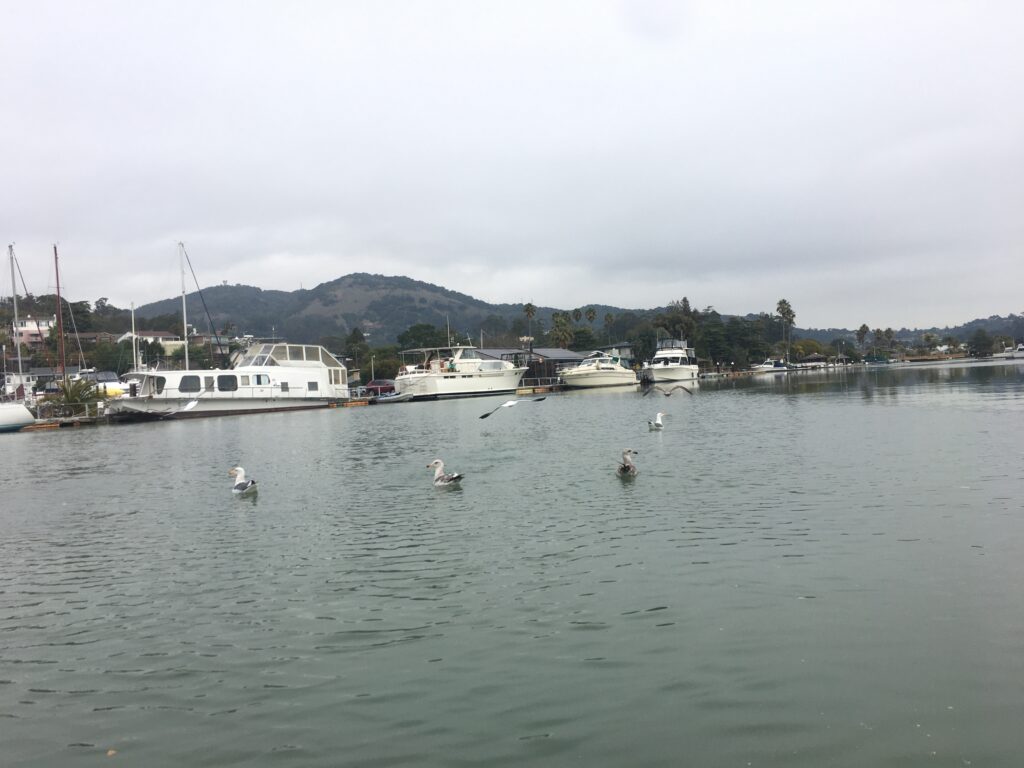

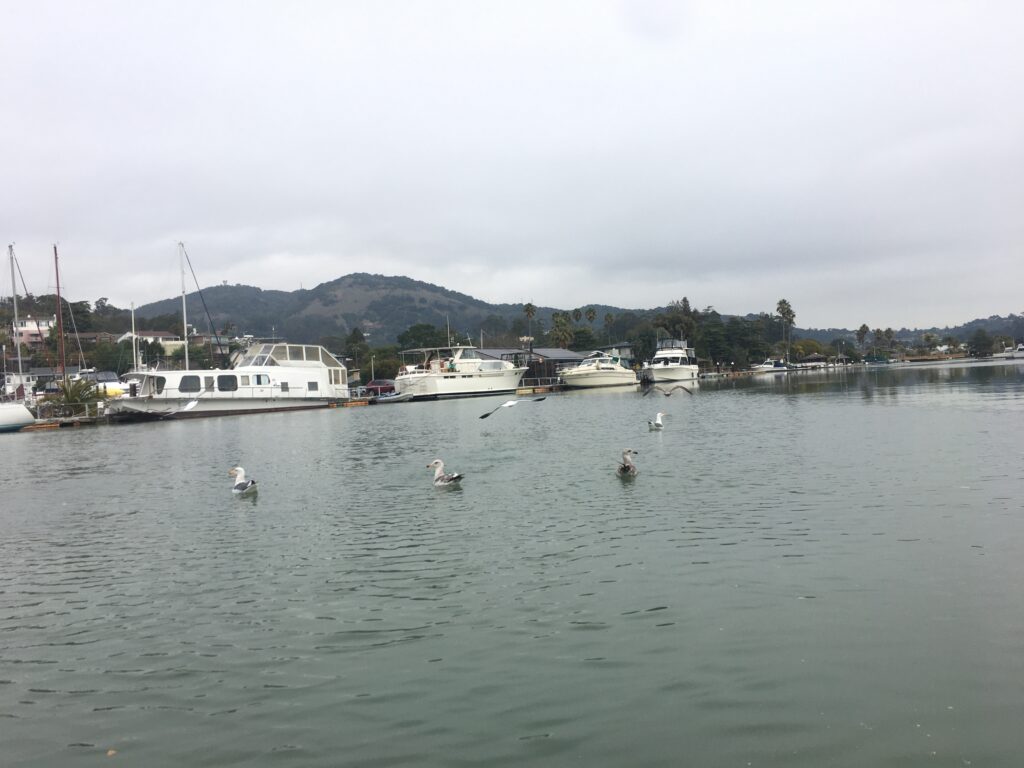

The air was still in early January when my father and I took his kayak onto the waters of San Rafael’s Canal neighborhood. Thin layers of oil floated on the water. Occasionally a plastic bottle or tennis ball bobbed by.

The sky was overcast, a drab blue-gray that nearly matched the color of the three-story apartment complex protruding out into the waters. Though it was cloudy, it was unseasonably warm and humid. It didn’t feel like a normal January day in San Rafael.

As we paddled between ducks, watching people walk around Pickleweed Park along the edge of the water, I imagined what this place might look like in 30 years. It was easy to see how a small rise in the sea could impact this community. All it would take is one big storm.

In the 1870s, tidelands in Marin County were auctioned off to developers. Over the course of more than a century, many of those plots were filled in to create space for new city infrastructure and other developments.

This scenario was not uncommon in the Bay Area. According to Baykeeper, a nonprofit focused on protecting the San Francisco Bay from pollution, 90 percent of all Bay Area wetlands have been “lost or seriously degraded” after being dyked and used for developments. However, due to rising oceans, the dykeing of wetlands now seriously threatens many wild and urban spaces across the region.

San Rafael’s Canal neighborhood is one such place; a small, yet populous, neighborhood located east of downtown where most households are low-income, and 85 percent of residents are Latinx. Built as a navigable waterway in the early 1900s, it is now mostly used for kayakers and other recreational boaters.

It is here where conservationists, community advocates and civil servants are working together to find solutions to the growing issue of sea level rise. And while this is a global issue, there is “little to no federal guidance” for addressing climate issues, the Brookings Institute recently noted. This lack of centralized guidance has left cities and states to lead the way when it comes to adapting to climate change.

In California, where there is some guidance on sea level rise, the state could improve its efforts by providing more funding for adaptation projects and by more effectively sharing critical information with the public, according to a 2019 report by the California Legislature’s Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Marin County and San Rafael have already published sea level rise assessments in an effort to make the risks apparent to its communities.

Now, San Rafael is beginning to consider how to mitigate the worst effects of sea level rise, much of it written out in a new General Plan released in October of 2020. While San Rafael takes this issue seriously, the city is still in the early stages of grappling with how to adapt to sea level rise, which is expected to exacerbate pre-existing inequities, such as housing, in the Canal. A concerted effort is crucial to finding equitable solutions, making the need for a better informed and more engaged public essential to creating progress on this issue.

According to the general plan, sea levels are projected to rise around 4.5 feet by 2100. This would mean that, if nothing is done to adapt, the Canal neighborhood, which sits about three feet above sea level, will be completely underwater, with high tides inundating Highways 101 and 580 to the south. This also means the San Rafael Bay would reach downtown San Rafael, a mile inland from Pickleweed Park. Not only will sea level rise impact the Canal neighborhood—which already faces a housing crisis due to an increasing population and less accessibility to low-income housing—it could also damage many other vital pieces of infrastructure, such as San Pedro Road, one of the city’s emergency exits at the mouth of San Rafael Creek.

The plan proposes many different options for how to combat the potential risk—including elevating buildings, “hard armoring” through the use of levees, restoring marshlands or even abandoning the entire Canal neighborhood. And while simply building a large levee may seem like a solution, the issue is not that simple.

“You can’t really do the job of protecting the dry land from the wet with just a wall or levee,” said Kristina Hill, a UC Berkeley professor of landscape architecture and environmental planning. As the oceans rise, so will the groundwater, creating many issues for sewer systems and other underground utilities, Hill explained.

“Groundwater is rising on top of the sea,” Hill said. “It’s like you’re pushing it up from below.” As Cory Bytof, the sustainability director for San Rafael, said, this is an ever-shifting problem. “It’s just going to get worse and worse over time.”

While many in San Rafael are committed to addressing this issue, the general plan is not binding.

“These documents are not directives, but are guidance,” said Paul Jensen, San Rafael’s community development director, in a town hall in October of last year. “It is going to involve the community.”

The general plan, a state requirement for all municipalities, is developed as a 20-year framework in order to address issues as they arise, this being the main reason why it is non-binding. While some see this as a way of avoiding many issues, it is difficult to find anyone in the San Rafael government who is not concerned with sea level rise.

Kate Colin, the Mayor of San Rafael, said the most difficult part of this issue is helping San Rafael’s general public understand the severity of sea level rise. “People really need to understand the issues, and that alone—starting to understand the magnitude of it—is really a challenge,” she said.

While many who live in the Canal are aware of this issue, higher rates of poverty, along with lower property ownership and a lower English proficiency in the Canal neighborhood, also impact the ability for residents there to be as civically engaged as wealthier residents.

“There has been a lot of data collected that says that these communities are really concerned with climate change,” said Chris Choo, the principal watershed planner for Marin County. “I want us to be careful also that we don’t make the assumption that these communities are not paying attention to this issue. They just have many other things to consider as well.”

According to a study conducted by the American Human Development Project in 2012, “Marin Latinos have median personal earnings just shy of $23,800—less than half those of Marin whites.” This, along with rising rent prices and a growing population, exacerbates the issue of a lack of affordable housing in the Canal neighborhood.

The disparity of wealth is evident when plying the waters of the canal. As my father and I paddled out further toward the Bay, the difference between the north and south sides of the canal became apparent. To the north is the Loch Lomond neighborhood, comprising beautiful suburban and modernist homes with well-maintained docks and pristine gardens tucked beside the hills. To the south is the Canal neighborhood, mostly apartments lining the waterfront alongside palm trees and seemingly forgotten docks. A sunken boat—its sails tucked into its coverings just above the water—lay next to one dock.

“You have poverty in the first place, which is impacting you every single day in different ways, so your priorities are about today,” said Omar Carrera, CEO of the Canal Alliance, an advocacy group for the Canal neighborhood. “Sea level rise, even though it’s an issue today, the conversations are ‘we’re going to be underwater in 2050.’ It’s like, ‘Okay thank you for that, but I need to pay the rent today.’”

In Marin County, the most segregated county in the Bay Area, the Canal neighborhood sits between the need to adapt to sea level rise and the need for affordable housing.

Carrera believes that housing is a more immediate issue and so should be dealt with before, or in conjunction with, the issue of sea level rise. “We need to develop that intersectionality between environment and affordable housing,” Carrera said.

Hill, the UC Berkeley professor, believes risk is a necessary component of combating these issues. “In the Bay Area we’re supposed to be so innovative,” Hill said, “We’re supposed to be wealthy, we’re supposed to be forward-looking—so where are the pilot projects?”

If she could, Colin, San Rafael’s new mayor, would like to see floating homes built, perhaps like ones in Amsterdam. “If we wanted to build, what I would build is floating homes,” she said.

San Rafael does have many innovative options at hand, such as ones created for the Resilient By Design Challenge in the Bay Area in 2018, which gave landscape architects, designers and engineers the ability to conceptualize ideal scenarios of how to mitigate and live with an ever-changing coastal landscape. One design, called Elevate San Rafael, envisioned building more stilted homes in the Canal neighborhood, along with restoring wetlands, in order to create a more hospitable environment both for wildlife and residents. One reason new projects like Elevate San Rafael sometimes do not find funding may be due to a lack of understanding from residents outside the Canal of, as Colin put it, the “magnitude” of the issue of sea level rise.

This was apparent to Colin in 2017, a year after local Bay Area Measure AA—a $12 annual parcel tax—was approved in an effort to tackle sea level rise regionally. This tax raises funds to restore marshlands and maintain “natural protections against future shoreline erosion and sea level rise” through the San Francisco Bay Area Restoration Authority.

In 2017, Colin, then a city council member, along with others, wrote a proposal to receive Measure AA funding to help protect the Canal neighborhood and the Spinnaker Marsh in San Rafael from sea level rise. However, neighboring communities outside the Canal opposed the proposal, in part because one suggested solution in the application of raising a levee. This, they argued, would obstruct home-owner’s views of the bay front.

The city’s 2017 application for Measure AA funding was rejected. In 2019, when San Rafael reapplied for the same funding, the review committee noted a lack of community support for the project as a major factor in its decision to reject the application again. The committee also raised concerns about the project using private land, the protected site not being very large, and the project not reducing “any area in the disadvantaged Canal Community from being below the FEMA 100-yr flood elevation requirements”—a key marker for the effectiveness of a sea level rise mitigation project.

“So they basically torpedoed our ability to get the grants, which meant we [couldn’t] plan, which meant we [couldn’t] start moving forward,” said Colin, commenting on the issue, noting that those who opposed the application were wealthier and had more time to engage with the city than their counterparts in the Canal.

However, in some places in the Bay Area, equity is not the first concern with regards to sea level rise.

Petaluma, which will see an impact due to sea level rise in the coming decades, faces two immediate issues of protecting the wetlands and the wastewater treatment facility, where some of its ponds are likely to be inundated with water.

“The risks are really real here for Petaluma,” said Sam Veloz, a climate adaptation director for Point Blue Conservation Science, in a city council meeting last year. Veloz also mentioned that, if nothing is done by the end of this century, many homes in Petaluma could become inundated by rising waters, according to United States Geological Survey data. This will impact Petaluma’s downtown.

In the decades to come, sea level rise may create housing issues in Petaluma, which is why the city plans to find ways to create equitable and sustainable housing.

“Our planning groups from the community and the consultants are going to be grappling with [the question] ‘where do we put housing that is equitable and resilient from climate change?’” said Gina Petnic, assistant director of public works for the city of Petaluma.

According to Petaluma Mayor Teresa Barrett, wetlands along the Petaluma River are among some of the largest in the Bay Area, making them critical for biodiversity and carbon sequestration. Because of this, Petaluma could potentially acquire Measure AA funding to help protect and reintroduce historic marshlands in the area. However, before Petaluma undertakes any such application, it first plans to “get the science behind us,” according to Petnic.

“We are right in the midst of putting applications out for some grant funding to help us do that planning and that modeling and those assessments for vulnerability,” Petnic said. It is important to note that Measure AA funding is only for restoration projects, not for assessments and surveys, Petnic added.

One project in the Canal has already won Measure AA funds. In 2019, the Marin Audubon Society received a $1 million dollar grant to restore the Tiscornia Marsh, just east of Pickleweed Park in the Canal. The 20-acre marsh, having eroded severely over the past two decades, will be restored in order to provide more habitat for animals, specifically the Ridgway’s Rail, a shorebird that lives in wetlands and is currently protected under the Endangered Species Act.

The restoration of the Tiscornia Marsh will not only restore much-needed habitat for wildlife and “offer great joy” to people, but will also bring practical use to the Canal neighborhood, Barbara Salzman, president of Marin Audubon Society, said.

“The plants slow down the water flow [during storm events] and so that means there is less pressure and less power that hits the shoreline, and so it reduces the erosion,” Salzman said, adding that wetlands help take carbon from the atmosphere.

While the Tiscornia Marsh restoration is due to begin this year, there are still many other issues to address as the need for action on sea level rise grows. This is why, as almost every person I spoke with said, public engagement is critical to addressing sea level rise equitably.

“One of the big challenges is trying to work with the community and find opportunities to meet them where they are,” Choo said.

Choo and others working to develop sustainable solutions for the city say they have to look at many options and see which are best for the people that will be directly impacted first. Due to this, the city intends to focus much of its attention on working with the community in order to decide what the best solutions are.

Instead of developing solutions and forcing them onto the communities, “it seems much better to work with the community and develop ideas,” Bytof, San Rafael’s sustainability director, said. While this may seem like a way for the city to not address the issue head on, Bytof, and many others, have an acute awareness that sometimes what city planners believe is best for a community may not be.

“Our typical way of [dealing with issues in the city] is we gather with consultants and professionals and government leaders and come up with plans and ideas,” Bytof said, “and then we go to the community and ask for input. Sometimes that works and sometimes it backfires.”

In order to boost community input, San Rafael is applying for a grant which would fund two people to work and advocate for the Canal neighborhood. These people would then be able to address the needs of the community and help address sea level rise in a way that is understood and accepted by the Canal neighborhood residents, rather than prescribing a solution without proper understanding of what is needed most by the neighborhood.

One place where community engagement has been successful is Marin City, a predominantly Black community next to Highway 101. Tidal flooding affects the highway as well as residential neighborhoods in Marin City. In an effort to combat the problem, the Marin County Board of Supervisors approved a design contract to improve Marin City pond’s drainage system on Tuesday, March 16. The $773,000 contract, which received significant funding from FEMA, will include a community-input process and is expected to be completed by the end of 2022.

While the project has been a testament to community engagement, Choo believes that the state, particularly agencies such as California State Parks and CalTrans, could be more engaged with creating solutions locally. “I think what we really do need in Marin County, and probably many other places, is for the state to help us plan,” Choo said. “I think it would help a lot of us [in local governments] figure out what to do and how we might start planning [between communities].”

Even without direct state support, people from many different groups across the Canal neighborhood, San Rafael and Marin County are coming together to find the best community solutions to this complex issue.

“I think that that’s really unique in the Canal,” Choo said. “I really do value all of these players coming together and saying ‘all these things are really important and we need to find a way to work with them together.’”

These intersectional conversations are critical for arriving at a compromise in addressing the issues at hand. As Colin pointed out, the first step “is figuring out where we are coming together—where are we in alignment—and using that as a foundation for the other more difficult parts of the conversation.”

On the canal, looking at all of the homes and apartment buildings, lush with greenery and lined with palm trees, I had the odd sensation I was in Florida near the Everglades, though I’ve never been there before. While Miami is already dealing with tidal flooding in the streets, the city continues to build in vulnerable areas. From my vantage point in the canal, where the waters already come within a foot of the land, it was not difficult to imagine a similar situation playing out in San Rafael.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Paragraphs 29 and 30 have been updated to provide more information about why San Rafael’s 2017 and 2019 applications for Measure AA funds were rejected.]