On a bright, warm August day, I trudged through waist-high grass searching for any trace of the hundreds of graves in a Lucas Valley field.

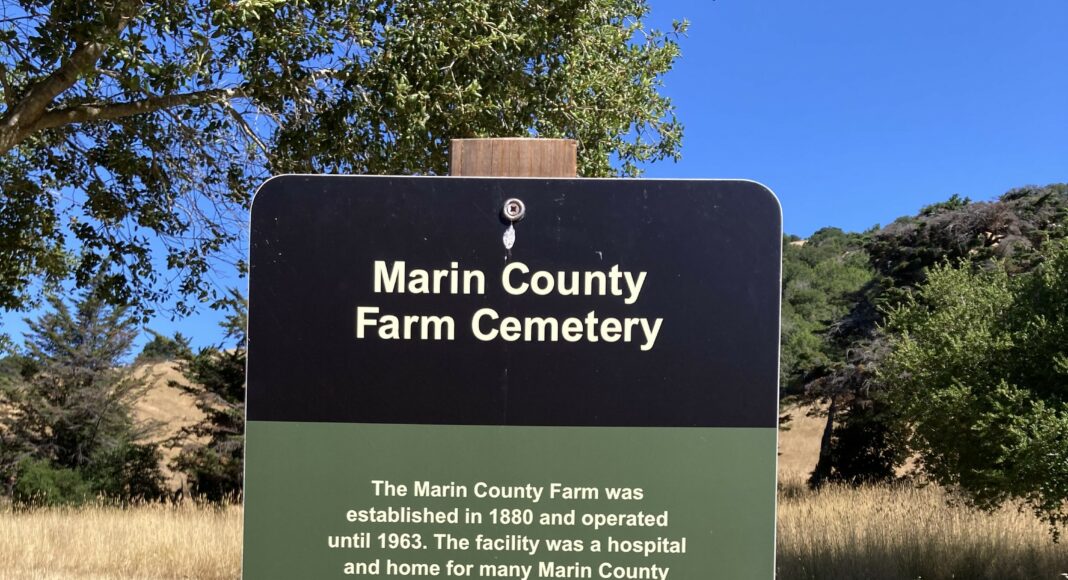

The neglected meadow doesn’t resemble a cemetery—not a mausoleum, a columbarium or even a headstone in sight. I wasn’t sure whether I was in the right area, although a roadside sign indicated that I had entered the site of the “Marin County Farm Cemetery,” where approximately 600 indigent people were buried from 1880 through 1955.

A park ranger had informed me that most of the dead rest in unmarked graves. Since several markers still exist, I kept my eyes cast downward.

After about 10 minutes, I stumbled upon the first marker under an oak tree growing near the middle of the field. The makeshift headstone consisted of a rectangular metal tag, just a few inches long, affixed to a piece of concrete with two tiny screws. The concrete had been poured into a coffee can, which was then embedded in the ground.

Inadequate. Undignified. Almost invisible.

Here lies 72. The number was engraved into the oxidized metal.

Nikki Silverstein.

A few feet away, I found 96. Farther out in the field, 165.

I stopped to honor the unidentified people buried beneath my hiking boots, yet I didn’t know their names—or if they were men, women or children.

The cemetery, on Jeannette Prandi Way, is surrounded by a myriad of buildings. A ranger station, senior housing and the juvenile detention facility also occupy the county property.

I first learned of the Marin County Poor Farm and Cemetery in 2019, when two high school students screened their short documentary, A Silent Legacy, about the site. Georgia Lee and Mitchell Tanaka grew up in Lucas Valley but had no idea people were buried virtually next door—until Tanaka toured the cemetery during the Halloween Graveyard Stroll hosted by rangers from Marin County Parks.

Struck by the need to remember the people interred in the field, most of whom were impoverished, the students began a campaign calling for the county to install a sign at the cemetery. The film, which went on to win several prestigious awards, including the Audience Award for Best Short Documentary at the Golden State Film Festival, bolstered their efforts.

“I wanted to bring reverence to the lost souls that were buried there without any recognition,” Lee told me in an interview. “We had walked and biked past this graveyard our whole lives. Nobody knew it was there.”

The teens’ campaign succeeded. In 2019, Lee, Tanaka and other volunteers built a split-rail wood fence to separate the field from the road. Soon after, a permanent sign was erected to identify the cemetery and acknowledge that a farm, home and hospital also used to stand on the county property in Lucas Valley.

Earlier this month, I was reminded of the Marin County Poor Farm and Cemetery when I attended a lecture hosted by the Mill Valley Public Library and the Mill Valley Historical Society. Mike Warner, who has spent years researching the site, presented a fascinating glimpse into the history and people of what is known as the “poor farm.”

Although Warner is now a supervising park ranger in Palo Alto, he grew up in Novato and was a Marin County Parks open space ranger for more than eight years. In 2016, Warner was one of the rangers leading the Graveyard Stroll, which was loosely based on the poor farm and cemetery. It piqued his interest. Since then, Warner has continued gathering information about the site and sharing its history with the public.

After the Civil War, America went through an economic boom, Warner explained. By the 1870s, a vast expansion of wealth was taking place among society’s top echelon, but working-class people were being squeezed by the rising costs of goods and services. Social welfare became a topic of discussion.

“As we have today, there was a widening gap between those that have a lot of wealth and those that don’t have enough to survive,” Warner said. “Popular political opinion began to swing to say, ‘Hey, we need to take care of our indigent, elderly and sick folks through government support.’”

In 1880, the Marin County Board of Supervisors purchased 94 acres of land in Lucas Valley for $5,717 to establish a poor farm, a place for people who couldn’t afford to live elsewhere. Though the residents were called “inmates,” they were free to come and go.

The farm included cattle, gardens and orchards. Milk and produce were sold to the public and helped feed the farm residents. In 1900, the supervisors passed an ordinance that required residents to work on the farm for their keep; however, the practice stopped in the 1920s or early 1930s.

The first county hospital opened on the property at about the same time as the farm. It consisted of two “pestilence houses” to provide accommodations and care for people with communicable diseases, such as smallpox, typhus, scarlet fever and tuberculosis.

In later years, an addition was built to the hospital, and one of the pestilence houses was converted to a dormitory for 24 nurses. The dorm still stands and is used as a storage facility by the Marin County Board of Education.

The state offset some of the poor farm and hospital expenses by paying the county $100 every six months for each person over the age of 60 admitted to the facility. That’s the equivalent of about $3,245 today.

In January 1881, William Dever’s body was the first to be buried in the cemetery, according to Warner. Dever, notorious for committing robberies and escaping from county jail, died in custody at San Quentin and left no money for his burial.

Occasionally, the death of a poor farm resident was reported in the local newspapers, such as the 1904 account in the Marin County Tocsin of Salvedore Fernandez. “He was a California Indian, and from a reliable source we learn that he was over one hundred years of age. In the year 1824 he appeared at the San Jose Mission and at that time was a full-grown man… And thus a typical Indian, for over 26 years an Inmate of the county farm, a once familiar figure with his trained dogs and sled, passed away.”

In the 1950s, the farm and hospital structures were deemed seismically unsafe. The supervisors chose not to allocate funds to rebuild, and both facilities closed in mid-1963. The remaining few residents and patients were moved to other local convalescent homes and hospitals.

The burial records can be found in the Anne T. Kent Room at the Civic Center branch of the Marin County Free Library. I spent an afternoon going through the delicate files, some handwritten, for Graves 1 through 287. Warner suspects there are far more graves than indicated.

It wasn’t only residents of the poor farm buried there. Stillborn babies, suicide victims and many others who died elsewhere in the county lie in unmarked plots.

Grave 72, one of the three marked tags that I saw, contains the remains of an unknown man hit by an automobile on Highway 101. He was interred on March 3, 1936.

Warner and others are committed to recognizing the people who lived on the farm and are buried in the cemetery.

“I don’t think the intent was to treat them with disrespect,” Warner told me in an interview. “I think it was more of, ‘That’s the best they could do at the time.’”

Perhaps it’s now time for the county to give dignity to those who remain eternally on the grounds by properly marking their graves.

Fascinating stuff. Thanks for your great reporting once again, Nikki.

This was a wonderful article. I had no idea this area existed, and I found myself haunted by the thought that these poor souls had been laid to rest here. This is the kind of article that has real impact for someone my age, 72, and who has lived in the County since 1967 but never knew of this cemetery. Thank you for such a wonderful piece. It is too bad that a large area of land cannot be set aside for the homeless in parts of the Bay Area to work the land and exist simply.

Ive known about this cemetary since the seventies, never researched it though.

A person I know has the “inmate” ledgers from the old juvenile hall , which was destoryed years ago , its interesting.

where can we see A Silent Legacy?

Hi April,

Here’s the link for the documentary: https://vimeo.com/327405805