by David Templeton

“It’s an American tragedy, plain and simple.”

On opening night of the Mill Valley Film Festival, director Tom McCarthy peers, spotlight-blinded, into the audience at the crammed-to-the-limit Cinéarts Sequoia theater, in Mill Valley. The audience has just watched a special advance screening of McCarthy’s Spotlight, a riveting, expertly crafted drama about The Boston Globe reporters who cracked the case in 2001, shining a different kind of spotlight onto the Catholic Church’s now infamous cover-up of 70 Boston priests accused, in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, of serial child molestation and other abuses.

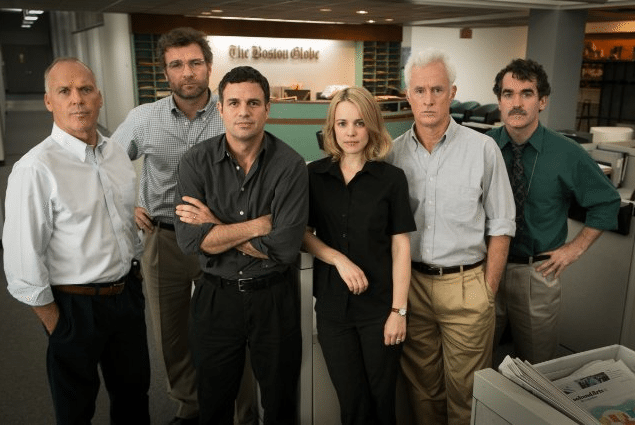

The film features bravura performances by Mark Ruffalo, Michael Keaton, Rachel McAdams, Liev Schreiber, Stanley Tucci and Billy Crudup. With Spotlight, McCarthy—who premiered his critically acclaimed The Station Agent at the festival in 2003—beautifully rebounds from the mega-disaster of last year’s The Cobbler, an Adam Sandler comedy so badly calibrated it made people wonder why McCarthy wanted anything to do with it.

Judging from the audience’s emotional, thunderous reception to Spotlight, all is clearly forgiven, and over the course of a quick, 10-minute conversation after the film, it’s clear that the film will be sparking similar conversations all over the country when it is released to the public in mid-November.

Astonishingly, the most emotional part of the film isn’t the glaring fact that an institution created to spread messages of love and salvation has been institutionally protecting child-abusers for decades. What prompts the first comment from the audience was the movie’s vivid recreation of The Boston Globe in 2001—a newspaper fully staffed and bustling with energy—standing as a cinematic ghost of what journalism in America was not so long ago.

“This movie is a love letter to journalism, definitely,” says McCarthy, pacing slightly as he speaks into a travelling microphone. “For both my co-writer Josh Singer and I, there was something about the journalism hook of the story that just grabbed us. We dug in and spent time with these actual reporters, and realized the depth of the work they did, and the support they had, from their newspaper, back in 2001. When the bottom

fell out of the newspaper industry in 2006, journalism was pretty much decimated. This kind of high-end, local investigative journalism doesn’t happen so much anymore. It still does in some places. There are still great reporters working out there, but they aren’t supported the way they once were, and that’s a real tragedy.

“I didn’t set out, honestly, to write and make a movie that was a love letter to journalism,” he allows with a shrug, “but it just turned out that way, because the work of these reporters was just so thorough and so complete, and so fearless.”

Moderator Mark Fishkin, founder and executive director of the 38-year-old festival, tosses out his own question, asking McCarthy to elaborate on his observations about the decline of American journalism.

“Look,” he says, softly, “I’ve heard from more than a few journalists, including a few tonight, who say, ‘Wow! Those scenes in the newspaper, that’s how it was—and it’s just not that way anymore.” I truly think we don’t realize what we’ve lost. Most of us in this room are concerned about what’s going on in the world, but we don’t have time to go snooping around police stations and colleges and high schools and churches, knocking on doors and talking to people to get the full story. We have always relied on good journalists to get those stories, to find out the truth for us. If they don’t, who will?”

From a woman in the balcony comes a question about the Pope’s recent visit to the United States.

“I really loved this movie,” she says, “and I’m curious if you thought about releasing this film while he was here, so he’d have the opportunity to see it?”

“Strangely enough, the Vatican did request a private screening of the film,” replies McCarthy, quickly adding, “but … no, I’m kidding! That didn’t happen!”

For a second there, though, the audience clearly believed him, and gasped aloud when McCarthy confessed that he was joking.

“It’s amazing that you guys all went with that,” he says with a laugh. “But no, we did not try to get the Pope to see the movie, though we of course knew he was in the U.S. I will say that the organizations that are working so hard on this issue—the members of SNAP [The Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests] and Bishop Accountability, and all those other wonderful organizations that support survivors of clergy abuse—they feel like, with all the goodwill created by this Pope, there’s a possibility of change. I personally believe he is very forward thinking, and that’s exciting and positive, but I still think it just feels like a lot of nice words.

“Until there’s an actual change we can see, then it’s not enough. There are still a lot of children whose safety [and] well-being are at risk. It’s as simple as that. There are still kids who are vulnerable, and the church hasn’t really changed anything. Until they do, nice words are not enough.”

“What should they change?” comes a question from the front row.

“Well, they can start by treating priests the way we treat civilians,” he says. “If you are a pedophile, and you are accused and convicted, you go to jail. Full stop. It’s as simple as that. But that doesn’t happen in the church, or it doesn’t happen often enough. The church protects these priests, and moves them from one place where they’ve been caught, to another place where I guess they hope they’ll just magically be different people. The church is a massive institution, and these practices of protection and denial are ingrained, and nothing is going to change overnight, but we have to start somewhere—and a good place to start is by demanding that criminals, when caught, are treated like criminals. And that being a priest is not a magic license to avoid the punishments and actions that they deserve.”

McCarthy praises his ‘amazing’ cast, after an audience member asks him to elaborate on the actors. In making the film, he says, they all felt a sense of community, urgency and joy.

“That might sound a little weird with a story like this, but there is a real joy you have as a storyteller—whether you are a writer, a director, actor, producer, crew member. There’s just a sense of joy when you get to tell a story that needs to be told.

“This,” McCarthy says, “is definitely that kind of story.”