Since the late ’80s, San Rafael’s Bedrock Music and Video is very likely the place where a generation of Marinites bought their first CDs, rented their “Thursday Rental Specials” and otherwise browsed away an afternoon on the Miracle Mile before decamping to Caffé Nuvo. And now it’s closing for good.

It’s another end to an era that already ended a long time ago before entertainment companies began chanting “merrily, merrily, merrily, film is but a stream.” To those last video-rental stores that dot the nation like a fading constellation of supernovas, it’s not “Neflix and chill” so much as “Netflix and kill.”

Streaming killed the video store

Streaming has long been the obvious nail in the coffin for video stores, and what stores remain have become mausoleums for the dead medium known as the Digital Video Disc. Which is a shame for a variety of reasons. Back in the ’80s when I was an aspiring auteur—seeing is believing: rent Pill Head, my 2019 paean to arty cinema, on Amazon—repertory houses like Petaluma’s erstwhile Plaza Theater were the only way to steep in the films of French New Wave, American indies and forgotten and/or forbidden classics. When those dimmed their lights for the last time it was up to video stores to fill the void, which they did with aplomb, especially during the “Golden Age” of DVDs, when outfits like the Criterion Collection began curating art house-worthy collections of must-see flicks. These films were often accompanied by “extras,” like directors’ commentaries and “making of” documentaries, that were tantamount to master classes in the art of cinema. For some of us, video stores were film school.

Bedrock of Ages

This is not a history of the store. I wasn’t even a customer until recently, and even then it was as an admitted culture vulture taking rueful pecks at the unicorn as it lay dying. Yes, I scavenged its treasures, but out of respect for the movies, the medium and the doleful merchant behind the counter.

According to the store’s website, founder Barry Baum launched Bedrock in 1988 as a rebuttal to the big-box chain stores of the era. By the ’90s, it had reached what we might call High Fidelity status, meaning that it became a haven for discerning music consumers, a la the store featured in Nick Hornby’s novel and the Stephen Frears film of the same name.

Unfortunately, Baum died of cancer in 1996, at which point his wife, Patti Baum, took the reins of the store and expanded the offerings to include in-store events. Nine years later, Marin County non-profit Four Winds West, a transitional program for at-risk young adults, took on the store as a means of “providing vocational training and experience as a bridge to employment in the community at large.” The organization shuttered two years ago, but the store persisted—until now.

At the behest of a kind employee, I was pointed in the direction of the store’s founder, or at least one of their survivors, to get a more comprehensive history from someone who might count as a primary source, but an email went unanswered. Suffice it to say, I gleaned a few facts visiting the store on multiple occasions such as A) Everything is on sale, often with huge discounts and B) the store will likely close permanently sometime in March 2022. All in, that means Bedrock lasted approximately 34 years—a feat for any small business, let alone one transacting physical media in a digital world.

Running a video store is difficult. I did it once, as a performance-art piece with my partner, conceptual artist Kary Hess. We recreated a video store in an apartment stairwell for a single evening—Arts Editor Charlie Swanson even wrote about it.

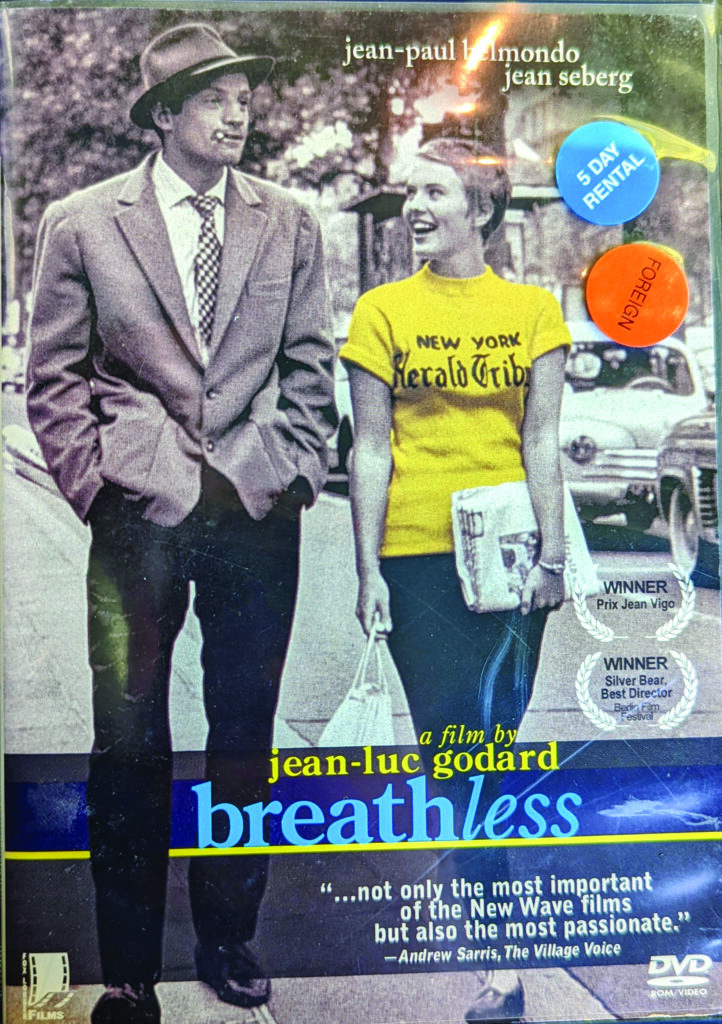

I was with Kary when I finally discovered Bedrock. We randomly visited it while trying to fill a recent Marin afternoon. Naturally, we gravitated towards the artier section of the store. There were the usual suspects—including the aforementioned French New Wave. I was acquainted with most of the auteurs through college classes that fixated on Francoise Truffaut and especially Jean-Luc Godard and their evolutionary jump from penning screeds at Cahiers Du Cinema to Jules and Jim and Breathless, respectively. Somehow, the film classes I took in the ’90s omitted Agnés Varda and her seminal works, Cleo 5 to 7 and her first film—which predates her male cohort’s efforts by six years—La Pointe Courte, which I had never seen. But there it was, nestled on the Criterion Collection rack at Bedrock.

We bought the DVD for two bucks, even though at that moment we didn’t own a DVD player. Why would we? The aughts-era promise of “convergence” happened nearly a decade ago. Now we subscribe to a half-dozen streaming services, from the obligatory Netflix and Disney+ to specialty streamers such as Shudder and an ever-rotating ensemble of week-long “Free Trials.” Yet, I bought a new DVD player via Amazon Prime which, ironically, is also where I often stream shows.

The most compelling argument for the conservation of DVDs is the fact that the versions of some films available solely via streaming are not their best versions. Case in point, Amadeus, Milos Forman’s masterpiece about the one-sided rivalry between Salieri and Mozart. The only version available to stream is the “Director’s Cut,” which, bless Forman’s dearly departed soul, is larded with useless scenes that bloat the film and cloud the narrative tension of the original theatrical release. Fortunately, that cut is available on DVD—a copy of which I seized upon at Bedrock and gladly paid two bucks to own. This isn’t the only film that didn’t leap the digital divide in its best form—in fact, some films failed to make the leap at all. Alan Rudolph’s tale of an expat American in 1920s Paris, The Moderns, for example, can’t be streamed anywhere. I now own it on disc.

Zombie media

I have a theory that media that is round and disk-shaped will always return. It’s primary shape, a circle, speaks to the cyclical nature of tastes and life in general. To alien eyes, stores like Bedrock might appear to peddle mere circles contained in squares. To weirdos like me, they are a reminder of Nietzsche’s adage, “Time is a flat circle.”

Those who don’t believe me or Friedrich might pause to consider that analog media, like vinyl records and even VHS tapes, are having a moment again. I suppose this technically makes formerly dead media “zombie media.” Digital content stored on physical media like CDs and DVDs, however, have yet to become fetish objects. One reason could be the alleged erosion of their data after a decade or so. Also, they’re too young a medium, relatively speaking, to inspire the nostalgic cache that, say, casettes tapes have recently acquired. CDs and DVDs are essentially twins and, thanks to the overly aggressive marketing efforts of AOL in the ’90s, their ubiquity made them as disposable as the very drink coasters they often became.

Also, at least with CDs, there is the sound-quality debate. Speaking of which, to anyone who ever wants to put me to sleep, just explain digital sampling rates versus unconsciously “felt” frequencies to me. None of this is relevant when it comes to DVDs, however, not least of which because the picture quality—especially for Blu Rays—is allegedly superior, or at least comparable, to streaming services.

All of this is moot to me. My TV is 4K, but my eyesight is less than “standard definition.” I can’t read the American Graffiti DVD box I just bought from Bedrock without squinting and holding it at arm’s length—and that’s with glasses on. Will that diminish my enjoyment of the movie? No. Do I know that parts of the film were shot in San Rafael, literally blocks from Bedrock Music and Video? Yes. Time is a flat circle. So are the Star Wars Blu Rays whose “extras” discs were lost a long time ago in a video store far, far away.

Interestingly, George Lucas once opined to this very newspaper that “People are learning their mythology from TV, which makes them very confused because it has no point of view, no sense of morality.”

And all these years later, I’m loading one of his myths into an antiquated technology, like Princess Leia inserting the plans to the Death Star into R2-D2, so I can watch it on my TV.