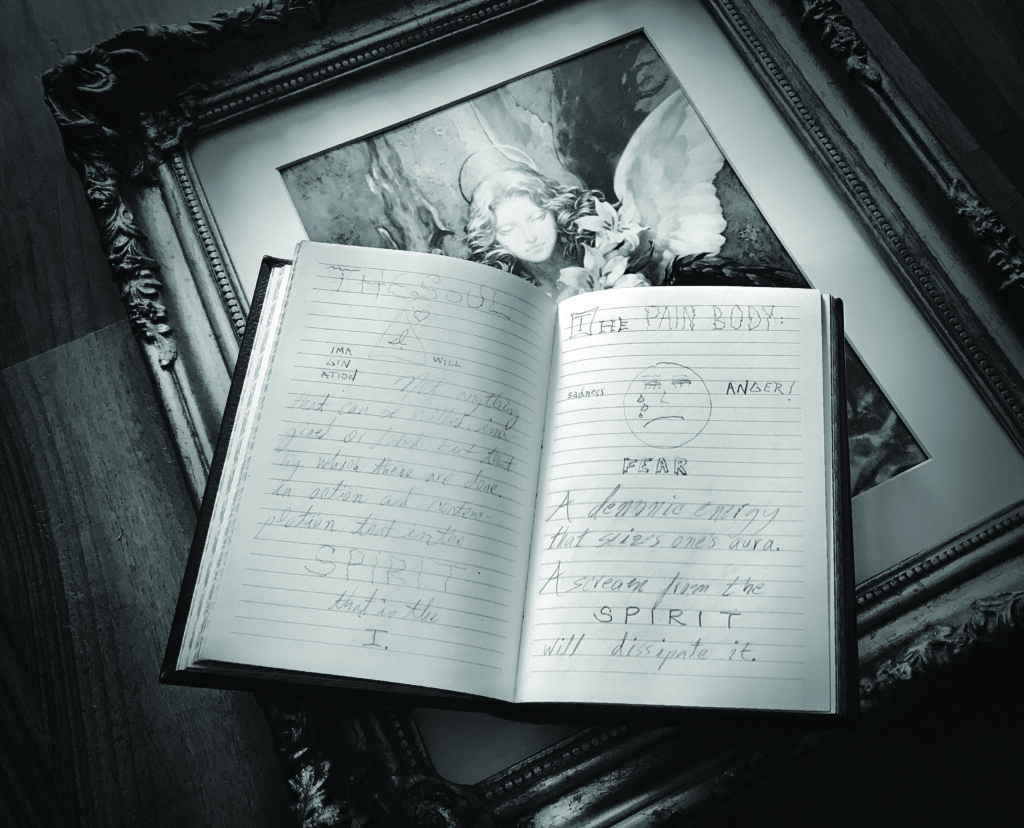

I call it my grimoire. Bound in navy leather with a silver fleur-de-lis, I didn’t know what I’d use the notebook for when I bought it. But gradually, as if by magic, it began filling itself with crude sketches and metaphysical speculations, as if I were merely the stenographer of a soul seeking to understand itself. And each time I’d arm myself with a sharp pencil and turn to a blank page, I’d get that goosebumpy feeling you get when you’re doing something you’re meant to do.

A grimoire is a book of magic, and I created mine without even realizing it. It was just an empty journal until I jokingly called it a grimoire. Four years later, it actually is one, thereby demonstrating, by way of a paradoxical causality loop, that the only possible origin of a book of magic is magic itself.

From Vegas showmen to Harry Potter, magic continues to cast its spell over a public jaded with the democratized sorcery of technology. But to the ancients, magic was no mere superstition, and instead a very real force in the world, whose chief qualifications were the focused will and evocative imagination of the practitioner. As a spiritual path, magic is not about making objects suddenly materialize, but creating states of mind that go on to manifest changes in material reality. We all exercised this power as children. Our parents told us it was called “make-believe,” and, if we were lucky, they encouraged it. With just a toy or two and a stack of sofa cushions, children can construct a mighty fortress of the imagination, capable of defending itself against the gremlins of boredom.

The troubles that plague us in adulthood are more debilitating, but there’s no reason we can’t employ the same tactic. In fact, creativity—or creative activity—might be the best defense we have against that trio of foes—fear, anger and sadness—that seek to ambush us and inject their spider-venom of anxiety and depression. New data from Gallup’s Life Evaluation Index shows that, in certain key areas, the number of people experiencing stress and worry since the pandemic is four times higher than during the Great Recession of 2008.

When you land in the pit of despondency and it feels like no light can reach you, you need to create your own, kindle an inner fire that can light your way out. Language paints the picture: you need to become enlightened, illuminated and radiant, and you can do this by creating something. Anything. A pot of soup. A fresh state of mind can be brought on by shadow boxing your inner demons, then dancing on their graves to your favorite teenage rock song. Go outside and run wind sprints until you’re out of breath, then see how you feel when you get it back. In other words, you need to throw out all your old assumptions of normalcy and start going a little bit crazy if you want to keep from really going crazy in a world that’s definitely gone crazy.

Peeling away the accumulated layers of your carefully guarded persona, fragile ego and fear of what others think, and getting down to where the raw energies lie, you’ll find a flint of magic built inside you, a gift from the greatest magician of them all. We were created to be creators, to mimic the very act that gave us life. Creation is the first and the highest of acts in the universe, and sets the example for all fruitful endeavors. Creative activity is where all art springs from, is what is really meant by the term magic, and is at the heart of the notion that we create our own reality.

* * *

With his wiseman’s beard, flowing robes and adopted title of “sar,” a Hebrew term for prince, Josephin Peladan was one of the more colorful figures in fin-de-siecle France, a milieu already overflowing with flamboyant personalities. A prolific novelist, champion of avant-garde painting and self-styled spiritual guru, Peladan encouraged artists to see themselves as magicians, to not only create works of art, but to re-mould the clay of their own selves according to an ideal.

In the world of letters, fame often comes posthumously, and Peladan’s 1892 non-fiction work “How To Become A Mage,” was recently given its first English translation. “Man has the duty and the ability to create himself a second time,” Peladan declares, writing in the masculine mode typical of his time. In fact, refusing to create ourselves is akin to quitting before the game of life is over, forfeiting our divine gift and surrendering our imagination to the machines that seek to stamp it out.

Every fleeting fancy, recurring dream, supreme ambition and burning desire inside us is a key capable of unlocking its own realization, transforming us and shaping reality in the process. “You must become incapable of pleasure that does not include imagination,” Peladan admonishes. In other words, play like children and magical things will happen. Embarking on this path means renouncing the conventions of the age and foregoing everything that has a deleterious influence. “Are you a someone or are you a social unit?” he asks the reader rhetorically. Society, he says, “is an anonymous corporation providing a life of diminished emotions.” Creating yourself anew “requires that you renounce the collective in order to be born into your personality.”

Drop an iconoclast like Peladan into the 20th century and arm him with laser beams and you’d practically have a Bond villain. In fact, save for the world domination angle, Bond villains provide inspiring examples of defiant creativity when faced with civilization and its discontents.

In 1977’s “The Spy Who Loved Me,” with Roger Moore as 007, villain Karl Stromberg has created a frog-shaped submarine that serves as his mobile lair, with a control room decorated in the high baroque, complete with tapestries that retract to reveal the creatures of the sea. In his meeting with 007, who is posing as a marine biologist, Stromberg confesses to being a recluse who has chosen to live far from society in surroundings suitable to him. When asked if he misses the world, Stromberg replies, “This is the world.” Remove the revenge-on-humanity angle and this eccentric outcast stands for the kind of artist whose medium is life itself. Stromberg has created a world that suits the needs of his soul, and isn’t that what writers do? Writers awaken characters from the bogs of their imagination and give them life, and we become co-conspirators every time we suspend our disbelief and consent to enter their imaginary worlds.

* * *

Since the millennium, many have come to imagine the universe as computer code consisting entirely of ones and zeros.

The ancients conceived the cosmic programming language as language itself, and the world’s creation myths are often based on speech or writing, with gods of language also gods of magic. Thoth (from whom we likely derive the word “thought”) was the scribe of the gods in ancient Egypt, corresponding to Mercury in Greek mythology, the planet that astrologically rules over communication. In the Norse tradition, Wotan, for whom Wednesday is named (Mercredi in French), taught man the language of the runes, used in Viking magic. The ancient text known as the Corpus Hermeticum attributes the creation of the world to the Word, and The Book of John states that “In the beginning was the Word,” further showing how our concepts of language, creation and magic are deeply entwined. But it is Kabbalah that quite literally spells out the formula for bringing anything to fruition in the form of the tetragrammaton, a fancy way of saying “a word with four letters.” The Hebrew letters Yod Heh Vau Heh stand for:

1) an active, masculine principle

2) a receptive, feminine principle

3) the union of the two

4) the fruit of this union

How does it work in practice? We start with you, whose human intelligence represents the active principle. Now find a plot of fertile soil to serve as the receptive principle, and plant seeds. Wait a few months, and you’ve got food. Now let’s apply it to literature. Say you’ve always wanted to be a writer, and have a poem, story or screenplay stashed away in your desk. You dust it off and search for a magazine, writing contest or movie studio receptive to original creations. By way of step three, you take action and submit your work, and in step four, you find they like it and are going to pay you for it. A whole new horizon has just opened up in your life. Yes, the mystery of life is really that simple, which is why it’s so easy to forget. And it’s entirely based on creative activity.

* * *

You’re not just the hapless anti-hero of your own meandering life story. You’re also the author constantly scripting pages on the fly, adapting to changing circumstances favorable and unfavorable, all the while trying to steer yourself to some vague destination you consider happiness. What it will actually look like if you get there, you’re not exactly sure, because if you’ve learned one thing, it’s to always expect the unexpected. Which is precisely how this story came about.

“In the dark night of the soul,” someone clever once said, “it’s always 3am.” Staring at the ceiling in the middle of the night recently, weighed down by the vexations of everyday life, a voice inside told me to go out and confront the darkness, to work through the black thoughts by walking through the moonless night. And as I strolled through the stillness of the neighborhood, sure enough, a little bulb of an idea, hardly bigger than a Christmas-tree light, began to shine on my consciousness.

By the time I came back through the front door, a gestalt shift had occurred. Suddenly everything in my worry-filled home struck me as the result of a conscious creative choice, from the pictures on the wall and piles of books to the thrift-store furniture I’d painted and transformed from shabby to chic. And so a restless night of brooding over matters beyond my control revealed just how much actually was under my control.

We’re always engaged in creative activity; we simply forget it and fail to summon our magic in the trying moments when we need it the most. But this perfect power, if we can understand it and learn to bend it to our will, is a force impervious to all anger, fear and sadness, coming from a higher, purer realm that knows not those tempting demons of negativity.

I opened my grimoire and jotted down my thoughts, realizing that these little insights on the power of creativity might make for an interesting story about a fretful night that finally ended with the rising of the sun, as once again the forces of light and inspiration won victory over darkness.