By David Templeton

“How about the Mayflower?” suggests musician Danny Sorentino. We’re standing in front of the Christopher B. Smith Rafael Film Center. “We just saw a movie about the Beatles, right? We’d be wrong not to go have a beer at a British pub now, you know?”

Well argued. We turn and head up the street toward the Mayflower Pub, with the sounds of the Beatles still ringing in our ears.

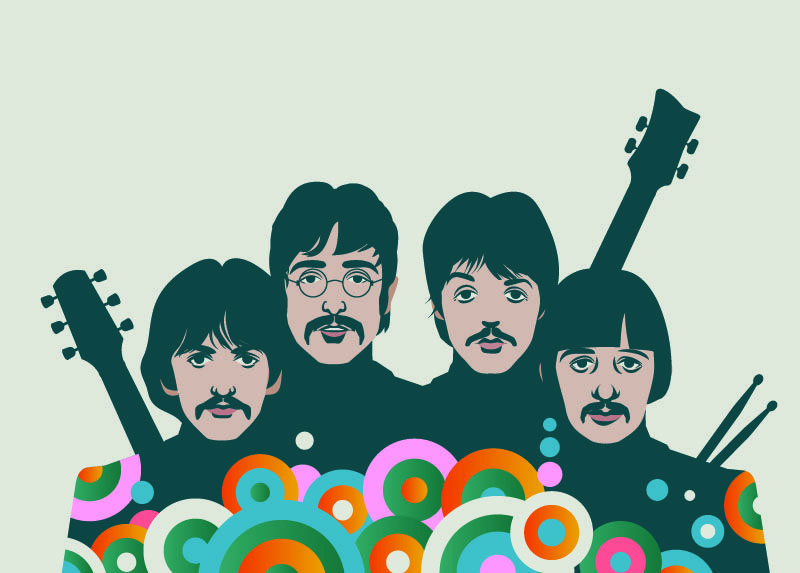

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years—now screening in an open-ended run at the Rafael—is director Ron Howard’s highly entertaining documentary about the fab four’s early years, and the factors that led to the world’s most popular band retiring from live performance in 1966. Simultaneously released online on Hulu, the remarkable documentary is accompanied—in theaters only—by a beautifully remastered 30-minute concert film of The Beatles’ iconic 1965 concert at Shea Stadium in New York City.

“I think we forget how much those guys accomplished in such a short time,” Sorentino says. “I don’t think any other band has done so much in so few years. They worked incredibly hard, that’s for darn sure.”

Working hard. That’s something Sorentino knows a lot about.

For more than 30 years—often at the helm of his hard-rocking roots band The Sorentinos—Danny Sorentino has worked days on the docks of Oakland, and played the clubs and bars of the Bay Area at night. The veteran of several European tours, he’s recorded dozens of albums. He’s opened for Bob Dylan, Peter Frampton and Hootie & the Blowfish. He’s like the Energizer Bunny of the rock ’n’ roll world.

His most recent album is Danny Sorentino sings and then doesn’t, a delightfully eccentric solo EP featuring 10 characteristically clever pop-rock-blues-country tunes, many of which put an engagingly humorous spin on the subjects of love, aging, working hard, the onset of existential disillusion and the hovering omnipresence of eventual death. It’s a rollicking, toe-tapping hoot, one you can actually dance to—when it’s not leaving a bit of a lump in your throat.

By the time we arrive at the Mayflower and order some beers—Sorentino has a Guinness—we’re deep into analyzing the Shea Stadium footage that accompanies the film.

“I love the moment where John just loses it and starts speaking in tongues, or whatever that was,” Sorentino says with a laugh. “Those guys were under so much pressure, playing to the biggest audience that had ever been assembled for a concert.”

“The crowd was screaming so loud they couldn’t hear themselves play,” I add, pulling from interviews about that concert that appeared in the documentary. “People kept breaking from the stadium and running toward the stage, only to be tackled, one after another, by security guards, before they could get to the stage.”

“You could see on their faces how freaked out they were, but they didn’t stop,” he says. “And then, when they do that final song and start looking like they’re finally enjoying themselves? I really think they were just happy they’d made it through, and not made any major raspberries.”

Sorentino’s songwriting and sound are solidly American. That said, he admits that Beatles influences run all through his music.

“On most of my records, there are at least one or two things where I was trying to do something Beatle-ish, maybe a similar chord progression, or a backward tape thing thrown in there. I’ve done all that stuff.”

“The Beatles broke up in 1971,” I point out. “That was 45 years ago. Why do you think they continue to be so popular?”

“It’s the songs. It’s no more complicated than that,” Sorentino says. “That’s the bottom line. They wrote dozens and dozens of the greatest songs ever written.”

Asked if he’s ever seen a Beatle live, he cites the George Harrison concert at the Cow Palace in 1974. “It was a great show. And 10 years ago I saw Paul McCartney, in San Jose. That was one of my top five favorite shows of my life. And I’ve seen everybody worth seeing, at one time or another.”

“I gotta ask, Danny, do you have a favorite Beatles song?”

“I do, definitely,” he says with a nod. “‘A Day in the Life,’ that’s my favorite. The John Lennon vocal alone is amazing. The subject matter is awesome, and it’s so well-written—and then, in a way, it’s just the ultimate Lennon-McCartney collaboration. So, what’s your favorite?”

“This is not the most sophisticated choice,” I acknowledge, “but my favorite might be ‘Yellow Submarine,’ because I remember singing it in the back of the car with my brothers, all of us singing at the top of our lungs. The song has strong emotional associations for me, because when I hear it, it takes me right back to that car, with none of us wearing seatbelts—because it was OK not to back then—with my mom at the wheel, smoking a cigarette and stubbing it out in the ashtray that was built into every car in the 1960s.”

“There! Right there!” Sorentino shouts, laughing. “That right there, that’s why the Beatles are still so big. It’s the connection the Beatles have to all of us, to our whole lives. Lots of bands have that, sure, but the Beatles, so much more of it.

“And for the most part,” he goes on, “our ‘Beatles memories’ are happy memories. Have you ever noticed that? Think of how fucked up the world is, and how crazy sad and scary it is today. Then imagine listening to ‘Yellow Submarine,’ and the world gets better for three minutes. That’s what these guys sacrificed for, and worked so hard for, and nearly killed themselves for.”

“Some would say they reaped huge awards for all of that sacrifice,” I mention.

“So what? So they wanted to be famous? That doesn’t erase the fact that they worked so hard and gave up so much to become the musicians they became,” Sorentino says. “This movie proves that. And now, that music belongs to us, to the whole world, the music that gets a lot of us through our lives.

“Just the fact that there is a little island of ‘Beatle joy’ that still exists in the world,” he continues. “It’s kind of a miracle, you know?”