by David Templeton

“Depression,” says comedian-writer Johnny Steele. “I guess I’ve always known that depression was bad, that it was a disease, that some of my friends even suffered from it. But to tell you the truth, until six months ago, depression was just something I never took very seriously.”

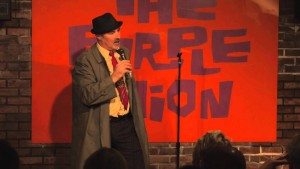

It is a testament to how seriously he takes the disease of depression today that Steele, a master of language, punch lines and witty conversation, doesn’t seem to realize that he just made a kind of a joke. Nowadays, Steele—a subject of the locally filmed documentary 3 Still Standing, about survivors of the 1970s San Francisco comedy boom—has become a kind of accidental spokesperson for taking depression very, very seriously.

The thing that opened Steele’s eyes—the event he refers to that happened six months ago—was, of course, the death of Robin Williams. On Aug. 11, 2014, after years of battling depression and other ailments, Williams, arguably one of the world’s most beloved and respected actor-comedians, took his own life at his home in Tiburon. Williams’ suicide shocked and stunned friends and fans around the world, and the additional reports of the entertainer’s mental and physical struggles just added additional pain to an already unspeakable tragedy.

For his many friends, who include Steele, the next few days were nightmarish. Television news showed tasteless shots of Williams’ house surrounded by police cars until enough public outcry shut down the cameras. In the papers, as well as on radio and television, the question was repeated over and over: How does someone who’d accomplished so much, who’d given so much laughter to the world, and was loved so deeply and widely in return, reach a point where death seems like the only choice? The tone of the media conversation ranged from sympathetic to outraged, with some conservative pundits accusing Williams of cowardice for giving up when so much had been given to him. Some of his closer associates went on the air to stumble foggily through bereft and agonizing tributes to their fallen friend and colleague.

Some preferred to keep their feelings to themselves.

“In the 24 hours after Robin’s passing I thought I’d never be able to speak about it,” says Steele, who lives in Berkeley, but for eight years was a frequent cycling companion of Williams, having gone for a long ride through Marin just over a week before the news broke about the tragedy. “Again, I don’t want to act as if I was Robin’s best friend or anything,” Steele says, a rare pause of discomfort audible in his speech. “I’d known him for years, but we started palling around seven or eight years ago, riding bikes together, and we did that pretty frequently when he was in the area. But, I’d become a bit closer to him toward the end, and I did go riding with him a lot. And so, when he passed, everybody called me and said, ‘Hey, you rode bikes with him. Let’s get you on my TV show, or my radio show, and let you talk about Robin.’” Steele admits that, for a couple of days, he didn’t want to do that.

“First of all, I was very sad, and was composing my thoughts, and I couldn’t believe it was even happening,” he allows. “And the other thing was—I was just really sensitive to the possibility that anything I said would look like I was capitalizing on this grief everyone was feeling. People do that, when a celebrity suffers a tragedy, and to me it often seems like a ghoulish, ugly thing to do.”

Steele, looking for his own answers, got out a notepad and started writing down facts and figures about the disease of depression. It was, he admits, a way to channel his own tumultuous mix of grief, guilt and anger into a form that perhaps would reveal something useful. What he quickly learned was that what he knew about depression was just a piece of a massive problem.

“I did some poking around, and the sheer numbers I was reading just threw me back,” he says. “I just never knew depression touched so many people. I think the figures I read were that 750,000 people, in the United States alone, attempt suicide every year. As a comic, we have to put everything into perspective, right? It helps us make sense of things. So … 750,000 people, that’s enough to fill the city of San Francisco. That’s just the people who attempt suicide. It’s not the people who suffer from depression, which is even huger, and I don’t remember the numbers of people who are successful at their suicide attempts, but it’s something in the tens of thousands.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were just over 41,000 successful suicides in the U.S. in 2013. No figures for 2014 have been released. The National Institute of Mental Health reports that episodes of depression, an illness estimated to affect one out of every 10 Americans, is easily the most common form of mental illness in the country. The number of clinical diagnoses of depression increases by 20 percent each year in the U.S., and still, less than 20 percent of those who have symptoms of clinical depression are receiving any form of treatment.

The primary reason people choose to suffer depression in silence: shame.

“The only shame is that we’re not doing more to battle this horrible thing that affects so many people,” Steele says. “Here’s some more perspective. We were attacked on Sept. 11, 14 years ago, 3,000 people died when the Twin Towers fell, and in response we launched two wars that went on for 10 years, killed hundreds of thousands of people, and to do it we spent two or three trillion dollars. We did all of that because of 3,000 people.

“Well, over 10 times that many people die of suicide and depression every single year, just inside the United States,” he continues. “I know we’re spending some money on it, but I don’t think we’re spending trillions of dollars. I know there aren’t parades in the street supporting the psychiatrists and counselors and suicide prevention hotline workers, people who are trying to stop this deadly, terrible thing. I know there are wars on terrorism, and wars on drugs. When are we going to start the war on depression?”

It was, in part, his gut reaction to such statistics, and partly a response to some of the more negative opinions being expressed in print and on FOX news, that Steele, a few days after Williams’ death, suddenly agreed to do a few select interviews.

“I decided to do a local TV station news show,” he says, explaining the decision that put a series of unexpected events into motion. “I told them I wanted to talk about two things. First, I wanted to talk about how Robin inspired me—what a great guy he was. Second, I felt like I needed to talk about what a monster this kind of depression must be, because if depression took a guy like Robin Williams, then, hey, nobody is safe. I wanted to say, ‘Don’t blame Robin. Robin was attacked by a demon, a demon called depression, and for reasons we are still trying to understand, the demon won.’”

Steele taped the interview with the local ABC affiliate’s nightly news program, and despite Steele’s intention of keeping himself from showing any emotion that might be sensationalized, in the last minute or so of the interview, he found himself choking up. It was when Steele was asked to speculate on what Robin Williams’ legacy would be. Steele said a few words about Williams’ energy and enthusiasm for performing live.

“A lot of comics aren’t all that thrilled at the idea of going on stage,” remarks Steele. “Whenever I think I’m phoning it in, or when a bit isn’t going well, or whenever I’m feeling like there’s something else I’d rather be doing, I think of Robin Williams, and I suddenly get this explosion of energy. When Robin was on stage, he was playful. He was excited. He loved what he was doing.”

In the final seconds of the interview, Steele admits to being reluctant to talk about what Williams’ legacy will be. With a mention of having only just begun to learn about depression, he eventually puts together an answer.

“I hope that the death of this incredible, kind, wonderful, brilliant humanitarian brings this nation closer to taking a serious look at who these people are walking the streets and screaming at parking meters—why are people killing themselves? It’s a terrible thing, man, and I wish his legacy would be something else, but part of his legacy is going to be that, and that may be greater, and save more lives, than any movie or comedy show we ever did.”

On tape, it’s an extremely powerful moment.

“The cameraman started crying,” Steele says, “and it made me lose it a little. I got more emotional than I was trying to do on camera. So I broke down a bit. And I felt really bad about it. It just seemed like the kind of thing that took the focus away from Robin and put it on me, and I hated that. I hated it.”

Steele actually attempted to stop that part of the interview from appearing on the news, but it not only ended up airing, the station posted the entire interview on its website.

“I hadn’t agreed to that, and I was a little pissed off,” Steele says. “I just wanted to give a little insight into the guy, and now I was afraid it had backfired. I was really angry, and I wrote to them, and said I wished they’d take it down, but they didn’t—and then the letters started coming in.”

It was a turning point that quickly changed everything.

“In the mail, on Facebook, in notes to me personally on Twitter, I got these emails and letters and notes,” he says. “Some people found me through my website, people in the Bay Area, people in Boston and New York, people in Europe. There must have been a hundred messages within the next few days.

“The ones that were most moving were the people who said, ‘I have battled this disease for years, and I’ve lied to everyone about it. I’ve hidden it. I go to a psychiatrist, but I’ve never wanted anyone to know. I didn’t want my family to know, because I don’t want them to think I’m a weakling. But I’m coming out now.

Because of what you said about Robin Williams. Because you said that depression must be a tremendously powerful demon, and that if it takes Robin, who else is safe? I see now that depression isn’t my fault. So I’m going to stop lying about it and let my friends and family help me any way they can.’”

The letters kept coming.

“One letter said, ‘My son killed himself, and I’ve been thinking it was because of something I did wrong, or didn’t do right. Over and over I’ve been asking myself, “What did I do? What didn’t I do that I should have?” And I realize now that I could have done nothing. I realize now that what happened to Robin is what happened to my son. And if Robin couldn’t get around it, or out from under it, then no wonder my son couldn’t get out from under it either. I have to stop blaming him, or blaming myself.’

“There were all these beautiful, beautiful letters I got,” Steele goes on. “They were so inspirational. And some people said, ‘Thank you, thanks for saying that, because it helped me more than you can know.’ And believe it or not, six months now after Robin’s passing, I’m still returning these emails. I’m still having people come up to me after a comedy show, or a screening of the film at a film festival, and they tell me these stories. They tell me that Robin’s death gave them a way to see this disease in a different light. People have come up to me and said, ‘I’m not embarrassed anymore that I have clinical depression.’ And they cry, and they give me a hug, and I try to do what Robin would have done.”

Steele listens to the stories.

And sometimes, he even hugs them back.

“I have to admit that before Robin passed—and this is another thing that has sideswiped me to admit—my eyes were closed to what depression is. I’m sorry it took a friend of mine dying to open them. I think I probably had a very different perspective when Kurt Cobain died. I didn’t know him, but I remember having a more thuggish response to his death. I liked his music quite a bit, but I think I probably said, ‘Oh, he was depressed? Boo hoo! What a pantywaist. Why didn’t he just pull himself up? He’s got millions of dollars and everything to live for! What kind of an idiot throws all of that away just because they’re sad?’

“I probably said exactly that,” he says. “Being close to a guy makes you see things differently.”

Now half a year after Williams’ death, the sting is still strong with many people, but the nature of that sting is changing. Steele has noticed it in many little ways, including the response audiences give during one particular moment in the aforementioned film 3 Still Standing. While the specific focus of the documentary is Steele, and fellow comics Will Durst and Larry “Bubbles” Brown, several other notable Bay Area comics—including Robin Williams, who taped his interview early last year—appear onscreen to talk about the San Francisco comedy boom and bust in the ’80s.

“In the summer, not long after Robin passed, we showed a trailer of the film at the Bernal Heights Film Festival in San Francisco,” recalls Steele. “And the audience was laughing at the clips, laughing at the little snippets of stand-up, and the various people saying various things about comedy—and then when Robin’s face appeared, they just all went … ooooh. It was like the clichèd punch-in-the-gut. The air went out of the room, and you could feel the emotion in the air.

“In recent screenings of the complete film, though, it’s changed a little,” he says. “Just in the last couple of months, when we screen the movie, and Robin shows up, people sometimes applaud. They clap, and sometimes they cheer. Maybe we’ve gone through the initial grief period, and now we’re into an acceptance period of some kind, where people are at least able to say, ‘Hey! There he is. We miss him. Let’s let him know.’

“It doesn’t happen often, but it does happen.”

Now, with the Oscars on the horizon, and the inevitable moment when millions of people around the planet will watch the annual In Memorium segment of the broadcast, during which Robin Williams’ face and voice will join all of the other entertainers who’ve passed away in the last 12 months, it is possible that the enormous worldwide grief for Williams will see a fresh spike.

Steele, for one, won’t be watching. He’ll be performing at a benefit at Cobb’s Comedy Club in San Francisco.

A tribute to Robin Williams, the event, which also features Rick Overton, Bobby Slayton, Dana Gould and others, will raise money for one of Williams’ favorite causes—helping the stray dogs of San Francisco.

Asked today if, after half a year, the commitment to talk frankly about depression and suicide is still as strong, Steele is uncharacteristically silent for several seconds.

“I think I’m still processing Robin’s death, to be honest,” he says. “I still can’t wrap my brain around it. Did it change my life? Yes! Did it make me want to take on the world and fight the fight against depression, and get people to do something? Yes! Will I still feel this strongly about it in a year? I can’t tell you that. But for now, when the opportunity comes up to talk about depression during a Q&A, or to talk to someone after a show who’s hurting, or to call a friend who I know is struggling with depression and say, ‘Promise me that what happened to Robin won’t happen to you without a fight. Promise me you’ll call me and let me come over and talk,’ well then, right now, yeah, I will do everything I can, and I assume there are a lot of other people doing the same thing.”

Whatever legacy will come from the tragedy of Williams’ death, it will happen through people like those regular people who either knew the embattled comic or only watched him from afar, people now offering a more informed answer to the question: Why did Robin Williams kill himself?

“Why did Robin kill himself? He didn’t. That’s how I see it now,” Steele says in his own answer. “I don’t think Robin sat down and voluntarily said, ‘Hey, here’s what I’m gonna do. I’m going to get seriously depressed and when it’s as bad as I can take it I’m going to end it all.’ Depression lies to you. It makes you believe something that isn’t true. It makes you think you’ll be better off, and the people you love will be better off, and it’s not true.

“I wish we could talk to the depression, to reach through the fog of it and tell people who are considering suicide, ‘Hey! I’m sorry, man. I know you’ve got some horrible pain, and you’re suffering from it, and I wish we could figure out how to stop that—but know this. No one will be happy if you go away. You might be in the very bottom of this pit, and hopefully you’ll find a way out again, and I know you’ve been in it off and on for years, and you’re suffering, and you’ve been suffering real bad for months in a row lately.

“But everybody wants you to succeed. Everybody wants to help you. And, by the way, it’s not your fault if you have depression, and it’s not your fault if you listen to the lies. But don’t—please don’t listen to the lies. ’Cause that’s all they are.”

Steele stops again.

Whether he was just travelling back in time and speaking to Williams, or into the future, to all of the millions of people who will someday battle the illness that claimed his friend, it doesn’t matter. Either way, the only solution is to keep fighting.

“I know,” Steele says, “there has to be a way to stop this fucked-up disease. There has to be. And I just hope we find it soon.”

Contact the writer at ta*****@*******nk.net.

Thank you for this article. I still feel the loss, and I didn’t know him.

Hi David,

Thanks for the article about Johnny Steele.

I’m a comedian/actor friend of Johnny’s. I’m going to call him and say hello.

But I can also talk to you about it. I have licked my problem of depression. Yes, I will go that far as to say that it’s licked. No drugs. No anti-depression medication. No religious conversions. Just good sound therapy.

Unfortunately, when I write about this online, people usually become irate, saying that I should stop bragging about it, that I should spend more time giving sympathy to victims of depression. I never intend to brag about it. I only intend to offer help. But without a back and forth dialogue, in which I can answer questions, I cannot fully explain myself.

Johnny says “there has to be a way to stop this fucked-up disease. There has to be. And I just hope we find it soon.”

There is a way. And it’s quite well known among certain mental health experts: Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT).

But…learning about it does require responding to people who frequently misunderstand the principles. And one of the big causes of depression is distorting reality. So it’s very easy for depressed people to misunderstand the principles of REBT, and falsely dismiss the methods as ineffective. But it really doesn’t require more than 10 minutes to explain the whole thing.

Anyway, feel free to give me a call if you’d like. I will be calling Johnny.

Mick Berry

415 595 3600

Thank you for posting this. Many people are still processing and mourning his loss. I was never depressed clinically, but due to a spine issue (arthritis) which causes all kinds if neurological problems and pain i can only imagine how a neurological condition was the straw that broke the camel’s back…..he was clearly suffering….