by Steve Palopoli

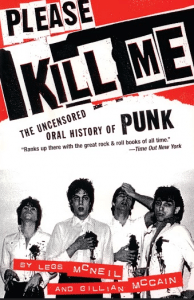

In much the same way that punk was a musical revolution, the definitive book about punk was a literary one. With its modernization of the oral history tradition—telling its 424-page story entirely in a string of quotes that form a solid, winding narrative—Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk revolutionized both the book industry and the way we think about storytelling when it was published in 1996.

Despite its gritty, grimy subject matter (or, more accurately, because of it), Please Kill Me was sublimely elegant in the way it matched form to content. Finally, here was a book about punk that reflected the actual spirit of the movement by representing its subjects’ words as directly as possible, with a minimum of filters or interference from the authors. It took nonfiction back to its primal urges.

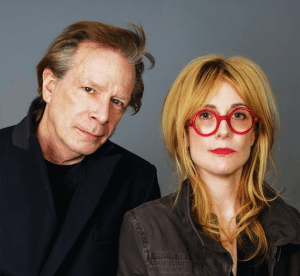

Perhaps the book’s mix of iconoclasm and literary ambition makes sense considering it was co-authored by two writers with very different backgrounds, but a surprising like-mindedness. One, Legs McNeil, is the man some credit with giving punk music its name in the first place, when he founded Punk magazine in 1975.

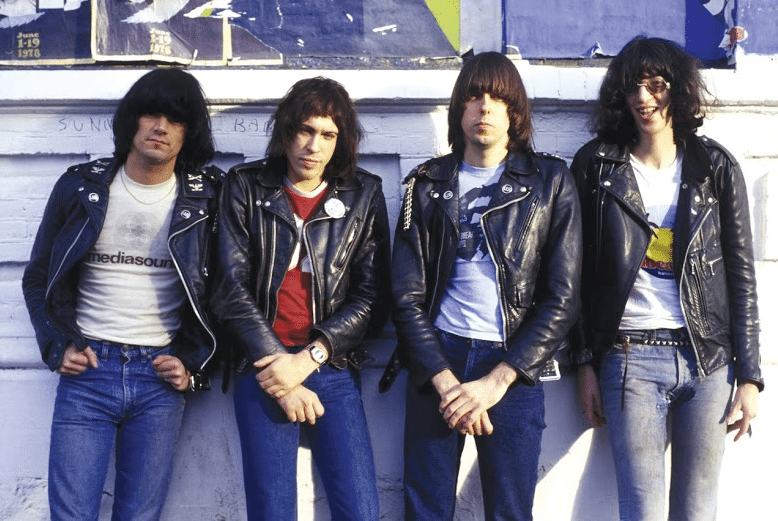

He started it with cartoonist John Holmstrom and publisher Ged Dunn, and together they provided a fledgling New York scene led by the Ramones, Patti Smith and Richard Hell (and eventually also British bands like the Sex Pistols) with a unifying concept. His co-author, Gillian McCain, was the program coordinator of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church—famed for its connections to Smith, Jim Carroll, William Burroughs and other punk poets beginning in the 1970s—from 1991 to 1995, roughly the same time that they worked on Please Kill Me.

After hundreds of interviews with everyone from icons like the late Lou Reed and Iggy Pop to lesser-known scene stealers like former “company freak” record exec Danny Fields and filmmaker Bob Gruen, the result was the bestselling book ever about punk music, which has been published in 15 languages around the world.

Now, as Grove Atlantic prepares the 20th-anniversary edition of Please Kill Me, the book sits side by side with the dozens of imitators it has spawned, everything from similarly focused music books like We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A. Punk; Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music; and Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal to general-pop-culture megahits like Live from New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live by Tom Shales and Andrew James Miller, and their follow-up Those Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN (about which a fictionalized major film adaptation was recently announced). The oral history craze has reached such a fever pitch—and, perhaps, level of absurdity—that the July issue of Vanity Fair features the “definitive oral history” of the movie Clueless.

So why isn’t Legs McNeil proud of blazing a trail for this new wave of 21st century oral histories?

“They sucked,” says McNeil by phone from L.A., where he and McCain are working on a new oral history book about the ’60s rock scene there. “I wish someone would do a good oral history. At least as good as Please Kill Me, you know?”

McCain, on the same phone call, is more diplomatic. “When I look at just the punk books that have come out as oral histories, not even oral history music books, I think there’s a hundred, literally. It’s just unbelievable,” she says. “So Legs may not be proud that we were the trailblazers, but I am.”

FIRST PERSON SINGULAR

McNeil’s stance may sound like punk posturing, but actually the pair adhered to some strict rules while doing Please Kill Me that later imitators have often ignored, usually to their detriment.

“We refuse to cheat,” says McCain, “where we’d have a piece of prose in between two people talking. ‘And then so and so went to blah blah blah.’ To me, that’s cheating.”

McNeil says the demanding structure of oral histories is what makes them so easy to screw up. With no exposition to support them, the quotes have to weave a tight narrative.

“They’re really difficult,” he says. “Oral histories are like rock and roll itself—very, very fascistic and anal. Seriously. Once you break the formula, no matter what you’ve done up till that point, the whole thing falls apart. It’s not like you can make a mistake. You know, like in memoirs there are shitty chapters where the guy goes off on his cat or his mother or something, and you go with that because it’s going to get good again. But in an oral history you can’t have that, because it’ll collapse.”

Please Kill Me established a blueprint for understanding the punk movement that has been followed by almost every book since, with the Velvet Underground as the first real protopunk band, and Lou Reed as the godfather of punk. While the Velvets were already widely accepted as punk progenitors by the ’90s (with no small amount of credit going to the 1990 cover album Heaven & Hell: A Tribute to the Velvet Underground, which kicked off the tribute record craze), the actual story of how punk evolved from band to band through New York and Detroit had never really been told.

But the book’s framing device—beginning with the Velvet Underground starting out in Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, and ending with the band’s reunion in 1992—was something that developed over time. Finding such a framework was key, since the origins of punk could be said to stretch all the way back to the beginning of rock itself; just look at how the Sex Pistols worshipped Eddie Cochran, or how the Cramps covered the Johnny Burnette Trio and the Count Five.

“It wasn’t easy, because we started interviewing people from [’60s garage band]? and the Mysterians,” says McCain. “So we weren’t sure we weren’t going to go that avenue, but it ended up we didn’t. There’s so many garage bands. And the people around the Velvet Underground were in the narrative later, so they were part of this intertwining—with Iggy, and Lou on the cover of Punk magazine. But with the garage bands, there was no interconnectedness.”

“What we did in Please Kill Me was we showed the linkage from the Velvet Underground to the Stooges,” says McNeil. “Nico moves in with Iggy, John Cale produces Iggy’s first album. We kind of mapped it all out, and every punk book has taken that formula. And no one has ever said, ‘Hey, thanks for connecting the dots!’”

“I think a lot of people give us credit,” counters McCain. “Often in the acknowledgements, they’ll say, ‘We want to thank Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain for turning us on to this format.’”

“Well,” grumbles McNeil, “maybe they should have bought us dinner.”

SCRAP MEDDLE

The dynamic between McCain and McNeil is a fascinating one.

One of McCain’s earliest memories of meeting McNeil speaks volumes about their dynamic.

“We had a mutual friend, and she said, ‘I’m going over to Legs’ to watch a movie.’ And we became friends. He lived on St. Mark’s and First [Avenue], and I was working at the Poetry Project at Second Avenue and 10th, so he’d drop by the office,” she recalls. “He’d come to readings and really drive me nuts, because during a poetry reading he’d be standing at the back, and whenever he’d move the least little bit, his leather jacket would creak. It just drove me insane. That’s how we met.”

“It was a doomed relationship,” says McNeil drily. “She does a great imitation of me coming to the Poetry Project. I’d go, ‘Let’s go out for a cigarette,’ and then I’d split. I was always embarrassing her.”

Disagreements over who and what would make it into the book could be contentious, but McCain says McNeil was able to make tough editing decisions that she couldn’t bear.

“Legs really forced me to edit,” she says. “At first I was like, ‘No, I want to put in Ed Sanders learning semiotics at grad school at NYU.’ And he was like, ‘No.’ ‘But it’s so good!’ ‘No.’”

“Gillian and I argue a lot,” says McNeil. “If Gillian really sticks to her guns, then I have to scratch my head and go, ‘Whoa, wait a minute . . . ’ I’m pretty forceful, and I have a pretty strong personality. But Gillian seems to be able to cut through the bullshit.”

For all of their differences, he’s surprised at how much they think alike, which comes out especially when they do interviews together.

“We always look at each other knowingly,” says McNeil. Also, we never use notes, which is really weird. The person stops talking, and we both come in at the same time with the same question. That happens about 85 percent of the time.”

“That’s true,” says McCain. “I think that’s something that makes people comfortable, that we don’t bring in notes. We just have conversations with them. Sometimes I have a few notes on a Post-it that I put in my pocket, and when I go to the bathroom, I look at it.”

“I always lose my scrap of paper,” McNeil says. “But since I’ve written it down, I know what it is.”

McCain credits McNeil with eliciting many of the stories that made Please Kill Me both shock and amuse. The book is full of them: Nico giving Iggy Pop his first STD. Billy Murcia of the New York Dolls choking to death in a flat in London while partygoers around him flee. Dee Dee Ramone writing “Chinese Rock” out of spite toward Richard Hell, but then giving Hell a co-writing credit for it because he wrote two lines. Malcolm McLaren on the differences between New York punk and the Sex Pistols.

toward Richard Hell, but then giving Hell a co-writing credit for it because he wrote two lines. Malcolm McLaren on the differences between New York punk and the Sex Pistols.

“I learned so much from Legs,” says McCain. “He gets on the phone with Malcolm McLaren and goes, ‘First off, I don’t want to talk about the Sex Pistols.’ And Malcolm McLaren is so fucking relieved! He asks him questions about the New York Dolls, which he was probably rarely asked about before Please Kill Me. And then gradually the Sex Pistols come up, but he’s more engaged, because he didn’t think he had to talk about it.”

“You disarm people,” admits McNeil. “You’ve got to be immediately intimate with them. Because you’re going to ask them everything. You’re going to have to ask them who they’re sleeping with, what drugs they were taking, what they were thinking, what their emotional state was at the time.”

Still, McNeil says he has yet to interview someone who was reluctant to talk.

“I think for a lot of people it’s almost like therapy. They’re really into telling their story,” he says. “It’s kind of fascinating.”

TOO TOUGH TO SELL

McNeil’s experimentation with the unfiltered style of Please Kill Me can be traced, to some extent, back to his time with Punk magazine.

“Kind of with the Q&A interviews, which were hysterically funny,” he says. “Holmstrom would do things like in the first Lou Reed interview, Lou was talking about his favorite cartoonists, and John drew him in the different styles, like Wally Wood. It was very cool. We did things like when I interviewed Richard Hell at Max’s and I passed out—and Richard kept talking. Stuff like that. That was fun, you know?”

Both McNeil and McCain were inspired by Edie: American Girl, the 1982 oral history of Edie Sedgwick by Jean Stein and George Plimpton. Though a bestseller and critically acclaimed for the groundbreaking exposition-free style that anticipated Please Kill Me, it failed to have the same cultural impact. McNeil, however, saw its potential.

“He started doing a book with Dee Dee [Ramone],” says McCain. “Dee Dee asked him to write his autobiography with him. Legs had the idea, because he loved Edie, to do it as an oral history. So he was getting Danny [Fields’] interviews transcribed, and all these people, and I said to him, ‘This story is so much bigger than Dee Dee. He’s a seminal character, but it’s just such a huge story.’ Then Dee Dee got kind of hard to get along with, and when they parted ways, Legs was like, ‘Do you want to do this with me?’ So that’s how it started.”

Considering that Please Kill Me would go on to have a huge impact on the book industry, it’s ironic that publishers showed no interest in the project at first. Despite 1991 being “the year punk broke,” as one documentary title put it, with the success of Nirvana’s Nevermind and pop-punk bands like Green Day and the Offspring storming the radio in 1994, a book about punk was still a tough sell back then. And it certainly didn’t help that it was an oral history, a literary genre associated with Studs Terkel books about old-timey things like the Great Depression and World War II.

“We knew we wouldn’t be able to sell it on just a proposal and a chapter, because people wouldn’t get it. Not only the subject matter, but also the oral history format. So we had written the whole book before we tried to sell it,” says McCain.

The exhausting interview schedule had some out-there moments, like the interview with former Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton, which McNeil counts among his favorites.

“We did like 10 hours in one sitting. Drinking milk and vodka or some weird thing,” says McNeil. “I was just listening to him, and he’s talking to his cats through the whole thing. ‘Leave her alone, Patches!’”

The great white whale for the two of them was Iggy Pop. “We purposefully wanted to leave him for last, because we wanted to be able to ask really informed questions,” says McCain.

Iggy ended up being McCain’s favorite interview that she did with McNeil.

“I think we ask questions in a certain way that maybe makes people think about things in a different way, or reminds them of certain things. That was our goal, to get stories other people hadn’t. But when you ask a question [to Iggy Pop] like, ‘OK, you’re at the Yost Field House. You’ve stolen some IDs.’ This is how Legs framed it. ‘You’re 14 years old, and you see Jim Morrison come onstage. How do you feel?’ I don’t think many people have framed questions like that. That’s why we wanted to do him at the very end, so we totally knew what we were talking about.”

McNeil went on to co-write another oral history book, 2005’s The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry. But for that one, he worked with Jennifer Osborne and Peter Pavia. He and McCain didn’t work together again until they co-edited Dear Nobody: The Real Life Diary of Mary Rose, a collection of a teenager’s journal entries that came out last year. They then began work on Sixty-Nine, the Please Kill Me–like oral history of L.A. rock they hope to finish in two years.

McNeil attributes the long gap between their collaborations to the ragged ending of their work on Please Kill Me.

“We were just exhausted,” he says. “And Gillian hated me. Understandably. I think she had a nervous breakdown after. I think working with me sent her over the edge.”

But she did come around.

“Well, yeah,” says McNeil, “but after 20 years.” She forgot the hard parts, he says.

And now, on the new book? McNeil laughs. “I reminded her.”